To the untrained eye, the small community garden on Coast and Straits Salish territory — on what passersby commonly know as the University of Victoria campus — might look unruly. Bursting with dandelions, lamb’s ear and grasses, it’s difficult to tell where the garden starts and where it ends.

Wondering where those boundaries begin and end has been a fruitful challenge for children, educators and researchers at the University of Victoria child-care centre who now work in the garden.

The group buried itself in the garden overgrowth with gusto, rather than manage it. They didn’t know what was growing there or how. Those unknowns allowed them to move beyond the idea of a “controlled garden plot.” Instead, they think about what belongs and why, to consider what else they do not know.

Such approaches are critical for children of this generation, and of generations to come, who are inheriting an ecologically precarious world.

Climate Action Childhood Network

The educators with the University of Victoria centre, along with educators from more than 10 collaborating early childhood centres in five countries (Australia, Ecuador, Canada, United States and United Kingdom), are part of the Climate Action Childhood Network.

As the director of this network, which is composed of international interdisciplinary researchers and practitioners, I see the importance of generating responses to climate change through creating and experimenting alongside young children. Educators develop climate-specific experiences with children in different early childhood centres to address topics such as relationships with food, animals, energy, weather, waste and water.

Some of the environmental conditions that young children face today are toxicity, extraction, destruction, drought, pollution, wildfires and extreme weather. Yet, children are rarely consulted or included in environmental decisions.

We believe a paradigm shift in early childhood education can provide a path to deeper societal changes that are required. The shift means moving from learning that is information-driven to learning that is situated, speculative and experimental.

Collaborate with garden inhabitants

It can begin with something like the community garden on Vancouver Island, led by researchers B. Denise Hodgins and Narda Nelson, that challenges ideas around managing and stewardship. There, the children are learning to collaborate with the community garden’s inhabitants: by planting, digging, fertilizing, watering and responding to the garden’s own actions.

Prior to working with children to cultivate an awareness of Lekwungen food systems — a system of relations that predates settler colonial garden practices on these lands — educators attended a Colonial Reality Tour led by Cheryl Bryce. Bryce is from the Songhees Nation, traditionally known as Lekwungen. The educators also engaged in dialogue with with Earl Claxton Jr., a SȾÁ,UTW̱ (Tsawout) W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich) Elder, ethnobotanist and Knowledge Keeper.

Challenging assumptions

When educators invite children’s speculations, we can tap into other worlds that allow us to imagine alternatives.

“These beans are going to grow so high they will reach the clouds!” one child said on a recent visit to the garden. This is a beautiful declaration that forces us to challenge our assumptions.

The Climate Action Childhood Network, alongside the Common Worlds Research Collective, positions early childhood education as a collective practice of “learning with” others. The goal is to move beyond learning “about” the climate crisis to seeing ourselves as part of it.

The goal is to move beyond learning about the climate crisis, to seeing ourselves as part of it. (Narda Nelson), Author provided (no reuse)

One example is Conversations with Rain, a project in Western Australia between the Art Gallery of Western Australia and researchers Mindy Blaise and Jo Pollitt.

They worked alongside young children to respond to a painting, Raining on Kurtal, by Wangkatjunga/Walmajarri artist Ngarralja Tommy May. Children were invited to think with their own breathing. In a sketchbook, children began by marking a line for every inhale and exhale until a page was full. Then, considering the question “What if raining is writing?” children wrote as fast as rain, without stopping or planning.

Water stories

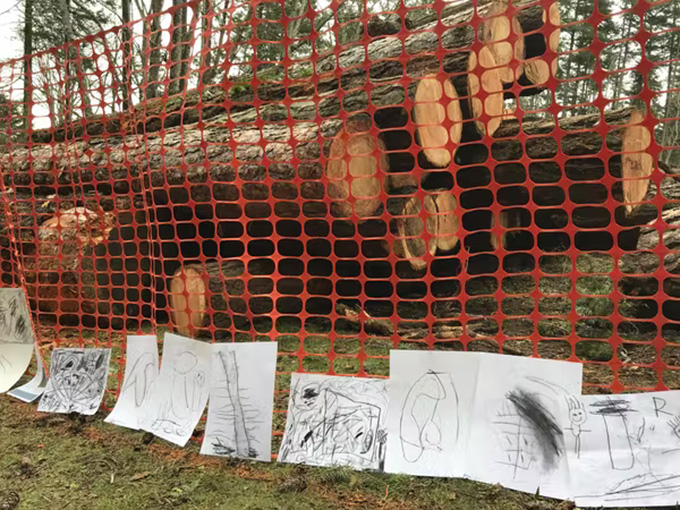

Another project involved children, educators and researchers exploring creeks in each other’s environments across the planet. A group participated from Criuckshank Park, in Wurundjeri country in Melbourne, Australia — once a grassland, then a bluestone quarry that polluted a creek and now a greenbelt that winds through a gentrifying suburb. Another group was located in Haro Woods, an urban second-growth forest on Canada’s West Coast on the unceded, traditional and ancestral lands of the Coast and Straits Salish peoples, and what is known now as Victoria.

Researchers Nicole Land and Catherine Hamm, working alongside children in their respective creekside settings in Australia and Canada, used FaceTime to explore new ways to connect. Sitting creekside, children and educators used FaceTime to share creek and water stories with one another. They listened to the sounds, asking: Where does the water go when it runs dry during certain seasons? What stories did this place tell before settler colonialism?

Educators with children listened to the sounds of creeks. (Fikile Nxumalo), Author provided (no reuse)

“Our water stories are not worried about saving or rescuing the water,” the project collaborators wrote. “Rather, they are about what might be required to carefully stay with the troubles made visible with polluted creeks in urban nature spaces.”

The point of the FaceTime project was not to reinforce the idea of children as “global citizens” who should learn about people and practices in other cultures and places.

In fact, it resisted that urge to exchange facts about the parklands. Instead, it was concerned with what feminist scholar Donna Haraway described as “passing patterns back and forth”. Haraway discusses the children’s string game of cat’s cradle that can be passed (and elaborated) from person to person as a metaphor: When we “hold” each other’s stories and creations, this collective attention opens up new possibilities.

Pandemic experiments

Our work responded to the pandemic, too. A project based out of Cuenca, Ecuador, turned the difficulty of lockdown into an opportunity to experiment with an itinerant school.

Educators at Santana’s Children’s School with researchers Cristina D. Vintimilla and Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw created home gardens across the city. Children met with teachers three times weekly to create a curriculum that responded to the specific surroundings.

In an itinerant school on Cabogana Mountain, one child noticed how a particular stick looked like the leg of a hen wandering the garden. This triggered an exploration of the bird’s movement through imitation and drawings.

The Climate Action Childhood Network has created new modes of engagement in environmental early childhood education. These modes will create the conditions for society’s youngest members, who will be the most impacted by ecological challenges in the long term, to actively participate in transforming the world they are inheriting.

Author Bio: Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw is Professor of Early Childhood Education at Western University