On September 18, 2020, a column published in Marianne signed by 32 linguists took a clear position against inclusive writing or, more exactly, against the use of abbreviated spellings (for example: students). This forum was presented as an objective clarification denouncing a practice which, according to its signatories, “is free from scientific facts”.

The reactions were not long in coming. On September 25, 2020, a forum signed by 65 linguists took the opposite view of the first, while at the same time appeared a text signed by Éliane Viennot and Raphaël Haddad and various critical analyzes . This controversy might seem anecdotal. In fact, we can draw some interesting lessons on languages and how they work, as well as on the use of expert scientific discourse to found prescriptive discourse (“we must… we must not…”).

Some historical milestones

30 years ago, in France, a movement led to the feminization of the names of functions, professions, titles and ranks. Very quickly relayed by political authorities, it aimed to “legitimize the social functions and professions performed by women” (Decree of February 29, 1984). He succeeded in imposing, in the uses and even under the dome of the French Academy (declaration of February 28, 2019), the use of feminine forms which were sometimes created (an engineer, a firefighter), sometimes rehabilitated (an author, an officer) or sometimes simply more widely distributed (the president, the senator).

This awareness has made it possible to develop the French language so as to meet the needs of people who speak French. The difficulty that Francophones face today concerns the (good) ways of using these female names in all areas of life: administration, education, politics, artistic creation, business, daily life, etc. Inclusive writing no longer designates feminization, but the use of these feminine names alongside masculine names in texts.

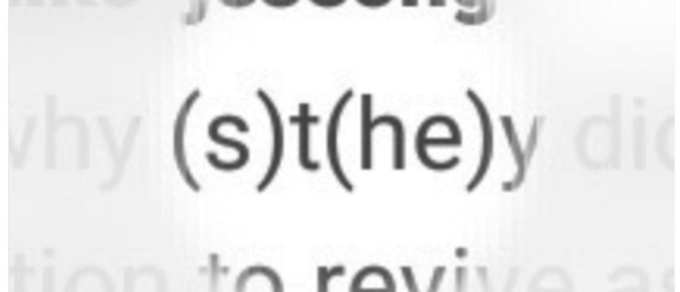

Inclusive writing, also known as epicene writing (in Switzerland and Canada), non-sexist writing or egalitarian writing, represents a set of techniques that aim to bring out equality, or symmetry, between women and men in texts. and to adopt a language which does not discriminate against women. We choose here to consider inclusive writing without non-gendered writing, also called neutral or non-binary, which pursues an objective of inclusion of course, but also very specific: not to choose between the feminine and the masculine and not to categorize people according to their gender.

Rules that are (almost) not controversial

Some rules of inclusive writing are widely accepted and appear in all guides. There are virtually no differences regarding the following:

(1) Use feminine names to designate women in their function, profession, title or rank: say “Madam President” and not “Madam President”, “the surgeon” and not “the surgeon”, “the officer of the Legion of Honor ”and not“ the officer of the Legion of Honor ”. Note that some names, despite known roots, are not yet welcomed without restraint (for example: author or professor).

(2) Use the expression “women” as soon as you designate a group of women and reserve the expression “the woman” (or “the Woman”) to refer to a stereotype: say “the international day of human rights. women ”or“ the situation of women in Algeria ”; but to say “this actress embodies the femme fatale”.

(3) Use “human, human” rather than “man” to denote a human person, as in “human rights”, “human evolution”.

(4) Always use the term “Madam” when addressing a woman (as the feminine counterpart of “Monsieur” when addressing a man) and no longer use “Mademoiselle”, which creates an asymmetry, since “Mondamoiseau” is rarely used.

(5) Do not name a woman after the office or title of her husband: say “the ambassador’s wife” and not “the ambassador”.

(6) Use the proper names of women as one uses those of men. Do not use a woman’s first name when using a man’s last name, for example in a political debate (do not say “Ségolène against Sarkozy” or “Ségo against Sarko”). Do the same for the common names (do not say “Fed Cup girls” and “Davis Cup men”).

Rules that spark controversy

Other rules still cause controversy (in France and Belgium in particular), because they create ways of writing or speaking that seem unusual. The arguments invoked to defend or to reject these rules come from the history of language, linguistics, sociology or the psychology of language, and sometimes ideology. However, current studies (a bibliography is available here ) provide us with a scientific perspective that should help us navigate the intricacies of this subject.

