Many apps and algorithms that feature prominently in our lives are, essentially, black boxes: We have no idea how they accomplish what they do; we just know they work. Or at least we think we do. Most recently this became apparent when The New York Times revealed that Uber used a system it called “greyballing” to show certain users phantom cars and prevent them from getting rides through the Uber app.

In essence, these users – often government officials or others Uber feared might interfere with the company’s services – were shown a completely different (and deliberately false) view of Uber’s data, without their knowledge or consent. Given the ubiquity of the Uber service – and the controversy that surrounds Uber in general – this article immediately raised questions about the fairness and legality of Uber’s practices. For example, why should people trust Uber’s surge prices if the app and data can be manipulated arbitrarily, at will by Uber?

Unfortunately, platforms like Uber are almost always closed: Users, regulators and policymakers typically have no way to know whether, or to what extent, apps and algorithms are behaving in questionable ways. The greyballing was only discovered because its existence was leaked to the media by current and former Uber employees.

But algorithms are widely used in many contexts, including selecting job applicants when hiring, estimating borrowers’ creditworthiness, determining where police departments should deploy patrol officers and even setting bail for criminal suspects.

In all of these cases, the output of the algorithm can have enormous consequences on people’s lives, and yet we often lack a basic understanding of whether they may be biased, unfair or discriminatory. It’s a concern shared by government agencies and scholars alike.

Running up against the law

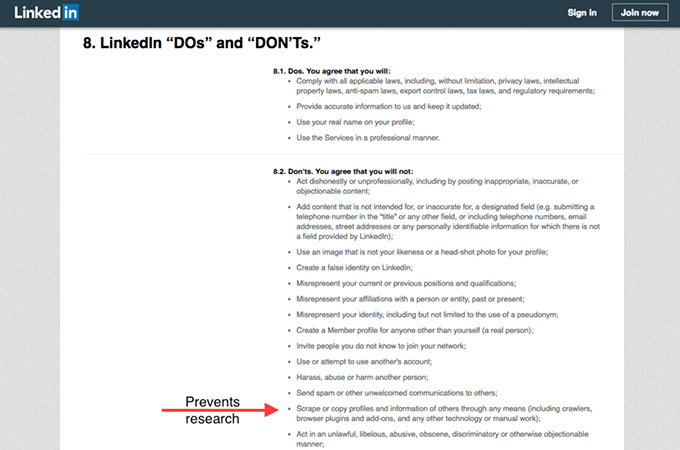

Our own research seeks to identify these problems through study and scholarship, without needing to wait for whistle-blowers to spill the beans. We leverage real users and fake accounts created by us to compile data from online services. Using these data, we try to tease out how black-box algorithms work: What data do they use? How do user characteristics affect the output of the algorithm? Does the system do things that a normal person might find questionable? Of course, companies view their algorithms and data sets as proprietary, and are loath to open them up to outside scrutiny, especially when it may reveal embarrassing things (like attempts to manipulate law enforcement).

In effect, our goal is to increase the transparency of black-box algorithms (like those used by Uber) that affect our daily lives, and to make algorithms and their human designers accountable to social and legal norms. We’re developing ways for researchers, regulators and policymakers to measure these systems and identify instances of unfairness and discrimination.

But there is a significant legal barrier, one that we think effectively ensures the American public is, and will stay, in the dark about how these computerized systems work, and whether they’re fair and equitable to everyone. It’s called the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA). It’s the country’s main “anti-hacking” law, originally passed in 1986 and broadened in 1996. And we’re among a group of scholars and news organizations who have sued to overturn key provisions that block researchers like us from investigating these crucial elements of modern American life.

Letting companies make the rules

Among other things, the CFAA imposes civil and criminal penalties on anyone who “exceeds authorized access” to any computer. This might seem relatively benign and vague, but the vagueness is part of the problem. Some courts and prosecutors have taken the position that it “exceeds authorized access” to do anything contrary to a website’s or company’s Terms of Service. These are the long screens of legalese users must agree to – usually without having read a word of them – before using a website or a piece of software.

