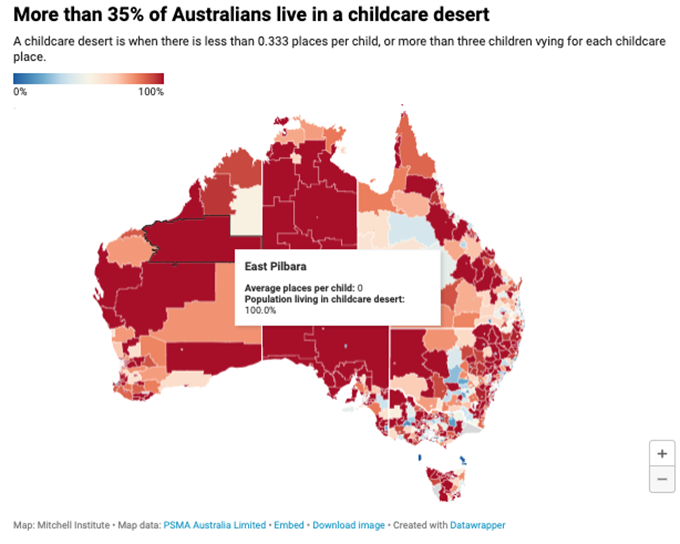

About 9 million Australians, 35% of the population, live in neighbourhoods classified as childcare deserts – populated areas where there are more than three children per childcare place.

In the first research of its kind in Australia, the Mitchell Institute has examined access to childcare in more than 50,000 neighbourhoods across the country.

We found about 1.1 million Australians live in regional and remote areas where there is no childcare available at all.

The map below shows the accessibility of childcare across Australia. Areas in orange and red indicate suburbs more likely to have childcare deserts. Areas of blue indicate where there is greater relative supply.

There are childcare deserts in all states and territories, and in all capital cities.

For instance, Avoca, in Victoria’s Central Highlands, has no childcare places at all. This means 100% of the population live in a childcare desert. In Leinster, around 300km north of Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, there are 5.62 children for every childcare place, and 79% of the population live in a childcare desert.

Blue areas on our map, which represent places with the best access to childcare, are mostly concentrated in metropolitan areas and the eastern states. Queensland has some of the highest childcare availability in the country, but even here there are large differences between particular areas.

For instance, Rockhampton has relatively high levels of childcare accessibility, with roughly one childcare place for every two children. But in the nearby town of Yeppoon, about 63% of people live in a childcare desert.

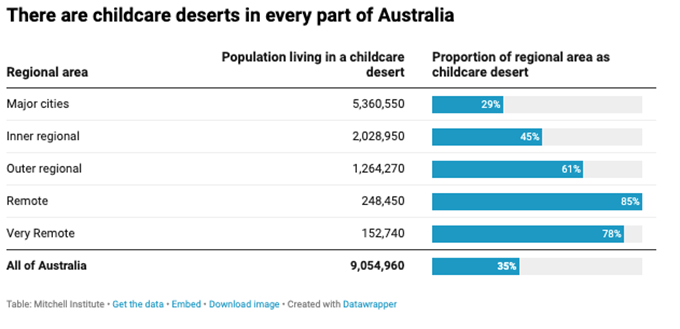

Childcare deserts are more likely to be in regional areas

Australians living outside major cities are more likely to be living in an area we classify as a childcare desert.

In rural and regional areas, childcare deserts may mean a total absence of services, or too few places available to meet the potential demand. The impact of this means families may need to travel a lot further to access childcare.

Childcare deserts are an issue in metropolitan areas too. More than 5.3 million Australians who live in major cities, or about 29%, are in areas we classify as childcare deserts.

Families living in deserts in major cities may still be able to access childcare, but they may have to travel further or face more competition for available places.

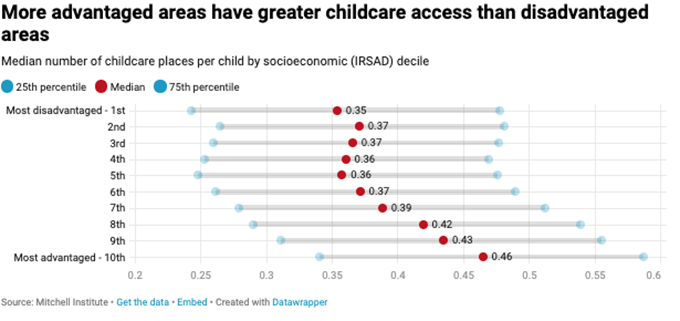

Disadvantaged areas have less access to childcare

We also looked at the socioeconomic status of neighbourhoods to examine how relative disadvantage and advantage affects access to childcare.

We found for neighbourhoods in the lower 60% of socioeconomic status, the median childcare accessibility is around 0.35-0.37 places per child. This is below the national median of 0.38 places per child.

