Adults have been writing for children for centuries. Among the different forms that these publications have taken, there are few that can seem entertaining to us today. Indeed, the works intended for the youngest aimed above all at their moral and spiritual progress.

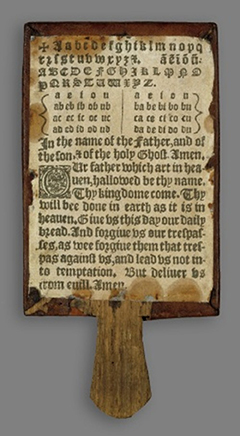

Children in the Middle Ages learned to read on wooden tablets covered with parchment containing the alphabet and a basic prayer, usually the Our Father. In the English-speaking world, later versions of these tablets are known as “hornbooks” (from “horn”, horn and “book”, book), because they were protected by a thin protective layer of horn.

A 1630 horn book. Folger Digital Image 3304 , CC BY-SA

In the XVII th century were published books on spirituality specifically for children. The Puritan Reverend John Cotton designed a children’s catechism in 1646 called Milk for Babes , and republished in 1656 in New England as Spiritual Milk for Boston Babes . It contains 64 questions and answers relating to religious doctrine, beliefs, morals and good manners. James Janeway (also a Puritan minister) collected stories about the righteous life and death of godly children in A Token for Children (1671), prompting parents, nurses and teachers to have the book read “over a hundred times” .

These stories of children on their deathbed may not have much appeal to modern readers, but they are important testimonies to how the question of salvation was viewed and children were put first. plan. Medieval legends about Christian martyrs, like Saint Catherine and Saint Pelagius, are of the same order.

Other books were about good manners. Erasmus wrote a famous Latin manners manual “for the use of children” (1530) which gives them many tips, such as “Do not wipe your nose on your sleeve”, “If you move on your chair , by sitting on one buttock then on the other, you will give the impression that you are farting. So make sure your body stays upright and well balanced ”. This statement shows how physical behavior was viewed as a reflection of moral virtue.

In a society where reading aloud was common practice, children were also likely to be part of the audience who listened to romance novels and secular poetry. Some manuscripts therefore included courteous poems explicitly intended for young children, alongside romances, legends of saints, and short moral and comic tales.

Do children have a story?

Much has been written about the debate over whether children have had distinct needs in the past. Medievalist Philippe Ariès suggested in L’Enfant et la vie familial sous l’Ancien Régime that children were seen as adults in miniature because they were dressed the same way as them and their routines and learning were completely turned to their future roles.

But there is plenty of evidence that children’s social and emotional (as well as spiritual) development has received adult attention in the past. The regulations in force in the schools of the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of Modern times show that it was understood that children had to be given time for play and imagination.

Archaeologists working on school sites in the Netherlands discovered traces of games that children played without adult intervention and without trying to look like them. Some authors on education suggested that learning should be made fun. This progressive vision of child development is often attributed to John Locke, but she has a previous history if we examine the educational theories of the XVI th century and even before.

Archaeologists working on school sites in the Netherlands discovered traces of games that children played without adult intervention and without trying to look like them. Some authors on education suggested that learning should be made fun. This progressive vision of child development is often attributed to John Locke, but she has a previous history if we examine the educational theories of the XVI th century and even before.

Some of the more imaginative genres we now associate with childhood actually appeared in a whole different context. In Paris in the 1690s, the salon of Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, baroness of Aulnoy, brought together intellectuals and members of the nobility.

There, the Baroness would tell fairy tales , under which satirises of the royal court were concealed, with a sizeable proportion of commentary on how society worked (or did not) for women of that time. These stories mingled folklore, current events, popular games, contemporary novels and ancient romantic tales.

It was a way of presenting subversive ideas, under the guise of fiction. Novels of the XIX th century that we today associate the children were in fact sharp observations of political and intellectual contemporary issues. One of the best known examples is the book of the Reverend Charles Kingsley published in 1863 – The Water Babies: symbolic tale ( The Water Babies: In Fairy Tale for a Land Baby ) – a satire against child labor and a critique of contemporary science.

The moral of the story

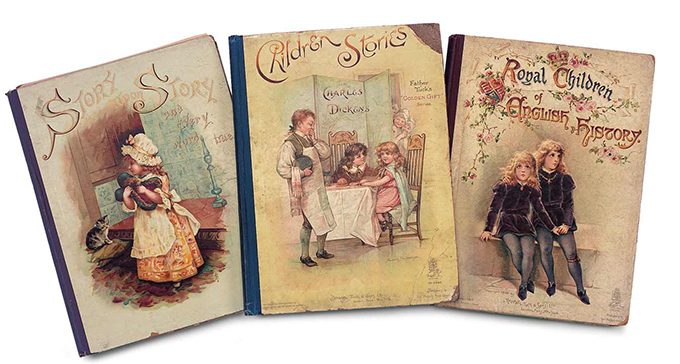

In the XVIII th century children’s literature had become a commercially viable sector for the London press. The market was primarily fueled by publisher John Newbery, the “father” of children’s literature. As the literacy rate increases, the demand for educational materials continues. It is also becoming easier at this time to print images, which may appeal to young readers.

THE XIX th century, more and more children’s books are printed and moral elements are still very present. Katy’s development of patience and neatness, for example, is essential in Susan Coolidge’s book What Katy Did , while fiery and outspoken Judy is slain in Ethel Turner’s book Seven Little Australians. Some authors have succeeded in combining a sense of the comic and a lesson in life, such as Pierre the tousled or Crasse-Tignasse ( Der Struwwelpeter , in German) by Heinrich Hoffmann.

At the turn of XX th century saw the emergence of a true literature for children, where children discover serious subjects, with or without the help of adults, and often in a fancy setting. Works by Lewis Carroll, Robert Louis Stevenson, Mark Twain, Francis Hodgson Burnett, Edith Nesbit, JM Barrie, Frank L Baum, Astrid Lindgren, Enid Blyton, CS Lewis, Roald Dahl and JK Rowling fall in this vein.

Children’s books always contain moral lessons. They continue to acculturate the new generation to the beliefs and values of society. This does not mean that we want our children to become wizards, but we want them to be brave like the wizards whose adventures they read, to defend each other and to develop a set of values. particular.

We tend to think of children’s literature as providing imaginative spaces for children, but we are often short-sighted in the face of the genre’s long didactic history. And as historians, we continue to seek to know more about the autonomy of children of the premodern era, in order to better understand in which spaces they could deploy their imagination, beyond the books that were offered to them. to learn to pray.

Author Bios: Susan Broomhall is a Professor of History, Joanne McEwan is a Researcher and Stephanie Tarbin is a Lecturer in medieval and early modern history all at the University of Western Australia