For many years, this postcard was taped to my office door:

For many years, this postcard was taped to my office door:

It’s funny because it’s true. The machines really do talk about us behind our backs.

Machines talking to machines helped me pay for the delicious cardamom buns I bought from the new branch of Under bakery this morning:

OK, technically I was watching while the machine at the shop talked to the machine at the bank about my finances, but what they said to each other was invisible: a bunch of zeros and ones, mediated by my phone. The bun seller and I were comfortable the conversation was accurate and trustworthy, even if we couldn’t see it.

This kind of machine chatter is useful.

More disturbing is what machines say about you to other machines without you knowing.

Recently, a couple of people close to me have been encountered big health challenges. Of course, I hit Dr Google for information on how to help them. During one of these searches, the cookies from a (reputable) medical information website must have told Google what was happening to people in my life. Google shared/sold this information on. How do I know? Despite not sharing any of these health details on any Meta platform, even as a DM or a search, my algorithmic feed in Instagram started to show me ‘relevant content’ and push certain health products and services.

Ugh. I have enough of that in real life.

I wish the Google and Meta Machines would stop gossiping about me behind my back. It’s bad enough that stupid cookies and algorithms collude to follow you from platform to platform. It’s only going to get worse as machines get smarter. 2025 is the year that AI has well and truly joined the online machine group chat. This change has big implications for us as researchers, but first let’s think about what kind of conversations AI is having, both with us and with other non-human entities.

They say sticks and stones break bones, but words will never hurt, but we know that’s not strictly true. When it comes to fucking us up through words, AI has untapped potential. Consider the many stories about chatbots causing mental breakdowns; a topic that researchers are now (thankfully) starting to look into. Not all these machines are created equal in the mind-fuckery business. The engineers at Anthropic (who build Claude) bill themselves as ‘responsible’ (it’s a relative term); they even have a constitution (for what it’s worth).

Anthropic at least says they respect your privacy, which is more than you can say about OpenAI.

OpenAI wants to really know you – so that it can grow around you and your work, like a creeper vine. When ivy grows over a house it looks very picturesque, but soon the house becomes structurally unstable. The ivy loosens the mortar between the bricks and replaces it with plant suckers. If you kill the ivy, the house literally falls apart. Likewise, ChatGPT would like to understand everything about you and your work so you get dependent on it and keep paying. Or, preferably, it gains enough information to steal your work altogether.

And yet – I still use it.

ChatGPT convinces you to willingly co-operate in this project the same way the bank machine did in my first example: by being really, really useful. ChatGPT is qualitatively different to Claude because it remembers me between chats. It’s formed a ‘theory of mind’ that helps it anticipate my needs and respond in useful ways. Here’s how it explained this new feature to me:

“Because I’ve worked with Inger for a while, I have a rough internal model of her work, audience and preferred voice. When she asks for help, I don’t just generate generic academic advice: I adapt explanations, examples and templates to fit her context – thesis writers, supervisors, time-poor academics – and the way she usually speaks and writes. She still decides what to keep, cut or rewrite, but my suggestions start much closer to what she actually needs than if every interaction began from scratch.”

It’s true. I treat ChatGPT like an autistic co-worker whose special interest is my work (before you get upset about that statement, I think the special interests side of Autism can be a fantastic academic asset).

If you think ChatGPT is useless, try restricting the topics of conversation: you will get better results. A broad spread of topics confuses ChatGPT’s sense of who you are and what you want. Anything algorithmic can get confused if you are giving it data from different people. You may have noticed this if you share Spotify , Netflix or Apple music with your family. The algos will try and merge your taste, often making a mess. My pod co-host, Jason, finds Siri plays the urban rap his son prefers whenever he asks for music from the house smart speakers they share (luckily, they both agree on ACDC).

I noticed ChatGPT’s ability to anticipate my needs degraded when my son, Brendan, was sharing my account. I wanted to make sure he was complying to his university AI ethics code. He was willing to put up with mother-surveillance to get extra grunt from my paid account. Shortly after we came to this agreement, ChatGPT started offering solutions and weird digressions that were not helpful.

To stop the algorithmic confusion, I asked Brendan to tell the machine at the start of each chat that he was the user, not me. He didn’t use it that much, but ChatGPT was still able to form a pretty good idea of who he is from a small number of chats:

From previous conversations, I know the following concrete things:

-

-

Relationship to you: Brendan is your son.

-

Discipline / interests: He works on machine learning / pattern recognition and related data-science topics.

