The world of graduate research studies in higher education is not typically deemed cinematic material: the “actions” of scholarship are rather prosaic. However, two films currently in cinemas have put graduate research on the screen.

Sorry, Baby, an indie film by writer/director Victor Eva and Luca Guadagnino’s After the Hunt, from a screenplay by Nora Garrett, connect with the genre and online aesthetic of “Dark Academia” and its obsession for all things scholarly.

It’s popularity online explains, to a degree, why these “PhD films” are of interest to screen audiences of different generations. And both films blend towards a “Grey Academia”, exploring the ethically grey areas of the modern institution.

The world of dark academia

Stories of Dark Academia unfold in the shadows of university cloisters. The characters are university professors and their students. The dress code tweed or preppy.

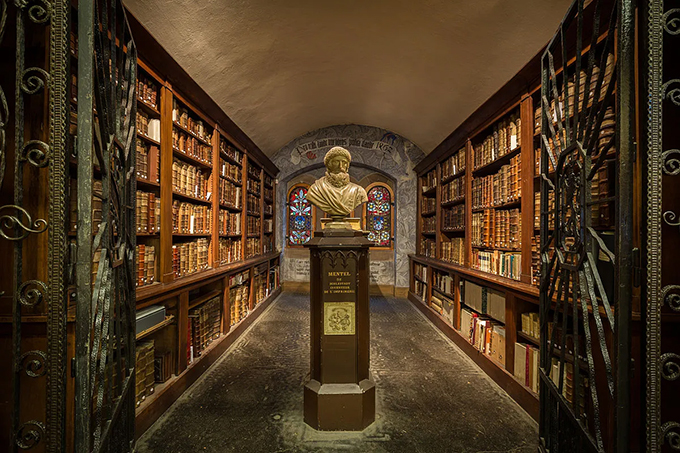

The term is relatively new. It first described an online aesthetic on Tumblr then TikTok, with users sharing idealised images which romanticise higher education, literature and the arts.

@ympjms So, let me offer you immortality… A night wrapped in candlelight, strings, and stillness somewhere between music and magic (Candlelight: Best of Magical Movie Soundtracks) ️ @candlelight.concerts @Fever @SEA LIFE Melbourne ( #ad / #gift) #CandlelightConcerts #sealife #datenight ♬ original sound – Oleen J

The genre is porous. It has been reverse-engineered to revisit the campus novel/film/TV genre, including mainstays such as Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (1945) and Donna Tartt’s The Secret History (1992).

During COVID, Dark Academia proliferated online with students locked out of their universities, pining for the real thing.

Publishing followed: Mona Awad’s Bunny (2019) and R.F.Kuang’s Katabasis (2025) are stories of graduate students in distress. The world of PhD study meets crime, psychosocial harm and sometimes magic and the occult.

The #metoo fallout

Sorry, Baby and After the Hunt share New England campus settings, in the northeastern United States.

The darkness in these films is shaped by incidents, and allegations of, sexual assault. They rely on genre to explore a post #MeToo sensibility: Sorry, Baby is a “traumedy” and After the Hunt a psychodrama that oscillates around, rather than confronts the inciting incident.

The main characters are humanities professors. Sorry, Baby’s Agnes (Eva Victor) is a young, creative writing professor at a regional university who has flashbacks to her trauma as a graduate student. After the Hunt’s Alma (Julia Roberts) is a middle-aged professor of philosophy at Yale, supervising students in ethics.

Both professors are white and privileged. However, the films foreground a queerness and gender fluidity consistent with Dark Academia on social media, as a generational update of the campus genre. They share a muted mise-en-scène but it is Guadagnino’s film in which scenes are (literally) bathed in darkness.

In After the Hunt, Maggie (Ayo Edebiri) is a queer, millennial, black woman (coded Gen-Z at times) who is portrayed to be at best a mediocre student or at worst a plagiarist. Her PhD supervisor and mentor, Alma, struggles with pressures of modern academia: teaching, publishing and campus politics. Her remedies are copious amounts of red wine and (illegal) pain prescription pills.

With tenure just in sight, Maggie files an accusation of sexual assault against Hank (Andrew Garfield) who is Alma’s close colleague and confidante. Generational conflict plays out on the Beinecke Library plaza where Alma calls out Maggie’s “accidental privilege” and performative modes of “discomfort” through a lens of identity politics.

Maggie dresses as Alma in elegant, recessive preppy wear. This tilts towards “Light Academia”, a more optimistic version of the genre which peaked with the highly forgettable Netflix film, My Oxford Year (2025).

In After the Hunt, Giulia Piersanti’s muted costume design also reflects the greyness inherent in the moral ambiguity of the film.

Higher education in crisis

Themes of Dark Academia are also being referenced in scholarship on the psychosocial harm taking place within corporate university settings.

In After the Hunt, the phrase “the crisis of higher education” – typically a news heading – is repurposed as character dialogue.

Universities in the United States have been targeted with underfunding, a dismantling of diversity programs and existential threats to academic freedom. And graduate research studies are not exempt.

Closer to home, humanities and creative arts programs are being restructured, or erased altogether.

Is it too far of a stretch to imagine that the romanticism of studying the classics, the liberal or creative arts may one day only exist on screen?

In these new campus films the university itself is a key character – and its traits are found wanting.

In Sorry, Baby, Agnes feels the cold hand of the institution when her PhD supervisor flees to take a job at a new university. In After the Hunt, the Dean tells Alma “optics” matter most. While Agnes and Alma ultimately succeed in their tenure as professors, it feels a hollow victory.

These films bring dark stories of campus life to the screen in new ways. They explore generational values and distil the sociopolitical anxieties that surround universities today into fictional forms.

In particular, they conjure an ethical (and institutional) greyness perceived to be operating in higher education settings and draw on current affairs in the sector for raw material.

Last week, we saw the Australian government implement a set of “University Governance Principles” to restore public trust in universities. Perhaps an Australian film in this genre is coming next.

Author Bio: Alex Munt is Associate Professor, Media Arts & Production at the University of Technology Sydney