Never have American universities been so taken to task in French public debates. Rare were the speeches, during the controversy generated by the recent remarks of the Minister of Higher Education on the radical research currents in the French university, which did not refer to the United States by them. ” Demonizing “. Indeed, according to a good number of analyzes, it is from across the Atlantic that one of the most serious contemporary attacks on academic freedom comes.

Cancel culture, Wokeness, Triggers warnings, Safe spaces… so many concepts that the media have seized upon to describe American campuses which, for a few years now, have been the theaters of an unprecedented restriction on freedom of expression, in the name of defense minorities and a new “right not to be offended”. Our French universities are said to be, almost by contagion, from now on also threatened since, according to the minister , “academics say themselves prevented by others from carrying out their research, their studies”.

Academic freedom, a historical principle of American universities

Yet if there is a cornerstone of the American academic and research space, it is academic freedom. Its legal basis is the first amendment to the American Constitution of 1791, the one which guarantees freedom of expression , the founding principle of national identity, against any restriction, particularly from political power. It should be remembered that in France, academic freedom, in the sense of the independence and free expression of teachers and researchers, has been guaranteed at the constitutional level since 1984 .

Even if the constant jurisprudence of the Supreme Court attaches academic freedom to this First Amendment, the American Constitution does not, however, explicitly mention freedom of teaching and research, nor the specific context of universities. It is therefore the academics themselves who have given themselves the means to define and guarantee the exercise of this freedom.

In wake of President Trump’s remarks threatening the institutional autonomy of colleges and universities and undermining the role of faculty, here is a video to explain what #AcademicFreedom is and why it’s so important to protect. https://t.co/qkNG865mGC pic.twitter.com/0ChJJPNCvv

— American Association of University Professors (@AAUP) March 22, 2019

The opportunity is given to them at the beginning of the XX E century by the massive mobilization against the dismissal considered abusive because based on an ideological motive of Edward Ross , professor of economics at Stanford University. In 1915, a large number of academics then formed the American Association of University Professors (AAUP ) and, under the leadership of the philosopher John Dewey, drafted the first declaration on academic freedom.

The stake, for these academics, is a double emancipation. It is about reaffirming academic freedom as a fundamental component of intellectual freedom, alongside freedom of expression, freedom of the press and freedom of religion. But it is also a question of defining the nature of academic freedom as “the freedom to pursue the profession of scholar according to the standards of this profession” ( Finkin and Post, 2009 ), that is to say a freedom whose contours, evolutions and meaning belong to the academics themselves.

In more than a century, the principles of the AAUP charter, reaffirmed in 1940 (freedom of research and publication, freedom of teaching, freedom of expression within and outside the walls of the University) have made the subject of successive revisions and interpretations, establishing itself today as the reference text which allows universities to fulfill their fundamental social mission, that is to say the pursuit of knowledge, as a “common good “. Indeed, it is by guaranteeing academic freedom that teachers and researchers can contribute to the advancement of science and therefore to the progress of society ( Beaud, 2010 ).

It is therefore the universities, in a logic of self-regulation and peer control, that govern and defend the exercise of academic freedom in the United States. Unlike the French, Americans do not expect the legislator to frame this freedom with prohibitions and penal sanctions, because it is the very governance of universities that is organized based on the preservation of the fundamental freedom to seek, say, teach, debate beyond political orientations, ideas, religious confession, ethnicity, gender, and to be able to be judged only by his peers on a purely scientific level ( Compagnon, 2009 ).

Universities as a place of democratic debate

American campuses, despite the great heterogeneity of the system, are in fact places of democratic debate and plurality of opinions.

For the roughly 16 million undergraduate students, training, especially at major research universities, offers a range of course and discipline choices that are beyond that of French universities. The freedom to choose, to test and grope, to change your mind, to explore different fields of knowledge and ways of seeing during the four years of the bachelor – the American license – is part of intellectual training.

The eclecticism of the points of view is also reflected in the associative life which must allow each group, each minority, each community to promote its values and its interests alongside those of the others. Because the universities consider that pluralism, the contradictory debate, the confrontation between schools of thought is what characterizes them and distinguishes them from other organizations. Even potentially disturbing ideas should be presented and discussed in class and across campus as long as the same opportunity for expression is guaranteed.

However, for the past ten years, the maintenance of academic freedom, particularly in its dimension of freedom of expression, has become a permanent struggle in almost all American universities.

The “woke” movement and restrictions on freedom of expression

The threat does not come from government interference or, as in the past, from any religious authority ( McCarthy, 2018 ). Rather, it seems to come from within the campuses themselves, namely from the student community.