Unfortunately, many Terms of Service contain what we consider egregious claims and limitations on users.

- Verizon and AT&T included a prohibition from criticizing the company when using their internet service, threatening to cut off critics’ internet access, even if the criticism was fair, accurate and true.

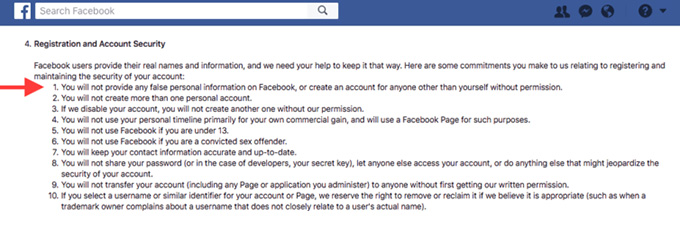

- Facebook disallows providing any false personal information in one’s Facebook profile. That’s a problem for anyone who wants to protect their privacy by using a pseudonym or giving a false age, especially since Facebook’s business model is entirely based on mining users’ personal data to serve targeted ads.

- Internships.com, a website for finding internship opportunities, had a provision allowing them to charge US$50,000 to anyone who used a web scraper to collect data from their website. This threat prevents researchers like us from examining the site, to look for issues like hiring discrimination and bias.

If, as prosecutors and courts have successfully argued, violating Terms of Service agreements can violate the CFAA, anyone who did any of these things – and anything else contained in any similar document – would be violating federal law and exposed to both criminal penalties and civil liability. In essence, we think the current interpretation of the CFAA lets companies write federal law.

Faust 2.0: Mephistopheles encounters the End User License Agreement, also often called ‘Terms of Service.’ Randall Munroe/XKCD, CC BY-NC

Ensuring the law is clear

Along with other researchers and media organizations, we are plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed last year by the ACLU challenging the provision of the CFAA that has been used to equate Terms of Service violations with breaking federal law. This connection is a serious impediment to the goals of algorithmic transparency and accountability: The CFAA was not intended to be a shield that blocks companies from public scrutiny. Yet that is what the prevailing legal interpretations of the law allow.

In the past, independent scrutiny has been crucial in identifying pernicious business practices like discriminatory hiring practices and redlining (illegally denying loans to customers based on race). For the good of modern society, researchers need the ability to audit algorithms without fear of legal reprisal.

On a personal level, the legal threat posed by the CFAA takes a toll on our research. CFAA violations are punishable with jail time and large fines. (To see an example of how large the stakes can be, consider how programmer and activist Aaron Swartz was charged under the CFAA.) In the past, we have abandoned projects because the risks seemed too great, or changed our methods to avoid particular Terms of Service minefields. But, even with this abundance of caution, we, our collaborators, and our students choose to put ourselves at risk every time we begin a new research project.

Currently, our lawsuit is pending before a federal judge in the D.C. District Court, while we await the court’s response to the government’s request that the suit be dismissed. However, our suit is already providing positive results: As part of its filings, the Department of Justice publicly released a previously unknown 2014 memorandum containing guidelines for federal prosecutors bringing charges under the CFAA. On one hand, the guidelines suggest that federal prosecution may not be warranted in instances where someone has only breached a website’s Terms of Service, which sounds good. On the other hand, these are only guidelines; they do not change the law itself or its surrounding precedents, and these guidelines could be changed at any time. Changes in the executive branch and in the leadership of the DoJ highlight how fungible these guidelines are.

Ultimately, this lawsuit will bring clarity to what we and our co-plaintiffs see as a dangerously ambiguous and over-broad law. Researchers, journalists and activists should know where the lines are when planning their online investigations.

Author Bios: Christo Wilson is Assistant Professor of Computer and Information Science and Alan Mislove is an Associate Professor of Computer Science at Northeastern University