The oral is more and more valued, whether with the vogue of eloquence competitions, the proliferation of popularization accounts on YouTube or the creation of a large oral at the baccalaureate. The speaker is expected to speak correctly, with an appropriate syntax, audibly, articulating and that his words interest the listeners. But before being able to express themselves and defend ideas in such frameworks, students still need a certain amount of knowledge. And to accompany, in each discipline, the pupils in this reflective activity of thought, it is a question of setting up in the class a working oral.

What are the characteristics of this oral allowing everyone to learn? And, how to make teachers aware of its importance?

Although oral language is mentioned in school curricula, it is very little present as an object of teaching in the timetables, from primary school to high school.

Nevertheless, oral communication is the preferred means of communication between teachers and students. It is also mainly for this reason that it is not taught. As it is considered more “natural” and more “spontaneous” than writing, teachers are used to using the spoken word to help the most vulnerable pupils in reading and writing, which contributes to considering it as a means of teaching rather than a real object of teaching.

Élisabeth Bautier , sociologist, warns, however, that the classes have never been so talkative, but that, for all that, the specificities of this oral learning are not taught.

Building knowledge

Indeed, if the oral language used in the classroom is closer to everyday language than to the oral language used in school learning (which is more like writing) and it is not not perceived as a teaching object in its own right, this can create misunderstandings among pupils as to the meaning and purpose of oral interventions at school, which can further deepen inequalities.

In fact, language is neither natural nor transparent; its uses are always dependent on a context or a human activity which leads Jaubert, Rebière and Bernié to say that the uses of language at school are specific to each discipline. Pupils must learn the ways of acting, speaking and thinking specific to each of these subjects, a necessary condition for building together grammatical knowledge, in the case of the work that we present.

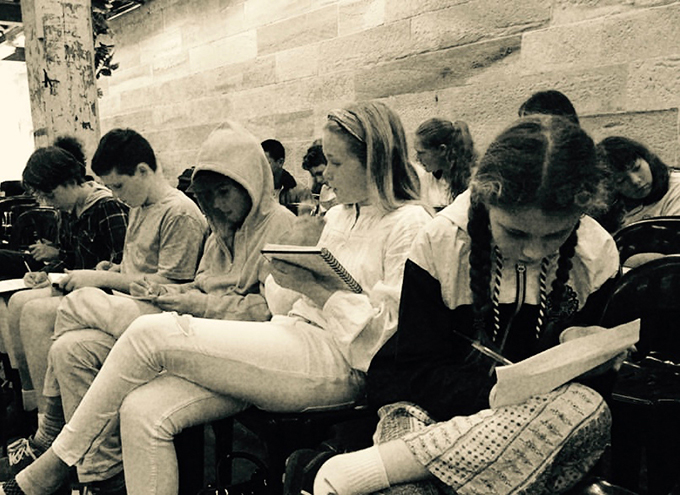

Within the framework of a collaborative research of two consecutive years, on the use of oral in the teaching of grammar in cycle 3 (students in CM1/CM2), we filmed four teachers on the grammatical notion “Phrase simple vs. complex sentence” (French Grammar, p 22 – paragraph 2.1). During the interviews that followed between researchers and participants and between participants themselves, they were able to view their practices and analyze them individually and then collectively to become aware of the role of language in the construction of knowledge.

From the written transcriptions of the videos of the sessions, we did a quantitative analysis to establish the percentages of speaking time for each and to obtain the average length of the statements of the students and each teacher by counting the number of words of their statements.

Beyond the comparison of the speaking times and the length of the statements between the two years, we carried out a qualitative analysis of the discourse of the teachers and the students to identify what had changed (the nature of the statements, closed/open questions on the part of the teachers, yes/no answers, presence of arguments among the pupils, etc.).

Reflect on their practices

During the interviews for the first year’s sessions, the teachers realize that they talk too much (more than 80% of speaking time) and that their total questions (is that?) or closed questions (which often do not wait only one or two words), have an impact on the length of the students’ statements (¾ words) and on the content (very few elements of knowledge). In the sessions of the second year, we observe less unbalanced speaking times (around 70%) and a longer average length of the students’ statements (more than 6 words on average).

Indeed, the teachers mobilize fewer closed questions, encourage the pupils to complete, to justify their remarks and to use precise grammatical terms. As a result, students formulate longer answers, seek to explain and also mobilize more varied uses of language, specific to the grammar and knowledge at stake, for example:

- describe a complex sentence: “it contains two verbs, does and loses”

- establish a definition of this notion: “a complex sentence is a sentence that has at least two verbs and even more”

- bring a counter-argument to what a comrade explained: “but it’s not the length that makes it a complex sentence”.

Teaching the spoken word and its uses within the framework of the disciplines, having pupils build knowledge by working on the language that makes it explicit, can give pupils meaning in the spoken word at school, because, as Élisabeth Bautier writes, ” to speak to learn is to learn to speak”.

The spoken language at school is therefore multiple, which makes it difficult to perceive and teach it. For students to be able to use the spoken word to learn, it is essential that teachers know it, recognize it and use it in their classes. It is therefore necessary that the linguistic construction of knowledge be addressed in teacher training to make this oral less invisible. Watching filmed teaching sessions and discussing them between teachers and researchers in the context of collaborative research seems to be a promising avenue in the initial or continuing training of teachers.

Author Bio: Magali Durrieu-Gardelle is a PhD student in education sciences at the University of Bordeaux