Publishers often send me academic writing books to review. I happily look through every book, but if I think I can’t wholeheartedly recommend it, I just don’t write a review. I don’t want to crush a fellow author’s soul. The rejected titles sit sadly, in small piles of guilt, on the bottom of one of my bookshelves.

Recently, during an office clean up, I picked up Eric Hayot’s book “The elements of academic style”, which was sent to me by the publisher, Columbia University Press, way back in 2014. On the strength of our recent book “How to fix your academic writing trouble”, Katherine, Shaun and I have been offered a contract to write a new book aimed at undergraduates (tentatively titled ‘Level up your Essays’). So instead of just refiling it on the reject shelf, I had a lazy flip through to see if there was anything useful. I’m ashamed to admit I totally failed to recognise what a gem “The elements of academic style” when I first looked at it. Talk about missing out all these years! Thankfully, you can still pick up copies of the book online, so here is my very belated review.

The full title of this book is “The elements of academic style: writing for the humanities”, which is one reason why it ended up in my rejection pile in the first place. I try to provide writing advice that is suitable for all disciplines, and this book is unapologetically aimed at literary studies PhD scholars. While I respect this laser-like focus, I think it’s a bit of a pity that science students or even people in other humanities disciplines like Social Science, probably won’t pick it up. A lot of the advice Hayot offers will work for anyone, most especially his concept of the ‘Uneven U’: absolutely breakthrough advice for structuring paragraphs.

Hayot’s Uneven U is a different take on the generic advice that is given to structure a paragraph, namely that one should start with a Topic sentence, then an explanation, example, analysis and summary. This standard paragraph formula is sometimes called TEXAS or TEEL (topic, evidence, explain, link). I’ve been teaching the TEXAS/TEEL method for years to great effect. It surprises me how often PhD students benefit from this elementary advice, but sometimes simple rules of thumb create useful clarity in the middle of a complex writing project. The problem with TEXAS is that it can make your writing quite repetitive. Not every paragraph needs all the elements of the TEXAS formula, which is why it doesn’t work all that well for introductions and conclusions (which require much more summery than paragraphs in the middle sections). Hayot’s Uneven U is the sophisticated, cocktail version of TEXAS and, I think, much more flexible and useful.

Hayot starts by claiming there are five types of sentences in argumentative writing and they can be thought about as being different conceptual levels (here I quote from page 60 of Hayot’s book):

Level five: Abstract; general, oriented toward a solution or conclusion

Level Four: Less general; orientated toward a problem; pulls ideas together

Level Three: Conceptual summary; draws together two or more pieces of evidence, or introduces a broad example.

Level Two: Description; plain or interpretive summary; establishing shot

Level One: Concrete; evidentiary; raw; unmediated data or information

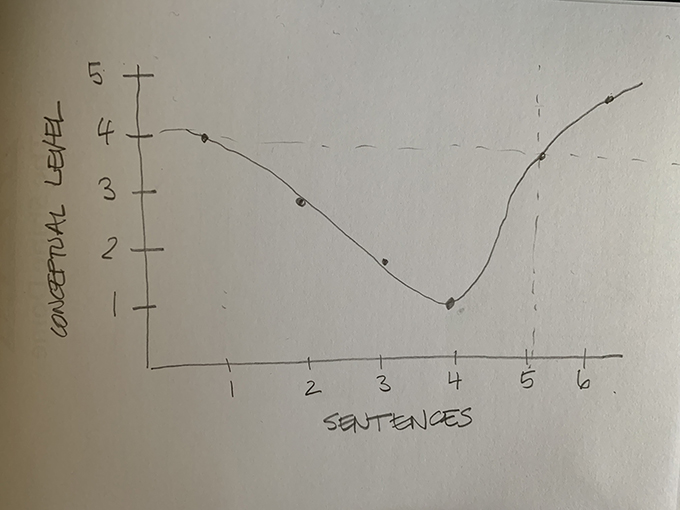

Hayot suggests that your paragraphs should have an ‘uneven U’ structure, starting at statements that are level 4, going down as far as level 1, then ending at level 5. On a graph it looks like this:

A topic sentence doesn’t have to be a grand, sweeping statement as the TEXAS formula suggests, but a tight, problem-focussed starter. Save the grand sweeping statement for the end of the paragraph instead. The idea of sentences having conceptual levels frees you up from thinking that sentences have to be complex to ‘work’. I am always trying to ‘fancy up’ level one sentences, but since I started using this method I don’t bother, and honestly, they are much stronger.

I’ve been using this advice for a couple of months on my own writing and on others, and it works remarkably well. It’s hard to explain precisely how it works, so let’s look at a worked example. Here’s a paragraph from our most recently published paper “A Machine Learning Analysis of the Non- academic Employment Opportunities for PhD Graduates in Australia” :

