Multiple times a year I provide impact statement workshops. Not everyone can make those, so rather than having that knowledge only live in the workshop space, I thought I’d highlight some of the main take-aways shared during that workshop here.

While I’m based in Australia and tailor a lot of my advice to Australian frameworks, this post has relevance for any researcher who is trying to write a research impact statement. If you’re not sure what is meant by research impact, my earlier post about the emerging impact landscape may be helpful.

Increasingly, impact statements are integrated into funding applications. The impact statement should be a standalone snapshot of your project. Impact statements may go by other names — for example, the Australian Research Council’s National Interest Test could be considered an impact statement — but they are essentially asking researchers to provide the same components.

Impact statements are a genre of writing and, once you have a handle on the components that make up a persuasive impact statement, they’re much less daunting to generate.

Types of impact statements

Retrospective — the impact, and how it was generated, from a previous project

Prospective — what you’re planning to do to generate impact for a proposed project

It’s important that you know what your funder is asking for. Some funders want to ensure that you have a firm plan in place to generate impact for a proposed project. Others want proof that you know how to generate impact because you have in the past.

Both retrospective and prospective impact statements have the same components; the tense is just different (e.g., “we did” vs. “we will”). To simplify things a little, we’ll stick with prospective impact for statements for the rest of the post.

Impact Statement Components

At the simplest level, there are five components that make a strong impact statement: problem, solution, beneficiaries, outputs, and impact.

PROBLEM

The problem statement needs to be high-level, clear, and simply stated. This is the ‘why’ of the research, not just the ‘what’. Problem statements can be stated in the negative (e.g. “childhood obesity is an epidemic”) or as a positive (e.g. “our project will reduce childhood obesity”). In the latter, the reviewer fills in the gap and goes, “Ah yeah, this is a project about childhood obesity.” If you’re having difficulties getting started, ask yourself, “Why is my research needed?”. Pretend you’re explaining it to someone you meet around a campfire or at a barbeque.

This section tends to pose the greatest challenge to researchers when crafting a persuasive impact statement. My suspicion is that researchers know too much about their topic and have difficulty articulating succinctly what the problem is for a generalist audience. Remember, expert reviewers are experts in their subject, not always yours.

SOLUTION

In this section, you talk about your proposed solution to the problem. This is where you discuss the research you want to do. Remember to align your proposed solution to the problem statement. There should be a cause and effect relationship here — because this thing is an issue, we’re going to do this. Some grants have multipage impact statements but usually it’s a fairly small space so keep it short, succinct, and high-level.

An issue I often see with this section is that researchers rehash what they have written in other sections of the application. Don’t copy and paste. Start fresh and try not to get too bogged down in the details. You might mention that you will use interviews, but you don’t need to delve into sampling criteria, which generally belongs elsewhere.

BENEFICIARIES

Reviewers want to know that you have a clear sense of who is going to be interested in using your research findings. The more concrete your beneficiaries can be, the better. If you can name project partners, name them. If you can say how they will be involved in the project, do.

Saying that your research will benefit the public won’t cut it. It’s just too vague. Indicating that your work, for example, “will benefit young males between the ages of 18-25 by working with x, y, and z organisations,” is much more persuasive.

OUTPUTS

Outputs could be anything; a website, educational resource, videos, pamphlets, workshops, etc. The outputs are how you will get from research results to impact. Impact doesn’t just magically happen so lead the reader on a journey of how you’ll work with beneficiaries and stakeholders to make it happen.

This is another area that researchers seem to struggle with or haven’t though through fully. I suspect it’s because outputs happen after research results so it’s sometimes difficult to conceptualise what forms the outputs may take. Be that as it may, reviewers want to know that you’ve thought through how you will mobilise results into practice.

IMPACT

Often, the stated impact is only a sentence or two. It’s what all your activities will ideally culminate in. It could be an impact on policy, culture, health/wellness, the environment, and/or the economy. If your research is adopted into practice, what will that look like? What will the impact be?

Again, compelling specificity is the key. Lines like, “the impact will be on policy by working with policymakers” are anaemic and won’t convince reviewers that you have a clear sense of how to generate impact. What policymakers are you going to work with? What policy are you looking to impact? There are many posts about impact and policy, including Analysts, advocates and applicators, From science to action, and The hard labour of connecting research to policy during COVID-19.

Putting it Together

In my workshops, I ask people to explain the elements of their impact statements and have others paraphrase it back. Often, when people hear the ways people interpret what they said, they find gaps in logic and issues with clarity.

You can do this exercise yourself as well. Pick up your phone, go to the memo app, and press record. Talk through, to yourself, each of the above impact statement components. Then go for a walk and listen to yourself. Listen a few times and you’ll start to hear where there are jumps in logic, where you have used jargon, where a reviewer might raise their eyebrows.

Write each of the sections above separately — one paragraph each — then stitch it together.

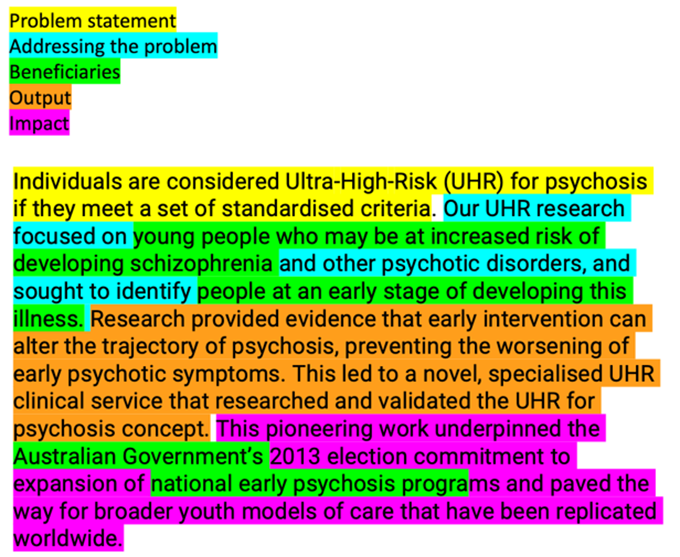

For my workshop, I invite participants to colour-code the impact statement components for their research.

Here’s a marked up example of text from the engagement and impact submission of this study about reforming youth mental health interventions:

You want to ensure that there’s a reasonable balance between each of the sections.

If 90% of the statement is the problem, or the solution, or the outputs, it’s out of balance. You need to make sure that each component is adequately addressed.

My top tips for creating a great impact statement:

- Don’t leave it until the end. The impact statement should be the first part of a grant you write, not the last.

- Know your audience. Who is reviewing your statement?

- Don’t oversell or undersell yourself. Reviewers are savvy.

- Watch for jargon! Expert panellists are only experts in their area.

- Don’t undersell your engagement work in the community, industry, etc. Engagement can lead to impact.

- Name your stakeholders if possible.

- Record yourself outlining your project. Then write it out. This can give you a quick start on your impact statement.

- Engage someone who’s not in your discipline to review your statement.

- Don’t be too precious with it. It’s a high level statement that can’t address every nuance of your project.

Author Bio: Dr Wade Kelly is the Executive Advisor, Research Impact, at La Trobe University, in Melbourne, Australia.