Since the 1970s, in order to better reflect the makeup of American society, universities have gradually introduced “diversity policies” . On each campus, historically under-represented groups, such as certain ethnic or gender minorities, or even ex-combatants, have pushed for more pluralism by demanding greater consideration of their history and their uniqueness in the programs of teaching and course content. This is how many universities have introduced so-called “global” studies, thereby indicating approaches that are finally not centered on Europe, taking into account authors and works from other cultural traditions than those of the Western world considered. as historically dominant.

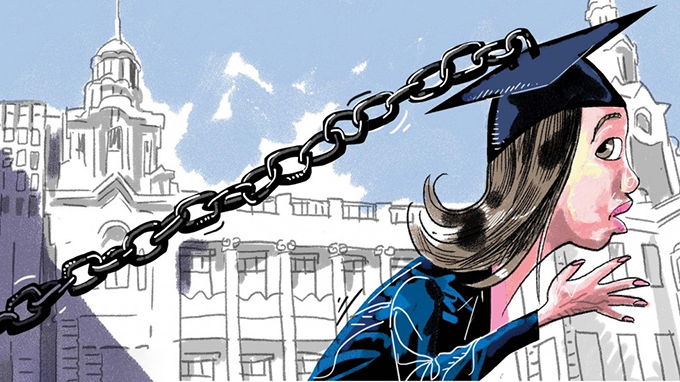

Paradoxically, the attention paid to the representation of all voices and cultures ended up turning against the very principle that had supported it. Respect for pluralism, which requires that all points of view be expressed, studied and debated, has come into conflict with respect for individual sensibilities. Thus, academic freedom, yet guaranteed by the institutions and very much alive on campuses, in practice comes up against the capacity of the students of the new generation of “awakened” (in reference to the “ Woke ” , state of mind of awakening in the face of injustice) to hear opinions or stories contrary to their system of values or deemed to be depreciating towards the identity that defines them.

Over the past decade, many campuses, such as Chicago, Harvard, Pittsburgh, Brown, Georgia Tech, Michigan, Penn, have been rocked by affairs related to the backlash of student groups, sometimes encouraged by professors, in the face of comments deemed offensive, colonialist or offensive to such and such a minority. These reactions can lead to the rejection of the debate in all these forms – hence the name of “cancel culture” or the culture of cancellation – or to the introduction of preventive messages (“trigger warnings”, which aim to prevent the public that they must prepare themselves psychologically for potentially disturbing topics to be discussed).

It can sometimes go as far as requests for dismissal, or even real media lynchings of teachers, amplified by social networks. In July 2020, the suicide of a law professor at the University of Wilmington, North Carolina , was interpreted as the direct consequence of the harassment to which he was the target because of his conservative and provocative remarks on sensitive subjects. like abortion, the death penalty and gender equality. The American NGO Fire ( Foundation for Individual Rights in Education ), whose mission is to protect freedom of expression on university campuses, has seen an unprecedented increase in the number of reports of violations since the summer of 2020.

Faced with such a drift from the principle of “political correctness”, some universities have sought a solution by creating specific spaces for speech, within which we agree to limit freedom of expression so that sensitive people can feel “safe”. “. The usefulness and relevance of these safe spaces have been the subject of many debates in university forums and the media. For some , these places must allow the expression of historically dominated groups, since they would be free from discrimination, racism, sexism or any other hateful behavior; for others , they further marginalize minority opinions because they isolate them and remove them from the arenas of debate.

Money, the sinews of war

Beyond these situations which may seem extreme, the sanitization of public discourse on campuses is a fundamental trend which is also linked to the more general evolution of American higher education and its economic model. Universities, whether private or public, today depend much more on tuition fees, or even on the generosity of individual benefactors (former graduates or parents of students), than on public funding. Students, clients today, are tomorrow’s prescribers and patrons. Not offending their sensitivity is therefore a major issue for university administration. The image of the oldest and most prestigious among them can be permanently tarnished by cases related to the freedom of expression of teachers, with significant consequences on their financing capacities. The higher the reputation of the institution, the higher the risk.

In a famous speech given at the University of Toronto in 2011, Noam Chomsky, professor of linguistics at MIT and a committed intellectual, warned of the effects that the “business model” of universities could have on their ability to maintain themselves. as places of creative and independent reflection and inquiry. He said at the time that the best way to resist the pressures of the funders would be to “simply recognize them as a fact of life” to “fight them categorically, at any cost”. A remedy that could also apply to the current abuses in terms of freedom of expression …

Author Bio: Alessia Lefebure is Director of Studies, Sociologist of Organizations at the School of Advanced Studies in Public Health (EHESP)