In recent months, a striking scene has been repeated in media specializing in the technology ecosystem: spectacular announcements about new artificial intelligence (AI) models coexisting with delays in data centers , paralyzed computing-intensive projects , and growing warnings about the physical limits of AI deployment .

Public discourse often attributes these problems to energy consumption or environmental impact. But the source of the bottleneck is more specific and less well-known. The issue isn’t just how much electricity artificial intelligence needs, but how that electricity is managed within the advanced computing systems themselves. And that’s where a discipline that rarely makes headlines, but which determines the true pace of AI, comes into play: power electronics .

Power control

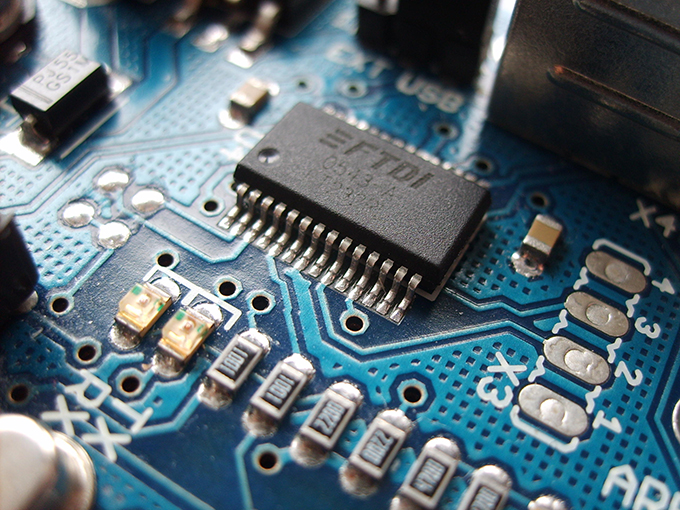

Unlike digital electronics, which processes information, power electronics converts, regulates, and controls the electrical energy that powers processors, accelerators, and high-performance systems. It’s found inside equipment, where electricity must adapt extremely quickly and precisely to loads that change in microseconds. This technology determines whether a system can operate stably or becomes a constant source of losses, heat, and failures.

This aspect has become critical with the current race to increase computing power. The accelerators used to train and run AI models now concentrate unprecedented power densities. Powering them is no longer a trivial problem: it requires systems capable of switching at very high frequencies, responding to abrupt transients—momentary voltage variations—and maintaining electrical stability under extreme conditions . When this conversion fails or becomes inefficient, the problem cannot be solved with more software.

Essential for scaling infrastructure

Much of the recent news about the difficulties in scaling AI infrastructure indirectly points to this phenomenon . There’s talk of supply shortages, data center saturation, and rising costs, but behind many of these headlines lies a specific technical challenge: internal electrical conversion has become a limiting factor in the design .

As power per unit volume increases, the electronics that power the systems go from being just another component to conditioning the entire architecture.

Without energy, there is no AI.

For years, digital progress benefited from continuous improvements in conventional electronics, allowing for increased performance without fundamental system redesign . However, this margin has narrowed. Today, every increase in computing power requires redesigning how energy is delivered, controlled, and how the generated heat is dissipated. In this context, power electronics is no longer a cross-cutting or “support” technology but rather a prerequisite for the most advanced AIs.

This shift explains the growing interest in new power semiconductors , capable of operating at higher frequencies, with less loss and greater density.

This is not an incremental improvement, but a direct response to the physical limitations that are beginning to emerge in intensive computing. The ability to reliably feed an AI system now determines both its viability and the sophistication of the model it runs.

Clash with physical limits

For decades, international technical communities such as the IEEE Power Electronics Society and the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society have been working precisely on this point of friction between advanced computing and physical limitations. Their experience shows that many of today’s AI challenges will not be solved solely with better models, but with advances in the engineering that enables their continuous and safe operation.

Despite all of the above, this dimension barely appears in the public narrative on artificial intelligence, which remains focused almost exclusively on data, algorithms, and cognitive capabilities. AI is presented as an abstract technology when, in reality, it depends on extremely demanding electronic infrastructures. Ignoring this layer leads to unrealistic expectations about the speed at which it can be scaled and deployed in real-world environments.

This does not mean that artificial intelligence is “stuck” or that its development will stop. It means that its actual pace is increasingly constrained by material factors that are rarely discussed outside of specialized circles.

A comprehensive vision

The relevant question is no longer just what an algorithm can do, but what the hardware that powers it can sustain for years, without failing and without skyrocketing costs.

Perhaps that’s why the current debate on AI needs to be broadened. Not to diminish the importance of software, but to incorporate a more comprehensive view of the technological system as a whole. Because the advancement of artificial intelligence doesn’t depend solely on what we are capable of coding, but on what electronics can support stably, efficiently, and reliably. And that limit is now beginning to become apparent.

Author Bio: Paula Lamo is a Professor and researcher at the University of Cantabria