I am an academic with dyslexia and I would like to share my story with you.

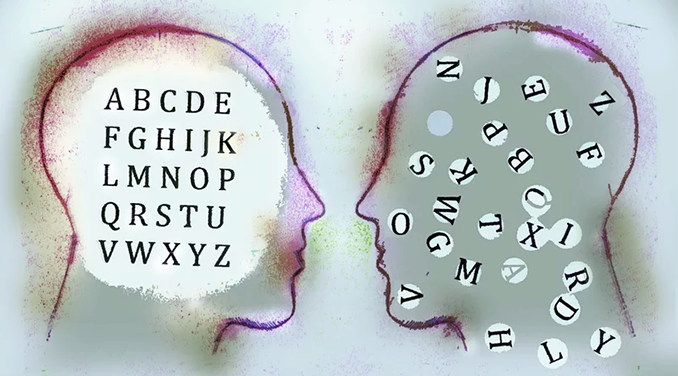

Dyslexia in academia is a conundrum – it is basically a learning difficulty, and coping with dyslexia is a very personal journey. It is different for everyone.

For me, dyslexia affects – among other skills – my maths, sciences and languages, including English. The very skills you need to succeed in the competitive world of academia. What is often so easy for others is difficult for me.

Academia is a place where you are expected to spit out research papers, the more cited and higher impact the better. While I do publish papers, I am not confident in my scientific writing. And I am so slow … my coauthors can get frustrated with my basic grammar errors, and don’t even get me started on statistics!

Still I persist. I go into university every day and work on those papers, determined to get them out. But more recently my career has taken a turn towards science communication – and it turns out that people think I’m quite good at it.

Education is hard

Sticking with the university environment may make me unusual among the dyslexic lot, as many don’t enjoy education.

I’ve always loved school for the learning, the knowledge. But I could not easily share my knowledge through written essays or sitting exams. I failed most subjects miserably at high school and was asked to leave. But this didn’t deter me – I stayed at school and worked my arse off. And still failed!

Growing up in Ireland, unfortunately I had to drop Irish – which is a required language for Irish universities even today. If I wanted to study I had to move to England.

So that is what I did. I followed my dream to an agriculture college, where I studied for a higher national diploma in wildlife management.

High hopes

I, like so many, aspired to a career in academia. It is sold as the ultimate goal – the premier way to gain and share knowledge. I was addicted to learning, and inspired by the engaging and passionate academics who taught me.

However, it has taken nearly 20 years for me to realise that passion alone won’t magically deliver the skills that are so vital to academia. Dyslexic academics need support for their invisible disability, the disability that I still feel so ashamed of.

What kept me going through the hard times? Well an inspirational song helps! Mine is Frank Sinatra’s High Hopes. Take the following verse:

Once there was a silly old ram

Thought he’d punch a hole in a dam

No one could make that ram scram

He kept buttin’ that dam!

Cause he had high hopes

He had high hopes

He’s got high apple pie in the sky hopes.

And us dyslexic lot don’t give up easily – we can be very determined and think outside the box. We can be written off as amounting to nothing – but it is hard to make us “scram” as we keep “buttin’ that dam”. We have tenacity and grit, and are inspired by others who went before us.

Adapt to survive

Despite not getting a first class undergraduate degree, after a year of persistence I gained entry to a PhD program. I researched the diet of badgers and possible connections to cattle tuberculosis (a bacterial disease that can spread through cow herds).

My dyslexia shone as I wrote up my papers and thesis – for example, one of my early reports was on how badgers need a vacation (instead of vaccine) for tuberculosis!

So I had to adapt to survive. I turned to my peers to proofread my work for me. It is hard always needing help, and can really shake your confidence. It would be so much easier just to give up.

So why did I keep going? To make a difference in the world. To teach and inspire – I could do this by presenting my research to the public. I was told by my peers and supervisors that my presentation style was more like a cabaret show – but I always got my message across.

Where I am today

Today I lead the Australian Bird Feeding and Watering Study. This work was initiated on behalf of the public who want to know how best to care for birds in back gardens.

People wanted to know how to provide food to birds safely and correctly, and we are using a citizen science approach to help them find the answers.

Part of the study includes sending frequent update emails on the research. This was a drama for me, as I was so nervous in case bad grammar and spelling slipped through. But I felt I had to be honest with the email recipients.

I explained “I am dyslexic” so they wouldn’t think I was being careless or lazy if mistakes did get through. The support they gave me was overwhelming. They didn’t care that I was dyslexic, and loved the way I wrote.

“My daughter is also dyslexic, and you are an inspiration to her,” one email read, while another told me: “Keep the faith – you are doing great.”

It is only now, after 20 years, that I am starting to find confidence. Finally I have found an aspect of academia that comes naturally to me: writing in a style that is easy to read and understand. For me, this is second-nature – it’s just how my brain works. Big words scare the holy hell out of me, partly because I often can’t pronounce them – let alone spell them.

Here’s me talking about birds in front of the camera. Grainne Cleary, Author provided

So I write more simply than most – is this a bad thing? We are often told to write without passion, and I am still told by some colleagues and collaborators that my writing style will hold me back. I’m told it makes my research too colloquial. Ironic isn’t it – it’s actually what we call science communication.

For now I am going to keep on pushing, helping to break down the walls of academic writing. Maybe they need people like me? And always remember … never underestimate a person with dyslexia – we have grit!

Author Bio: Researcher, School of Life and Environmental Sciences at Deakin University