After surveying over 3,000 students about kindness, I learned a lot about how children and teens understand and practice this quality, especially in school. The results may surprise parents and educators.

Researchers have extensively studied the effects of kindness on the well-being of individuals. They found that acts of kindness such as paying something to a stranger, counting the number of acts of kindness done each week , and acting kindly to people around you are factors that contribute to well-being.

When I first started studying kindness as an education researcher at the University of British Columbia, I noticed that there were no measures available to assess perceptions of kindness in school. We also knew very little about how children understand kindness and show it.

Measuring and defining goodness

My foray into understanding goodness began by seeking to measure it. I teamed up with two colleagues, Anne M. Gadermann, an expert in social determinants of health, and Kimberly A. Schonert-Reichl, an applied developmental psychologist. With them, I developed the kindness scale at school .

Using a five-point scale, I surveyed 1,753 students in late elementary to early high school about how often kindness showed up in their school and to what extent it was encouraged and modeled by teachers and other stakeholders in the school environment.

The results of this study revealed gender differences in perceptions of kindness at school , with girls having higher perceptions of kindness at school than boys.

We also noted a negative trend: students perceive their school as being less and less “friendly” from the end of primary to the beginning of secondary school. This phenomenon coincides with the findings of Canadian and Italian researchers who found a decrease in prosocial behavior from childhood through adolescence and that students become less connected to school as they move from childhood to adolescence. adolescence .

Along with graduate student researcher Holli-Annie Passmore, I also wanted to explore children’s understanding of kindness .

Children who measured kindness on the five-point scale also answered a series of open-ended questions about kindness such as, “What does it mean to be kind?” and “Can you give an example of an act of kindness you did at school?”

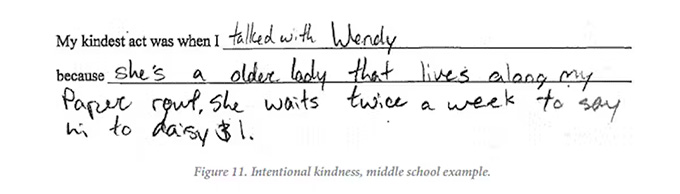

I spoke with Wendy because she is an older lady who lives on the way to school. She waits for us twice a week to say hello to Daisy and me. (John-Tyler Bifnet) , Author provided

We found that three themes accounted for around 68% of all responses: helping (around 33%), showing respect (around 24%), and encouraging or defending (around 11%).

What does kindness look like

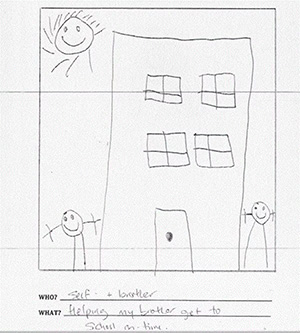

Since there are very few studies done with young children, I asked hundreds of five- to eight-year-old students what kindness looked like and illustrated it with a drawing of them doing something nice at school.

This “drawing-testimony” methodology has revealed rich examples of the kindness of young students. I found that the dominant themes of kindness in young children included helping physically, helping emotionally, and sharing. Based on a study of 112 children’s drawings, I proposed that kindness, from the perspective of young children, is an “act of emotional or physical support that helps establish or maintain relationships with others.

I also asked the young children what they thought of the kindness of the teachers. This opened up new avenues in kindness research and opened a window into student-teacher relationships. Surprisingly, when more than 650 children from kindergarten to grade three were asked to illustrate the kindness of a teacher , nearly three-quarters drew a picture of a teacher…teaching.

What was also interesting is that the students draw teachers who help a classmate – a peer – in the classroom. This observation reinforced the fact that the students are very attentive. Teaching classmates is seen as kindness on the part of teachers.

This finding should help educators better understand how to build positive relationships with students. It’s not so much school trips, guest speakers and special events that encourage students to describe their teacher as nice. From the perspective of young children, teachers are kind when they teach.

The quiet kindness

Based on this study and others mentioned above, it became clear that children and adolescents practice kindness in a variety of ways, falling into at least three distinct categories .

Most people are familiar with “random” kindness, more aptly called “reactive” kindness, or kindness where we respond to a perceived need for physical or emotional support.

Most people are familiar with “random” kindness, more aptly called “reactive” kindness, or kindness where we respond to a perceived need for physical or emotional support.

The second category is what I call “intentional kindness,” kindness planned, thought out, and offered to meet a person’s physical, social, or emotional needs.

The final way children and adolescents exemplify kindness is through what I call “quiet kindness,” a socially and emotionally sophisticated kindness that only the initiator knows. This category of kindness requires empathy and a low need for recognition or reinforcement.

Further research is needed to determine to what extent the types of gestures of children and adolescents fall into these categories and whether there are any benefits to well-being from practicing different types of kindness.

Encourage intentional kindness

It was not easy for all students to define and model kind gestures, and some students needed help to be kind. So I developed a model to encourage intentional kindness in the classroom . Students must first identify people in need of kindness, then follow a step-by-step guide to planning an act of kindness for others. This includes deciding if the act will be driven by time and effort (like shoveling someone’s driveway) or if it will require materials (like making someone a gift basket ).

Educators and parents are in a good position to create the conditions that encourage children and adolescents to be kind. Doing so helps to create learning communities that foster optimal peer relationships, healthy student-teacher relationships, and a caring school environment.

Author Bio: John Tyler Binfet is Associate Professor, Faculty of Education at the University of British Columbia