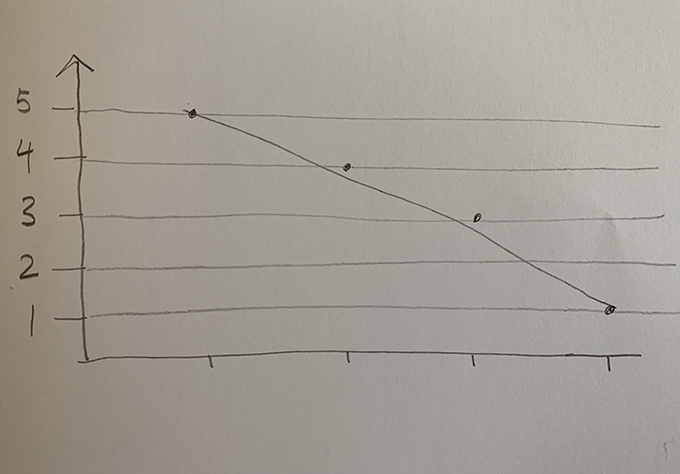

The PhD was initially designed to train the next generation of academics, but this career outcome is looking less likely for today’s graduates (level 5). There have been claims that there is an over-supply of graduates for academic positions over the last decade at least (Coates and Goedegebuure, 2010; Edwards, 2010; Group of Eight, 2013) (level 4). The latest Australian data, showcased in the Australian Council of Learned Academies (ACOLA) report (McGagh et al., 2016), suggest that 60% of Australia’s PhD graduates will not end up in academia, a finding consistent with other advanced economies (level 3). For example, a recent survey by the Vitae organisation (2013) in the UK showed that although the overall unemployment rate for PhD graduates was low (around 2%), only 38% of PhD graduates are now employed in academia after graduation. (level 1)

Mapped with Hayot’s method, it would look like this:

Yikes! Let’s fix it with the Uneven U method. To begin, I took the first sentence – which was level five – and made it the last one. I then reparsed the new first sentence to make it into a stronger topic sentence and created a new, second sentence pitched at level three. I turned the next level three sentence into a level two sentence and left the level one sentence alone. After that, I added another level three sentence and altered the final (which used to be the first sentence) to make it more clearly a level five. Here’s the result:

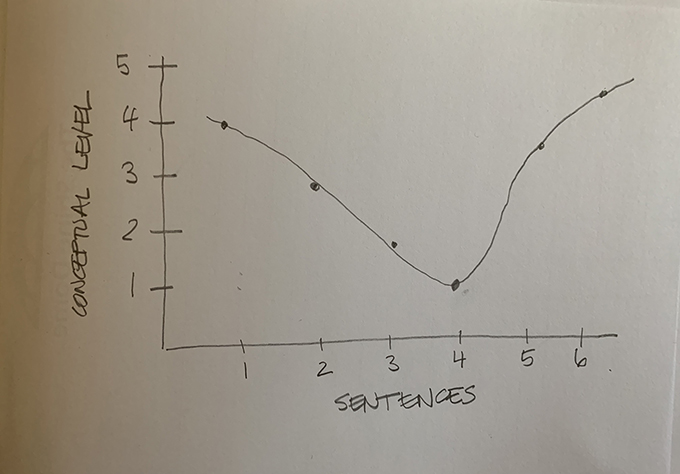

For more than a decade, scholars of higher education have claimed that there is an over-supply of graduates for academic positions (Coates and Goedegebuure, 2010; Edwards, 2010; Group of Eight, 2013) (level 4). If this oversupply problem is real, we should see more PhD graduates making a rational decision to leave academia at the end of their degree and statistics seem to be bearing out this trend (level 3). The latest Australian data suggest that 60% of Australia’s PhD graduates will not end up in academia, a finding consistent with other advanced economies (McGagh et al., 2016) (level 2). For example, a recent survey by the Vitae organisation (2013) in the UK showed that although the overall unemployment rate for PhD graduates was low (around 2%), only 38% of PhD graduates are now employed in academia after graduation. (level 1). If more PhD graduates are looking to leave academia, we must ask: does the PhD need to change? (level 4). Since the PhD was initially designed to train the next generation of academics, this change may be dramatic, with far-reaching consequences for candidates, supervisors and institutions (level 5).

When I map it again, the paragraph now looks like this:

I think you’ll agree the ‘tone’ sounds much more argumentative and there is also a sense of momentum that was missing in the first attempt (I really wish they would let you edit a published paper!). I’ve always struggled with the last sentence in each paragraph; the idea of doing a ‘summary’ sentence is not that helpful. My final sentences have always ended up being a bit wishy-washy and vague, now they are where some of the most provocative thinking happens, encouraging the reader to keep on reading.

The Uneven U concept also helps me help students who write paragraphs that lack ‘meat’. When I map the paragraphs that are hard to read I usually find the student is hovering around level three and needs to ‘land’ somewhere more concrete in the middle to give the paragraph more impact. The neat thing about the Hayot method is that you don’t have to go all the way down to level one: it might be enough to take a level three sentence and bang it down to level two.

I hope you have enough here to try the Hayot method for yourself: on your paragraphs at least. Hayot extends the theory to structuring subsections and even a whole work, which is a really mind-expanding read. However, it would take me an entire book to explain how the Uneven U helps you write a whole dissertation, and Hayot has done it already so check out “The elements of academic style” for yourself. The book is still available in paperback and a reasonably priced Kindle version. Be warned: it’s rather densely written and definitely not for beginners. People who are not literature scholars may want to skip some sections, but I think anyone serious about improving their writing to the ‘cocktail party’ level will find this book invaluable.

What do you think of the Uneven U? I found once I understood the concept, I started seeing it everywhere – or noticing the lack! Did I explain it properly, or do you need more information? Feel free to ask questions in the comments.