So, 2020 hey? What a trip. I don’t know about you, but concentrating on my work when the world feels like it’s up in flames, literally and figuratively, has been, well – difficult. In order to keep my shit together in front of students and co-workers I’ve been, as a Japanese theme park put it, screaming inside my heart:

But let’s be honest: research is always difficult. It never ever goes quite to plan. In fact, research projects seem to actively resist careful planning attempts.

I’m considered quite an effective and productive researcher, yet no project I have ever managed has unfolded as I expected. I generally deliver on time – and by that, I mean about a month or so past when I promised to deliver – but it’s always a mad rush to the finish line. I’ve thrown every planning trick in the project management book at this problem over the last 20 years. Despite my best efforts, all my projects go over time, head off in a different direction or deliver outcomes I wasn’t expecting.

I know I am not alone. Most PhD candidates take around 5 years, not 3.5 years, to finish their degree. Only about 20% of people finish ‘on time’ at ANU – and our students are not unusually tardy. You might be over time on your PhD right now – despite working hard for years and years. It’s not just PhDs that don’t go to plan: try participating in an edited book project. I handed in the last chapter I wrote on time – and by that I mean about a month past due – and the editors thanked me for being the first to deliver. That was 18 months ago. I’ve heard nothing since about the publication of said book. I imagine they are still waiting for the other chapters.

Why are academics so chronically late delivering on projects?

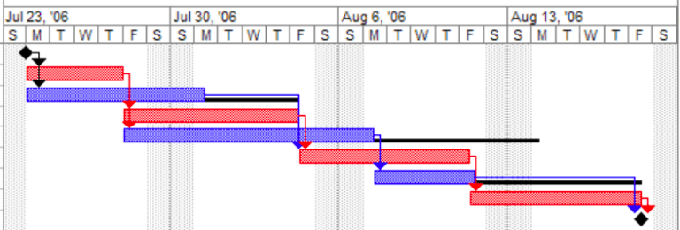

Lack of training probably has something to do with it. I guess the university assumes that, by the time you get to a PhD, you are an accomplished student who can get shit done. This is a big assumption. My disciplinary background, way back when, was architecture. You’d think they would teach project management somewhere in a five year undergraduate course on delivering buildings, but sadly I can report – not so much. I did, however, pick up a lot of project management techniques in the 10 years or so I spent hanging around in architects’ offices. I learned, for instance, about Gantt charts for visualising individual tasks on a timeline of a project. A Gantt chart looks something like this:

You’ve probably made one or two of these – we love asking PhD students to make Gantt charts at regular intervals. Grant applications are certainly not complete without the mandatory Gantt chart, which is there to tell funders that you can realistically estimate time for project delivery. Some grant funders look at this first, so it’s important to be able to do a Gantt chart well. If you’re interested, the Research Whisperer folks have a great post on putting a simple gantt chart together.

Gantt charts are great.

Except they don’t work. You know – for the actual managing bit.

A Gantt chart is good for communicating how you think a project will progress, but no Gantt chart survives first contact with twin enemies of task and time. Research work is unpredictable: experiments don’t go to plan, interviews take longer to set up than you think, that archive is only open between May and September… there’s always something. Before too long, that Gantt chart looks hopelessly optimistic in terms of time on task, so you abandon it and just keep soldiering on. At some point, you will have to report on progress, so you pull out the old Gantt chart to compare your progress with what you said you would do. Old Gantt charts are quaint aren’t they? Full of tasks that you thought needed to be done that no longer seem important and – more importantly – empty of the tasks that actually turned out to be worthwhile.

Good project management is at the heart of being a good academic researcher. I’ve bought a LOT of project management books and invested in a lot of software, which has helped a bit, but failed to solve the lateness problem completely. Lately I have switched away from a focus on tools and started to try and understand the problem of lateness better instead. For a recent episode of our podcast ‘On the Reg’ I did a deep dive into the project management literature (ok, I googled ‘why doesn’t project management work?’ and followed my nose through the most interesting papers that came up). Through the magic of Google scholar citation searches, I came across one particularly useful paper with the rather dull title of ‘A framework for project management under uncertainty‘ written in 2002 by Meyer, Pich and Loch (which would be a good name for a Blues cover band).