(1) Use the masculine to designate a person whose gender you do not know, as in a job offer: “research computer scientist (M / F)”. There is evidence that this rule does not promote fair treatment of women and men. Numerous scientific studies have shown that the use of uniquely masculine terms (“a mathematician, a sales manager, a musician”) engendered masculine mental representations in adults on the one hand, but also in young people. Even if this use is permitted by French grammar, it seems, for example, to influence the professional aspirations of young people. It has as a consequence, in particular, to decrease the degree of confidence of the girls and their feeling of self-efficacy to undertake studies for these trades.). It also gives the impression to young people that men are more likely to succeed in these trades ). In sectors where one seeks to create more diversity, such as science and technology, or nursing, the so-called generic masculine should be avoided.

(2) Use the masculine plural to denote groups that contain women and men, such as “musicians” to denote a mixed group. It is proven that this rule does not favor an interpretation which corresponds to the designated reality. Scientists have shown repeatedly (and in several languages) that, although the grammar allows a “generic” interpretation of the masculine plural, this interpretation is not as accessible or frequent as the specific interpretation (masculine = man). This difference in accessibility was explained by different factors), like the learning of grammatical gender, which invariably follows the same sequence: we learn the specific meaning of the masculine (masculine = man) before its generic meaning. In other words, when we say “the musicians”, the mental representation that is most easily formed is that of a group of men, the specific meaning of the masculine being much easier and quicker to activate. The mental representation of a group of women and men takes longer to train and more difficult to access. The masculine bias induced by the masculine grammatical form has been demonstrated in different contexts and countries ( for example, in France ; in Switzerland ; and recently in Quebec). Quite rare in science, there is, to our knowledge, no data contradicting the automatic dominance of the specific meaning of the masculine.

If one wishes to activate the image of mixed groups, it is preferable to use strategies other than the masculine, such as duplicates: “the surgeons”. Despite these results, some people, sometimes through writing guides, commit to not using duplicates. Different reasons are advanced, often without any real scientific basis. For example, duplicates would hinder reading. To our knowledge, no study supports this idea. There is a study which shows that even if at the first occurrence of a duplicate, reading is slowed down, from the second occurrence, reading becomes completely normal again (habituation effect)). The idea that people who use duplicates would not be able to achieve grammatical agreements in texts is also astonishing, especially if we observe a return of the proximity agreement), a chord particularly suited to the use of duplicates .

On the other hand, scientific studies show that the order chosen to present each element of the pair (“the bakers and the bakers” vs “the bakers and the bakers”) has an effect on the interpretation: the element presented first is seen as more central or more important .

(3) Some people also agree not to use abbreviated forms which make it possible to present duplicates in writing: “students”, “pharmacists”. The current results of scientific research are too limited to comment definitively on this subject. One study ) measured the effect of shorthand duplicates on reading. It concerns a public of students for whom a slight slowdown in reading was measured at the first appearance of these forms, but then normalized. However, we cannot conclude from this study that the effect would be the same, or different, for other populations. And the reasons for the slowing effect, such as the habituation effect, are not yet fully understood.

It has also been shown that presenting trades in a contracted form (at the time with a parenthesis) can increase girls’ confidence and feelings of self-efficacy in undertaking studies for these trades . Research should nevertheless continue to test the effect of these abbreviated forms: according to the typographical sign used (dash, midpoint, etc.); according to audiences of different ages, education levels, socio-economic levels; depending on the types of texts. Only additional research will make it possible to propose better informed rules to regulate the use of these forms, which appeared mainly to respond to the limits of signs imposed in various fields (journalism, Internet, etc.).

(4) Finally, some guides recommend more flexibility in the management of agreements. To the established rule of the generic masculine agreement (“the brother and the sisters have arrived”), they suggest leaving the possibility of applying the proximity agreement (with the closest term: “the brother and the sisters have arrived ”), majority agreement (with the most important element in number:“ the sisters and brother have arrived ”), or an agreement of your choice. The historical argument is often invoked, and rightly so: the proximity agreement is observed in old texts in 45% of cases., but it is still less frequent than the masculine chord. The historical argument does not allow us to claim an exclusive “return” to the proximity agreement, since it has always cohabited with other forms of agreements. It does not allow to exclude it either, since it was important. Research should show what specific problems, in learning, writing or understanding texts, pose these different types of agreements.

The inclusive writing war will not take place

Current scientific knowledge makes it possible to clarify the validity of certain rules which give rise to disagreements. For other rules, yet defended or contested in a very assertive manner, it is necessary to recognize that current knowledge does not yet allow a decision. Research must continue to be done in order to provide arguments for the proposed tools.

The French language is not only the domain of scientists. As scientists, we believe that uses must be allowed to develop because they meet basic communicative and social needs. Not all uses are appropriate for all genres of writing, but the standard should not be overwhelming. Let us also trust francophones.

Author Bios: Christophe Benzitoun is a Lecturer in French linguistics at the University of Lorraine, Anne Catherine Simon is a Professor of French Linguistics at the Catholic University of Louvain and Pascal Gygax is at the University of Friborg