As college football bowl and playoff games unfold before a TV audience of millions, most of the attention will be on the final scores. Less is likely to be said about certain bonuses that the coaches get for their bowl and playoff appearances.

For instance, when the Fresno State Bulldogs defeated Arizona State in the Las Vegas Bowl on Dec. 15, the Bulldogs’ coach, Jeff Tedford, already being paid US$1.6 million per yearthrough 2021, got a $200,000 bonus for the win. He would have gotten $100,000 even if his team had lost.

Western Michigan’s Tim Lester gets $25,000 for making it to the Famous Idaho Potato Bowl on Dec. 21.

Since college football coaches are already often the highest-paid public employees in their state – their eye-popping salaries often dwarfing even those of state governors – it may seem strange that coaches could collect bonuses that surpass most families’ annual income, on top of it all.

It may also be tempting to think of the bonuses as being a byproduct of lucrative marketing deals that colleges started to get in the 1980s and television contracts that they started to get in the 1990s. But history shows that bonuses for college football coaches stretch back to the early 1900s, well before the invention of television or even the first commercial radio broadcast.

These bonuses create a market for winning that fuels the business of college sports. In my view as a scholar who studies big-time college football, these bonuses are not a reaction to a multi-billion-dollar market that rewards winning – they are the foundation of it.

Bonuses go back to early 1900s

The first superstar college football coach contract on record to include compensation beyond base salary was signed by the legendary John Heisman – for whom the coveted Heisman Trophy is named – to coach Georgia Tech’s football team in 1904.

Records show that Heisman’s contract added 30 percent of all ticket sales to his annual $2,500, a salary that would have been the equivalent of just under $71,000 in 2018 dollars

Heisman’s contract was an acknowledgment that the football coach was uniquely intertwined with revenue generated during games. But it was also notable, as coaches’ salaries were then often decided based on the relationship to faculty and administrator salaries. Ewald Stiehm, University of Nebraska head football coach from 1911 to 1915, was famously denied a $750 raise by the school because they didn’t want a coach making more than the top professor. His salary at Nebraska was $4,250. He went to Indiana, which paid him $4,500.

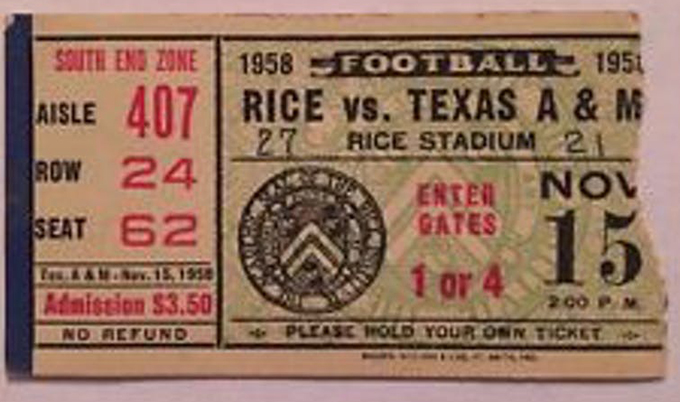

Before television deals and marketing contracts, high salaries and added incentives were reserved for those top-tier coaches deemed capable of bringing a “winning culture” to the institution. Bear Bryant’s 1954 contract was one of the few before 1980 to rival Heisman’s. It included 1 percent of Texas A&M football ticket sales. Tickets in 1958 went for $3.50 per ticket.

1958 Texas A&M ticket stub.

Million-dollar men

The first million-dollar contract was signed by Bobby Bowden with Florida State University in 1995. Bowden only had one losing season in his 34 years at FSU and was coming off a 1993 National Championship when his contract was extended with a $300,000 per year raise, including another $700,000 in television appearance and apparel promotion bonuses. For the first time, pay was tied not just to winning – but to winning enough and in the right way. Exponential increases in revenue generated via ticket and apparel sales, bowl appearance payouts and even application pools beyond student athletes, are evidence of the value of wins – first culturally to university communities, then economically for universities’ financial health.

A bonus bonanza

Today a long list of bonuses are included in contract offers to top coaches as additional compensation for winning.

Beyond incentives like home loans, car allowances and country club memberships, merit bonuses attached to bowl appearances, win-loss records, divisional rankings and national championships emphasize the value of coaches to their institutions. Some bonuses have little to do with the game’s final score – like UConn’s Randy Edsell earning a $2,000 bonus every time his football team scores first or leads at halftime.

The bonus money coaches are paid in exchange for those highly valued wins is a small fraction of what the institution earns for those wins. National tournament qualification and bowl appearances trigger additional bonuses, not only because they excite the fans but because they mean more revenue for the institution. Merit bonuses are a small price to pay to keep money flowing into a university through victories on the field – wins.

Cashing in

In my opinion, coaches aren’t taking advantage of universities under this scheme. The universities are in on the joke. Universities were heavily involved in creating fiscal environments where high salaries and merit bonuses for coaches were more feasible. Bowden’s 1995 contract would’ve been impossible if not for important legal victories led by individual universities seeking to transform college sports to big business.

For instance, the 1984 Supreme Court ruling in NCAA v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma found in favor of individual universities negotiating television contracts directly with major networks. The ruling described the NCAA’s control as in violation of anti-trust law. The move forever changed the financial landscape of college football and basketball, and introduced an influx of cash into the market.

The 1984 ruling meant schools and division conferences, like the Southeastern Conference, of which schools are members, could negotiate deals independent of the NCAA. The resulting influx of money into college football is directly connected to today’s high coaches salaries. In 2017, when the Big Ten’s new television deals with cable news networks ESPN and Fox kicked in, the conference was also home to five of the top 14 highest paid football coaches in the NCAA.

The win-first mentality

“Winning cultures” also encourage student athletes to buy into win-first, team-first thinking. This can be dangerous because it encourages coaches to push players beyond their limits. Earlier this year, University of Maryland football player Jordan McKnight’s death uncovereda record of dangerous workouts driven by then-head coach DJ Durkin and the university leadership’s desire for wins and a stronger financial future.

The power given to coaches with winning records is not new. They are the foundation of college football. Before players or fans, there are coaches. As long as millions of people continue to enjoy college football games and attach so much meaning to the final score, football coaches will continue to fatten their pockets as a result.

Author Bio: Jasmine Harris is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Ursinus College