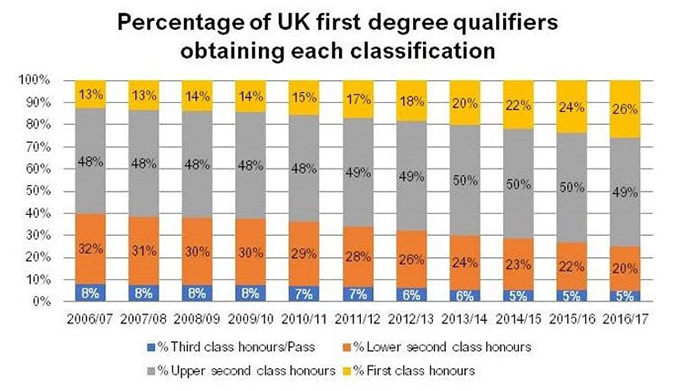

More than a quarter of UK graduates received a first-class degree, and nearly half received an upper second-class award in 2016-2017. This means 75% of graduates gained “good degrees” – up from 60% ten years ago.

Repeated media outcry and government condemnation over this upward drift, continues to fuel debates over the robustness of the current degree classification system and slipping academic standards – bringing with it the charge of grade inflation.

But evidence suggests students are getting higher grades for valid reasons – such as improved outcomes in primary, secondary and further education – meaning students are better prepared for higher education.

Steps taken by universities in recent years have also improved student performance. These include increased emphasise on teaching excellence, assessment and student feedback. As well as investments in campus facilities, such as 24-hour libraries, and improved student support services.

There are other developments that have also contributed to rising grades, such as changes to subject mix, course and student characteristics. For example, more women now go to university, and women are 5% more likely to get good degrees.

Students may also be motivated to work harder, as they are paying consumers and the graduate job market they will enter is highly competitive.

HESA data. Author provided

Academic studies support the argument that grade increases are genuine. Here, rising grades are the result of what education economists call improved “efficiency” — where better outputs are achieved from inputs. But despite this, the government has asked the new Office for Students to look at the significant rise in the number of good degrees awarded in the last few years.

Universities like good grades

While more top grades doesn’t necessarily mean degree classification inflation is happening, the increases in the number of good degrees cannot be entirely explained by the reasons above.

Critics argue that the “degree algorithms” universities use to determine final degree classifications are inflating grades. Degree algorithms are the rules and procedures that convert all the grades a student has achieved during their studies into one final classification.

Over the last ten years significant changes have been made to degree algorithms by many universities, to achieve “competitor alignment”. This is where a university seeks to match the percentage of good degrees awarded by competitor institutions.

The proportion of good degrees a university awards is included in league tables – where a greater number of good degrees means a higher ranking. Universities therefore have a reason to award more of them. Widespread practices of tweaking the rules by changing the algorithm to gain league table advantages, has fuelled sector wide grade inflation.

This produces artificially high average grades, compressing all grades at the top of the classification scale. And there have also been reports that lecturers are under pressure from senior management to award more high grades when marking.

On top of this, student satisfaction and alumni donations are also now of much higher importance to universities. Students are more satisfied with higher grades than lower grades. And graduates with good degrees are happy alumni who are more likely to donate money later in life.

Graduate employers

So many graduates – all with the top grades – creates a challenge for graduate recruiters, who want to distinguish between differing academic abilities and skills. One solution is to supplement classifications with additional detail.

Grade Point Average and the Higher Education Achievement Report – which gives a detailed picture of a student’s extracurricular activities, prizes and voluntary work – providing a holistic view of students’ achievements. Both were recommended by the 2007 Burgess Report, which said that “the UK honours degree classification system was no longer fit for purpose”.

Record number of university students graduated with first-class degrees. Shutterstock

Some of UK’s largest graduate employers like Ernst & Young and Penguin Random House Publishers, no longer use degree classifications as entry criteria for their graduate schemes. Instead, they use their own assessment centres to filter applicants. Google also announced its move to debunk college transcripts as a hiring metric in their recruitment processes. Such reactions from employers means universities need to do more to rebuild confidence in the value of a degree certificate.

Government response

It is easy then to understand why the robustness of the classification system has come under sustained criticism. The UK honours degree is a highly valued qualification and recognised brand, inseparable from higher education which is an important sector of the economy.

The government has warned against “gaming behaviour” and that long-term inflation trends will undermine the credibility of UK degrees. This also makes it difficult to differentiate genuine grade improvements from artificial grade inflation. But it is unlikely that universities, left to their own devices, will address grade inflation.

The former universities minister challenged universities to ensure degree outcomes genuinely reflect improvements in student attainment, calling for a wholesale sector wide reform. A project has since been launched to look into the issue.

The new regulatory framework for higher education empowers the Office for Students to take action against universities failing to comply with sector agreed standards. The government has also added an analysis of degree trends to the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF).

So while the government wants to intervene and mitigate against the risks of grade inflation at universities, it is clear that the myriad of complex reasons behind rising grades will make this a very challenging task.

Author Bio: Andrew Gunn is a Researcher in Higher Education Policy and Priya Kapade is a Postgraduate Researcher in Higher Education both at the University of Leeds