From time to time the Universia portal shows how the careers of the future are completely crossed by digital technology: data analyst, cybersecurity specialists, robotics, big data, artificial intelligence… they are part of a neutral tone list and infographic, although crossed by The concept of technoscience. Science and research at the service of technology and the future as much progress.

However, on the one hand, no technology is neutral: gender, race and language bias inhabit it. We already know about soap vending machines that do not recognize black skin and the invisibility of languages other than English on the Web . Likewise, although the future always arrives, it does not do so in the same way for everyone.

For example, while in Latin America we find indigenous communities that, by necessity, have had to learn to manage their own digital communication networks, as is the case of the Tic-Tac project , and we are witnessing a growing interest in the methodologies of using Cell phones in the classroom – in the absence of computers and Wi-Fi -, in the Global North or in the most developed urban areas of our planet, it expands, from the smallest gestures – such as lighting a lamp, driving a bus, asking for a taxi or find a partner on social networks – the Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence (AI).

It is very likely that the jobs of the future will be found in companies of digital technology and artificial intelligence and that their success will lead us to levels of productivity and, at the same time, unprecedented automation and lumpenization.

The paradoxical prophecy of the future says that fewer employees will be needed, but unemployment and the accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few will grow. Given this scenario in which the automaton machine will be part of the revolution so far faster, massive and at the same time unequal, would the help of the Humanities be useful?

The question is almost impossible to answer, but I’m interested in stopping here in a place of reflection at the crossroads of the Humanities – in both human sciences – and technology.

God’s finger

For that, first of all, I am going to tell a brief story: before 1950 an Italian Jesuit priest named Roberto Busa had finished his doctoral thesis on the work of Santo Tomás de Aquino and was interested in making a text of his texts, something like that Like a great glossary.

Given the enormity of this textual corpus, Busa understood that the titanic task could not be carried out from the human and decided to get in touch with the IBM company, which at that time had begun to venture into the field of computational linguistics. From that crossing came what is considered the project that gave rise to what we now call Digital Humanities: the Thomisticus Index, today Corpus Thomisticum .

The analytical and quantitative work of Busa and his team on more than 22 million words in 23 different languages and nine alphabets was such a work that the Jesuit summed it up, as a good believer, in these three words that refer to the digit, which It can be both the machine and the human: “Digitus Dei est hic!” (God’s finger is here!)

Today the Digital Humanities are an increasingly entrenched field in the field of scientific research and university education and, in a nutshell and, bridging the Busa project, they still seek to explore the most diverse corpus with digital tools: texts old or modern, already digitized or in process, images, sound ..

The critical view of the humanities

Through the use of a certain digital resource, the Digital Humanities undermine those corpus and seek to see knowledge beyond the text, moving from the data to the text or the work. In their practice – because if there is something that defines them, it is practice – they also teach us to be critical. Critics because we can get into the guts of the texts and because to practice them before we have to think about technology: not all tools serve the same; They are not all the same either. It is not the same to work with software that is purchased – or proprietary – than to do it with free and free technologies.

Although digital humanities are not positioned on one side or the other, they open the door for us to choose the way in which we want to share our knowledge. They also teach us to be critical because the Digital Humanities, at that intersection they propose, make the Humanities a group work space. In the Digital Humanities project we can investigate together with our peers, but also with the help of programmers, computer linguists, librarians; We learn from and with others.

Thus, if the technological-social evolution that we are approaching seems to be somewhat dehumanized, at least one shared critical view can always help. Let us then approach it from the digital Humanities.

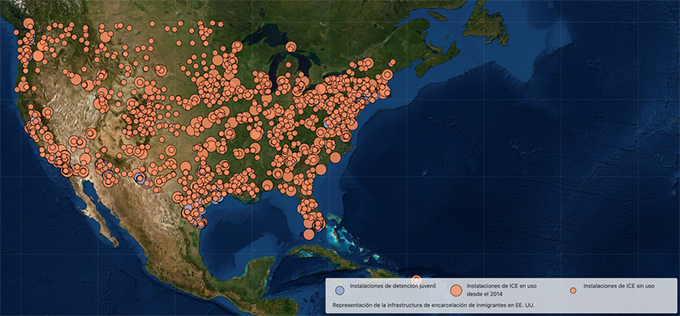

In 2018, the new zero-tolerance immigration policies of the United States government had separated more than 2,300 children from their families . Alex Gil, a digital humanist and librarian at Columbia University, knew that his daily work – helping people find information in the library using technology – could collaborate. Together with the historian Manan Ahmed and a large group of collaborators from the most diverse disciplinary branches, they installed a chat on Telegram, shared a spreadsheet and began to look for data available in open and public form – government immigration records, tax forms , job listings, Facebook pages — in order to locate and identify detention centers where children could be housed.

The result of this research is the Torn Apart / Separados interactive site and project , in which, thanks to the structuring and mining of these data available on the Web, we see the enormous migratory enforcement apparatus dispersed on a digital map in the States. United, approaching the possible shelters where children could be staying.

Torn Apart / Separated. xpMethod, Borderlands Archives Cartography, Linda Rodriguez, Merisa Martinez and Moacir P. de Sá Pereira

Minority women

Using the social network Twitter, Jennifer Isasi , a specialist in data curation, showed in several tweets and through different visualizations of graphs how in the universe of literary awards women remain a minority although, paradoxically, the data indicated that a large group of authors had been awarded several times.

A final example: some time ago with my research group we started working on the annotation, mapping and digital edition of an Argentine chronological text of the early seventeenth century called History of the conquest of the Río de la Plata – or handwritten Argentina , as it is most commonly named – a text that, in the words of the historian María Juliana Gandini, can be defined as a “brutal clash of worlds”: that of the overseas expansion of early-modern Spain with Guaraní agrarian societies.

From the close reading, what we humans do about the texts, the first thing that emerges is this clash of cultures that is read in History of the conquest of the Río de la Plata and, in parallel, meat is made in the figure of its author , Ruy Diaz de Guzman , son of an Indian Guarani and the strongman of the region, Domingo de Irala, and also relative of Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca. However, distant and quantitative reading reveals data that goes unnoticed. One of them is the term “Indians”, which is not only almost as central as the term “land” or “river”, but it is the one that dialogues with the most words in the story. The Indians bring together and make sense of the story without being the “protagonists” of the chronicle.

The human look

Nothing that the digital Humanities show us is completely unknown to us, however, the differential element that they bring is to allow us to see beyond the human reception of texts or images. Here are the data – massive, hidden or intuited – that emerge and dialogue with the texts and with us through technology, but that through our human gaze build meaning.

In the Digital Humanities projects, unlike what happens with the reading of a book or an article, we no longer passively receive the knowledge of a specialist but we assume it, at the same time, in an active role: we interact with the keyboard and the screen and with the data or the corpus that are shown to us and, through them, we build our own knowledge or simply ask ourselves questions.

Even knowing that neither technology nor science are divided equally in our world and, therefore, neither the research in digital Humanities, the critical look and the construction of knowledge with technological tools that they bring are a good example to better understand the past and the present and, why not, the future.

A human look at the machines that he does not seek to answer, as in the Turing Test all the questions, but at least he can know, as the magnificent Úrsula K. Le Guin said , what are the impossible questions to answer.

Author Bio: Gimena del Río Riande is a Researcher at Institute of Bibliographic Research and Textual Criticism, CONICET