Australia and the UK experience regular annual outrage over vice-chancellors’ pay. This is unsurprising – in Australia their average pay at the 37 public universities topped A$1 million in 2019. Those at prestigious Group of Eight universities were paid more than A$1.2 million on average.

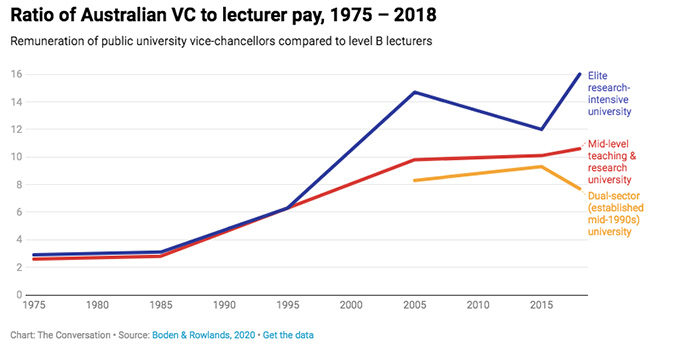

Vice-chancellors’ pay has soared over recent decades (although most accepted pay cuts this year as part of COVID-related savings). In 1975, our research suggests, vice-chancellors at elite Australian research-intensive universities received about 2.9 times the pay of regular lecturers on Level B – the second-lowest and most numerous academic grade. By 2018 they were earning 16 times as much.

Source: Boden & Rowlands, 2020 Get the data

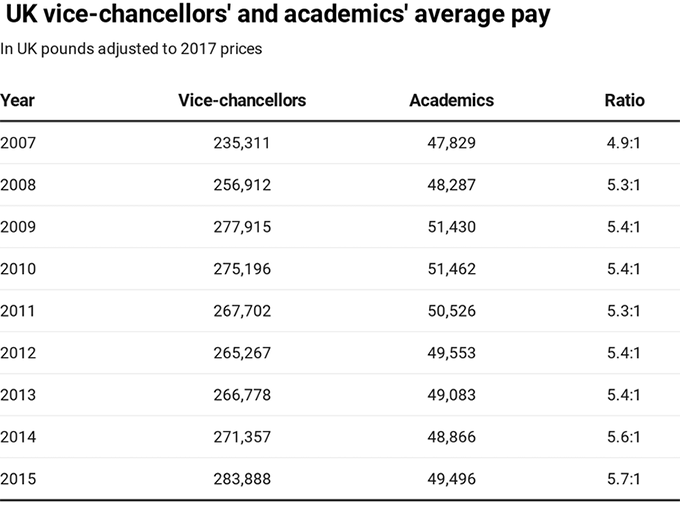

Similar, but less extreme, trends are evident in the UK. In 2018-19 vice-chancellors received nearly £350,000 (A$635,000) on average.

Figures are just starting to be published showing the ratio of VC-to-staff average pay at each UK institution. Of the 20 highest-paid vice-chancellors in 2017-18, London Business School had the highest ratio at 12.8 times average staff pay, with the 20th-placed University of Reading having a ratio of 9.2.

Source: Boden & Rowlands (2020). Adapted from Gschwandtner and McManus (2018), Author provided

These trends prompt questions about what is going on. Universities are public institutions funded primarily by fee-paying students and taxpayers. As such, it is important to consider whether students and the public are getting value for money from these salaries. If not, we need to understand how salaries have been inflated and find ways to keep them in check.

When universities are challenged about these salary packages, they say vice-chancellors run complex “businesses” in competitive global markets, and their salaries reflect the work done and results achieved. Of course, these are demanding roles, but econometric research demonstrates little, if any, relationship between vice-chancellors’ pay and their actual performance.

An exception to the rule, Australian National University’s Brian Schmidt is a Nobel laureate and vice-chancellor of one of the country’s most prestigious universities, but was the second-lowest-paid on about $650,000 in 2019. Mick Tsikas/AAP

What is driving these increases?

Econometricians also looked at what might be driving these pay hikes. They concluded that benchmarking and salary tournaments play a role.

Benchmarking is a technical exercise whereby universities pick comparator organisations and pitch senior staff salaries at similar levels. This tends to generate a race to the top – pay rises in one university ripple through the others.

In salary tournaments, pay levels reflect the hierarchy of organisational roles. So, if universities hire highly paid marketing or communications staff, it drives up pay levels for those above (but not below) them.

An issue of governance

Benchmarking and pay tournaments explain the mechanics of how this is happening, but not why salary resources are allocated in this way. To unpick that, we explored the governance structures of universities.

Over the past 30 years, Australian and British universities have been marketised, emulating private-sector for-profit organisations. Core to that process has been the transition of vice-chancellors from being “first among equals” in academic communities to entrepreneurial chief executive officers of quasi-corporations.

In real market businesses, CEOs hold a lot of power, including the power to enrich themselves at the cost of the dividends paid to shareholders. In the dominant agency form of governance used in business, shareholders are cast as principals and executives as their agents.

Shareholders try to assert control by rewarding executives through salaries related to performance, creating an alignment of financial interests. Executives get paid more than their work is worth, but less than the cost shareholders would incur in more closely monitoring them – and executives are freed up to act entrepreneurially.

Problematically, universities are quasi-market not-for-profit organisations. As such, they don’t have controlling owners/shareholders. They do have governing councils, which are legally recognised as principals.

The problem is council members don’t have the same financial self-interest as shareholders – the vice-chancellor’s pay does not reduce their own profits. They might even prefer to pay their vice-chancellor over the odds because it makes their university look more prestigious. It also makes it less likely they’ll leave, saving them the bother of appointing a new one.

What can be done about the problem?

Governments could act as de facto principals because universities are public bodies of which they control the purse strings. But, in Australia and the UK, governments have opted for a hands-off approach, urging universities to behave like free-market organisations and not “interfering” in their internal affairs.

It hasn’t always been like this. From 1976 to 1986, the Australian government set recommended maximum salaries for vice-chancellors. Universities were penalised financially if these guidelines were breached.

This approach was abandoned as marketisation set in. Salaries have skyrocketed since.

As a result of this flawed governance framework, universities usually allow vice-chancellors to be members of, or at least attend, the remuneration committees that set their pay. When challenged, they maintain the vice-chancellor “leaves the room” when their pay is decided. The corporate world would not tolerate such practices.

It’s clear there is a governance dynamic that is driving the pay escalation. And when salaries are not justifiable by performance, they can be said to constitute rent – an economic concept that means extracting an unjustified level of resource from an organisation as a result of ownership or control.

Publicity around increased disclosure has so far done little to rein in salary increases.

Government being a proactive principal worked before in Australia. This suggests governments could, for instance, require maximum fixed ratios between vice-chancellors’ remuneration and average academic salaries. This would require considerable political will, but there is little evidence of an appetite for that.

Author Bios: Julie Rowlands is Associate Professor in Education Leadership at Deakin University and Rebecca Boden is Chair Professor, New Social Research at Tampere University