Perfectionists are sometimes thought of as superheroes: people who are high achievers and seem to always have it all together.

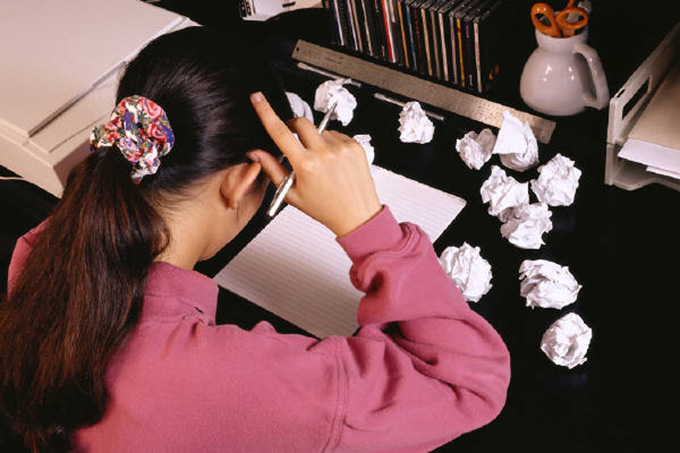

Perfectionism is different from simply trying to do a good job or even seeking excellence. Rather, perfectionism refers to rigidly requiring nothing short of absolute perfection and being highly self-critical.

Our recent study, published in the journal Child Development, examined how perfectionism is affecting teens’ mental health and stress levels during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Exacting standards

While research shows some forms of perfectionism are related to small achievement gains, it also reveals perfectionism is commonly associated with experiencing more health problems along with relationship difficulties.

People higher in perfectionism even show dysregulated immune system functioning.

Perfectionists do not fare any better with respect to their mental health: research indicates perfectionistic individuals report higher levels of depressive symptoms, stress, disordered eating and anxiety compared to their less perfectionistic peers.

Perfectionistic people are particularly susceptible to experiencing these adverse consequences when they are stressed or faced with difficult and uncertain situations, because they tend to be unable to or at least reluctant to adapt to changing situations.

Thus, there is good reason to be highly concerned about perfectionists during the continually evolving pandemic that has been exceptionally stressful for most people.

Perfectionism as personality trait

When measuring perfectionism as a personality trait, psychology researchers identify different “flavours” of perfectionism.

Self-oriented perfectionism refers to requiring perfection from oneself. People high in self-oriented perfectionism demand perfection from themselves and are incredibly hard on themselves when they do not meet those demands.

Socially prescribed perfectionism refers to the belief or perception that others require perfection. Individuals who are high in socially prescribed perfectionism think others demand perfection from them, are critical of them and believe that they will never measure up to others’ expectations.

These forms of perfectionism are commonly observed in teens, a group that experiences relatively high levels of perfectionism. Research shows that approximately one in four youth are highly perfectionistic.

Lack of closure, opportunities

It is important to focus on how young people are doing during these difficult times. Unlike adults who have already gained their sense of independence, the pandemic and its accompanying restrictions have held teens back in a state of suspended reality.

For example, many teens have completely missed out on significant developmental milestones such as graduations and proms, leaving them feeling lost due to a lack of closure on important chapters of their lives.

Government-mandated lockdowns that were put in place to slow the spread of COVID-19 forced young people into isolation where they were often separated from friends and family for extended periods of time. School closures also led to substantial interruptions to young people’s schooling, which is associated with gaps in in educational achievement.

It is not hard to imagine how difficult gaps would be for young perfectionists who often define themselves by their ability to achieve.

Effects of lockdowns

Our study shows the significant effects lockdowns have had on the self-reported mental health of teens.

We assessed 187 adolescents’ levels of perfectionism, anxiety symptoms, stress and depressive symptoms before the pandemic began and then again during the first and second government-mandated lockdowns that took place in Ontario, Canada.

Results showed an interesting pattern of change with respect to depressive symptoms and stress levels. Depressive symptoms and stress decreased slightly from before the pandemic began to the first lockdown and then increased dramatically from the first to second lockdown.

Although we cannot be sure, one possible explanation for these findings is that teens were able to take a much-needed break from their busy and possibly overscheduled lives during the first lockdown, which resulted in some relief of depressive symptoms and stress.

However, by the time the second lockdown occurred, teens may have been feeling demoralized and hopeless as the pandemic continued to take its toll on everyone, resulting in higher levels of stress and depressive symptoms.

How perfectionists fared

A key finding is that teen perfectionists are not faring as well during the pandemic compared to their non-perfectionistic peers. Teens who demanded perfection from themselves (self-oriented perfectionists) were more depressed, anxious and stressed than those who did not tend to demand perfection from themselves over the course of the pandemic.

Results also showed that when teens experienced higher than their typical levels of self-oriented perfectionism, they were also more anxious, but not more depressed or stressed.

Teenagers who believed that others demanded perfection from them were more depressed and stressed than those who did not have such beliefs during the pandemic.

We also found that when teens experienced more of these beliefs than usual, they were more depressed, but not more anxious or stressed.

Struggles behind the mask

Taken together, these findings support the idea that perfectionistic teens are more vulnerable to mental health problems and greater stress compared to their non-perfectionistic peers during the pandemic.

It is important to recognize that although teen perfectionists often appear to be doing well on the surface, they are not superheroes who are impervious to hardships.

Instead, they are young people who are often in distress and struggling behind their mask of perfection and in need of support during these difficult times.

Author Bio: Danielle S. Molnar is Associate Professor of Child and Youth Studies; Canada Research Chair (Tier II) Adjustment and Well-Being in Children and Youth, Dawn Zinga is Professor of Child and Youth Studies; Associate Dean, Graduate Studies and Research, Faculty of Social Sciences and Melissa Blackburn is a PhD Candidate, Child and Youth Studies, Brock University