Canadian media have reported on concerns that due to pandemic school closures students are falling behind in learning, and specifically in reading. Research from Alberta examined reading test scores from this past September against earlier years and found grades 2 and 3 students scored consistently lower.

Teachers have fewer opportunities to work individually with children who are struggling in online settings. In many classrooms, health guidance recommends avoiding sharing classroom supplies. This means teachers have removed books that children would normally browse and borrow, so children have limited reading material when they attend classes in person.

Family members who want to prevent children from falling behind in reading do not have to use expensive resources or ask children to do tedious exercises. Parents’ and other family members’ involvement in encouraging children’s reading and writing in everyday play and family life can make a difference to their children’s later literacy achievement: this is the case regardless of a family’s socio-economic status and prior education.

Creating messages

Research from the Northern Oral language and Writing through Play (NOW Play) project offers motivational alternatives to using phonics exercise sheets that parents often seek out to get their children started with writing and reading.

Researchers widely agree that reading with children at home supports children’s vocabulary development and listening comprehension — two factors that correlate highly with reading comprehension. However, the important contributions of writing to children’s reading are not often recognized beyond research circles.

In the NOW Play project, children aged four to six years old create messages to people they know through drawing, scribbling and writing letters and words. Teachers and parents can help children with their writing by showing interest in the writing that their children initiate, demonstrating how to form letters and slowly voicing individual sounds in words that children want to write.

This helps children recognize the sounds in words. It also models a writing practice they can use when writing independently. Participating teachers have noted children’s excitement about reading and writing, and have been very pleased with children’s progress as a result of this dual focus.

The purpose of print and play

Settings where children can see how print is useful for carrying out activities that are important to them are ideal for supporting reading and writing.

Imaginary play about going grocery shopping, for example, offers many opportunities for children to read and write, and learn new vocabulary.

Piper, a five-year-old girl in a northern Alberta kindergarten that is part of the NOW Play research project, wrote her grocery list while playing grocery store. Before going to the pretend store, she sounded out the words apple, tomato and pizza, writing sounds she heard (in this case, sounds for each word’s first letter) in each word.

Piper then picked up her grocery list and announced, “Let’s go shopping!” When asked what was on her list, she read the letters as if she were reading the full words for each item.

Grocery store play offers many other opportunities for reading and writing. While stocking pretend grocery store shelves with boxes and cans of food items, young children and their teachers or early childhood educators can read the labels together. They might make up a name for the grocery store and write a sign for the store.

With family, at home

Families can apply these research insights in the home. Parents and other family members might take up roles that introduce new vocabulary about grocery store shopping, food items or people who work in grocery stores. As they learn new words in the grocery store context, children develop a broader vocabulary to help them with their reading.

Young children learn how to sound out words and write letters when they write messages back and forth with others. Children can also learn new vocabulary from family members’ messages, and can try out the new words in their own writing.

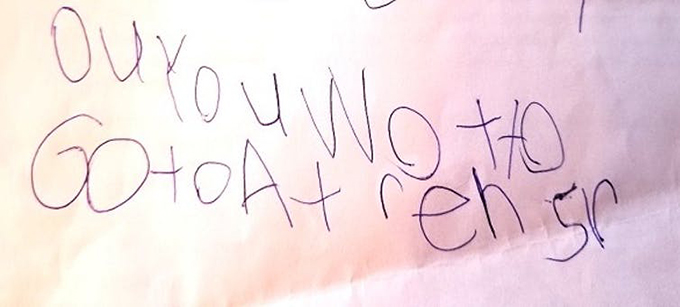

Do you want to go on a treasure hunt?’ note by five-year-old Emme. (Shelley Stagg Peterson), Author provided

When older family members join the play, they can become spontaneous reading and writing teachers, where young children read notes and write different kinds of messages that fit with the pretend situation.

I tried this with five-year-old Emme. She, her nine-year-old sister, Leah, and I played a treasure hunt game together. With the two girls taking turns, one child and I wrote clues to lead the other to a treasure. Emme later wrote a self-initiated note with little help, except that I slowly stretched out the sound of treasure. Emme then read the note aloud to be sure that Leah and I understood what it said.

Value of writing in daily life

Parents and supportive adult family members in children’s lives are in an excellent position to follow what kindergarten teachers in the NOW Play project did to teach phonics and letter writing while teaching the value of writing and reading in daily life.

At a time when many families are together for extended periods of time, play-based writing activities are a meaningful and effective way for parents to provide important foundations for their children’s literacy.

Author Bio: Shelley Stagg Peterson is Professor of Elementary Literacy, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning at the University of Toronto