Within the top 40% of neighbourhoods by socioeconomic status, as advantage increases so does the median number of childcare places available per child.

Neighbourhoods in the 10% most advantaged areas have the best access to childcare, with one place for every 2.17 children on average.

High-quality early childhood education and care enables children, particularly from disadvantaged backgrounds, to succeed later in life.

Our findings suggests that, overall, it is the children and families who would benefit most from high quality childcare who have the least access.

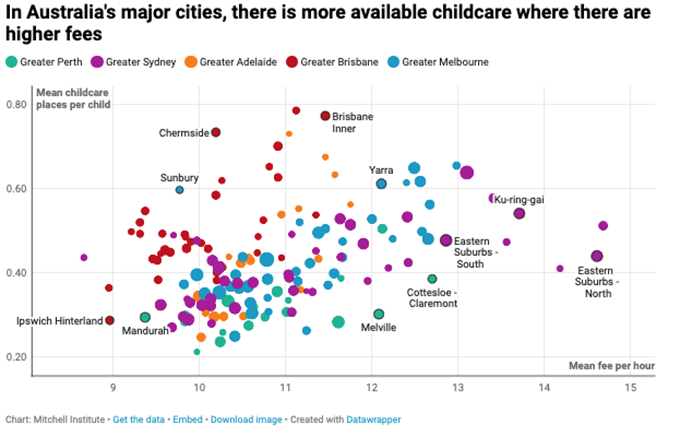

There is greater access where there are higher fees

Part of the reason for greater access in more advantaged areas is because Australia’s childcare system encourages providers to go where there is the lowest risk and the greatest reward.

One way of illustrating this is to explore the correlation between price and accessibility.

We examined the relationship between the median cost per hour of childcare and the average childcare places per child in the five major capital cities with a population over 1 million people.

We found areas with the greatest supply of childcare are also areas where providers charge higher fees.

For instance, the area of North Sydney and Mosman has the most expensive childcare in Australia, and also some of the highest levels of childcare accessibility in Greater Sydney. This compares with Mount Druitt in Western Sydney which has some of the cheapest childcare in Greater Sydney, but where 89% of the population live in a childcare desert.

This suggests there is an incentive for providers to operate in advantaged areas where they can charge higher fees, even if there is greater competition. This leaves more disadvantaged areas with lower levels of childcare accessibility.

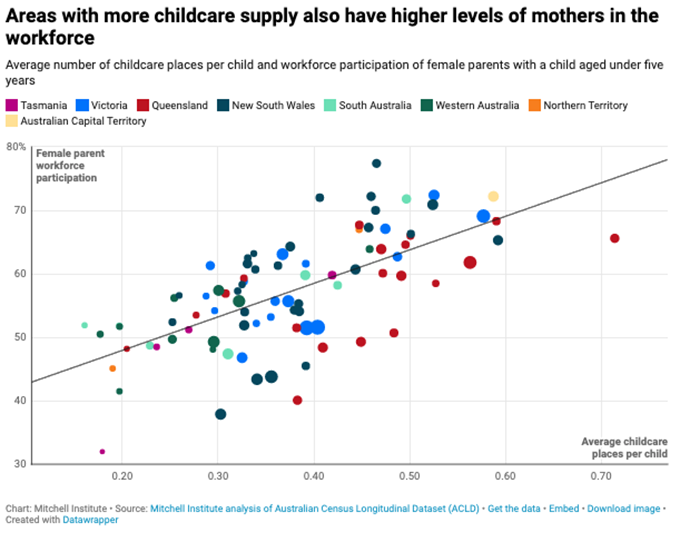

Childcare access linked to female workforce participation

One of the many functions of childcare is to enable greater workforce participation, particularly for women.

We found regions with lower access to childcare also have lower workforce participation rates for women with young children. The inverse can also be seen – regions where more childcare places are available have higher rates of women in the workforce.

For instance, the ACT has some of the highest childcare accessibility and highest levels of workforce participation of mothers with young children. Rural areas such as South East Tasmania, and outback Northern Territory are in childcare deserts and have some of the lowest levels in the country of mothers with young children in the workforce.

The reasons for this association are complex. Lower levels of female workforce participation in an area will affect demand for childcare. It may also be that difficulty in accessing childcare leads parents and carers to choose not to work while their children are young.

Investing in Australia’s early childhood education and care sector

Research from Victoria University shows investment in childcare almost pays for itself, largely due to higher workforce participation.

Other research highlights Australia can get the most out of childcare by making it more affordable, reforming parental leave and better linking the early learning sector to the health system.

Australians deserve much better access to childcare and a system that supports families to make the decisions they believe is best for them.

Most importantly, children need a system that meets their needs so that they can have the best start in life, regardless of where they live or the income of their parents.

Author Bio: Peter Hurley is a Policy Fellow, Mitchell Institute at Victoria University