-

Activities we’ve done together here:

-

We’ve troubleshot Python machine-learning assignments (e.g. logistic regression, SVMs, kNN, ROC–AUC, confusion matrices, tuning hyperparameters).

-

He’s been involved in building R scripts (using tidyverse, etc.) to clean and transform data for research purposes.

-

-

Role in your world: He shows up as a collaborator and technical helper on your projects, particularly around code and data.

-

When pressed to describe Brendan, ChatGPT guessed he was ‘Male, in his early 20s, studying at uni, probably data science or engineering’.

That’s pretty accurate. Brendan is 24 but his major was psychology (clearly he didn’t need help with those assignments). His minor was data science and his chat history shows him interacting with ChatGPT as a kind of personal tutor to help him debug code he’d written. I still don’t know how the machine worked out his age – maybe it’s worked out mine and extrapolated.

Now I know ChatGPT is so creepy, I never talk to it about personal matters. In case you’re wondering – this post is written with my own human brain and fingers. I am not sharing it with ChatGPT, even for editorial help (you’ll probably see more typos – sorry not sorry). The reason I’m only talking about my health anxieties to millions of humans on the internet is simple: I don’t want the machines at Open AI to know my business. I bet they would be even worse gossips than the machines at Google and Meta.

How do I know? ChatGPT recently popped up as a referrer to this blog – so it’s talking about me behind my back already. But this time, to people seeking help about the PhD. It sees me as an expert voice and using my content to make answers. Sometimes it must be making reference to me as the source of its advice, giving users a link to click on which takes them to http://www.thesiswhisperer.com

I could get pissed off that ChatGPT is stealing and riffing on my work, but actually there are some advantages for me. This is a new form of AI SEO (search engine optimisation) that I think will be of growing importance for us as researchers. Academic profile raising used to be all about social media game, now the game has changed.

Let me demonstrate some of the new rules of the game, with a bit of analysis of my own Whisperer stats.

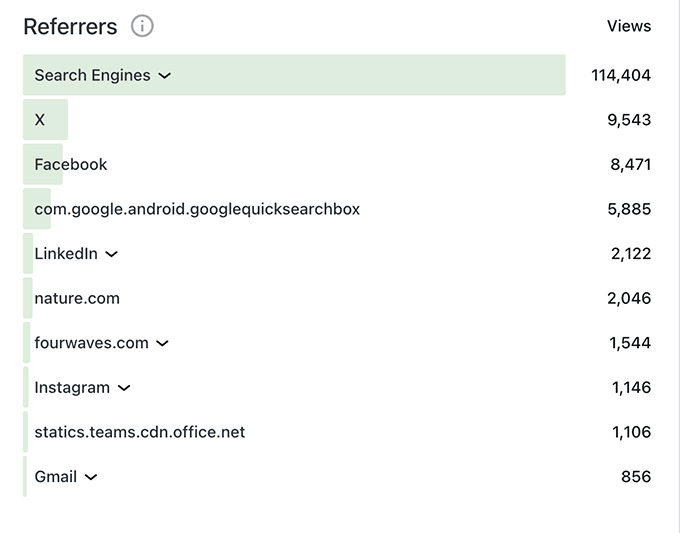

Currently there are a touch over 41,000 email subscribers to this blog – thank you all! (This is a reminder that my blog is just like a Substack newsletter, scroll around, you will find the place to share your email). Other people find me through Google searches and seeing my posts on social media. Lately, as I wrote about here, social media has become enshittified. Platforms do not want to let eyeballs stray away from the ads, so any posts with a link to a blog tend to be down-ranked. Lets look at the referrer list from 2023, pre-ChatGPT era:

Search referrals Calendar year 2023

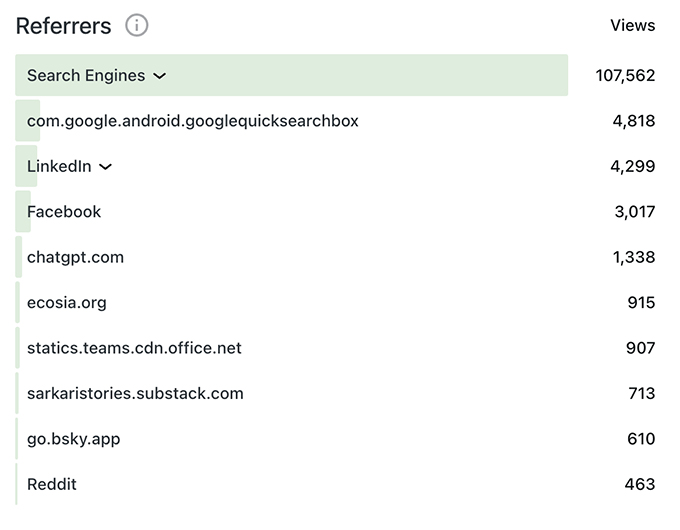

Collectively, search engines were the majority of the referrers, followed by Twitter (now X – that burning trash fire of a site). Let’s compare with the stats from this year. Social media referrals are way down and X has disappeared (I left in late 2023). Look at number five: there’s ChatGPT with 1300 odd referrals this year:

Graph showing search engine results about the same, but no X and the emergence of ChatGPT

And the Chat GPT traffic is growing – roughly doubling month on month. In a world being eroded by AI slop, I think it’s important that researchers know about how AI ranks us in searches and uses our work. You have to meet the people where they are – and they are using AI to find information. Showing up in an AI search is research impact.

I’m sorry, I don’t make the rules.

Even if you HATE AI (and I know many do) I don’t think you can ignore what is happening here.

I teach researchers how to raise their profile and create research impact, inside and outside of ANU. For many years this involved teaching people how to be useful and amusing on Twitter. There’s a lot wrong with the current ‘AI revolution’, for sure, but the advice I have to offer about optimising for AI is… good?

Just do the research and make sure people can find it.

You don’t have to learn a new skill set, you just have to do the work. I like this message. Of course, there’s a twist in the tale. Machines have to be able to read your work.

Most academics produce big ‘blobs’ of text in the form of papers and lodge them behind journal paywalls, which are designed to prevent machine ‘crawling’. Your other challenge is help machines connect your work to you – it’s good to be named, but also important people have ways back to the original source so they can verify the information.

AI SEO is an emerging field, but here’s a couple of suggestions if you want to get started

(ChatGPT generated this for me, from our extended research on the topic)

-

Chunk your content into small, self-contained sections. Use clear headings, short paragraphs, bullets and summaries so assistants can “lift” coherent chunks rather than wade through text blobs. Microsoft’s AI search guidance and SEO folk both emphasise this strategy– e.g. Microsoft: Optimizing Your Content for Inclusion in AI Search Answers

-

If you have a website or public newsletter, write some content in Q&A form, using real questions as headings. AI search favours pages that directly answer natural-language questions in discrete blocks (Q&A, FAQs, “How do I…?” sections)

– e.g. GoVisible: The anatomy of AI-optimised content. I assume, although I don’t know for sure, that doing interviews with journalists would produce similar content for machines to parse. -

Tidy up your metadata and identity signals. When putting up pre-prints, pay attention to page titles, headings and descriptions. Keep your name and affiliations consistent across ORCID, institutional profiles and personal sites so systems can recognise you as one “entity” around a topic – e.g. LLMRefs summary of Microsoft’s AI visibility signals.

-

Make at least one version of your key work open and easily retrievable. RAG-style systems (OpenAI, Azure, Copilot, etc.) can only ground answers in material they can actually fetch, so preprints, repositories and open summaries matter. See – e.g. OpenAI explainer on Retrieval-Augmented Generation

-

Assume a large share of “readers” are now bots as well as humans. Recent traffic studies suggest automated agents are around half of all web requests globally, driven in part by AI and LLM crawlers, so writing for machine legibility is a consideration for anyone wanting to be a publicly accessible writer – e.g. Imperva 2024 Bad Bot Report (summary)

Note that AI agents conduct searches to find content, so your visibility on Google is still important. I have a 15 year head start on this: there are nearly 1 million words of Thesis Whisperer content out there for the machines to eat. More importantly, this content is indexed by many universities, so I am always ranked high in Google searches.

You can get a similar ‘halo’ effect by making sure your work is described somewhere on your university webpages. A good enough reason to get in touch with the University media team. In my opinion, universities need to be pro-active about this new trend and create spaces for their researchers to put content for machines to read. (If you are not sure what to do, I am available for consulting gigs). But it took them 10 years to get the memo on social media, just when it ceased being that important, so I am not holding my breath.

I think its only pragmatic to consider how machines are talking about you behind your back. By all means, maintain the rage if you truly hate AI, but if you are a researcher who wants to be known for your expertise, think about how you become machine readable. But be careful what you tell the machines about your life and your feelings – they can’t be trusted not to gossip.

(I’m pleased to report: those near and dear to me with difficult health situations are receiving the best of care. If I must eat my feelings in the form of cardamon buns, it could be worse.)