I felt very seen by this paper; the authors seemed to really understand the nature of my everyday struggle with project management. Meyer, Pich and Loch start by clarifying the difference between projects and processes. Processes are ‘the systematic execution of repetitive activities ’. In the academic world, teaching preparation is a process. Ok, you prepare different kinds of classes, but all teaching preparation has standard steps. You must pull together background material, craft lectures or videos, write content, design activities and align the assessment to your stated learning outcomes (streamlining your teaching preparation by treating it AS a process seems like a good idea, but that’s a post for another time).

A project, the authors argue, is ‘the one-time execution of more or less unique activities’. They point out there are two main strands of activity in any project: (i) managing tasks; and (ii) managing stakeholder relationships. Obviously, in a PhD, your supervisor is your main stakeholder, and your tasks are doing experiments, gathering data, making things or whatever. Other stakeholders to consider are the university who has supported the research, the community of scholars in which the research is carried out and the public(s) who might benefit from the research. No research is carried out in a vacuum: everything must be reported eventually, if only informally, so managing and reporting to stakeholders is critical.

Most problems with stakeholders start because research tasks are fraught with uncertainty, which Meyer, Pich and Loch sort into three categories:

- Foreseen uncertainties: tasks that take longer to do, resources not turning up on time etc, etc – in other words, the ordinary everyday stuff that happens to everyone.

- Unforeseen uncertainties: not anticipated, and therefore a “Plan B” has not been formulated. Floods, hailstorms, pandemics, fires… 2020 has been a giant experiential learning program in unforeseen uncertainties.

- Chaotic, or turbulent uncertainty: You’re trying to do something so new that the project plan itself cannot be fully formulated in advance. Everything is in flux and changing throughout the project: both methods and outcomes, even the project questions.

Meyer, Pich and Loch argue that it’s this last form of uncertainty, chaos or turbulent uncertainty, which makes research projects difficult to manage. I see PhD students become unstuck due to chaotic uncertainty All. The. Time. You might set out with a method, and get puzzling results, which sends you back to the drawing board over and over again. Many PhD students they are redesigning the project methods at the same time as doing data gathering and writing work – I know I did. Some people seem doomed to essentially start the project over and over again…

It’s a truth universally acknowledged (but rarely articulated) that many PhD students can only really articulate the research question clearly at the end, once they have answered it. By the time I see some of these people in our thesis bootcamp program they are tired, burned out and convinced they are failing at everything… but really, they have just been dealing with chaos for 3 or 4 years. No wonder they feel exhausted!

There are a number of strategies Meyer, Pich and Loch suggest for dealing with chaotic uncertainty. I have used or recommended all of these strategies myself, so I was pleased to have my ‘homebrew’ solutions validated. Here are a couple:

Ask yourself: where are the information gaps?

Can you get access to a field site, data, tools and so on. There is where finely honed intuition and experience is crucial. We would expect that supervisors are a good source of information on these uncertainties, but make sure you talk to a range of people who have done a similar project before: they will be able to point out the traps for new players.

Try running parallel experiments, lines of inquiries or methods to see which will work.

If you are doing interviews, see if there is some document analysis that you can use to supplement the data – just in case. If you are doing experiments, aim to try multiple small ones before choosing one that has a huge time investment. Make sure you keep good records of these side explorations. There’s nothing more annoying than doing a bunch of stuff that turns out to be useful in retrospect, but you can’t include it in your thesis because you didn’t record them properly or get the right kind of ethics approval.

Understand that research involves iteration and constant learning from feedback .

Expect to do a lot of work that doesn’t end up in the final write up. Doing a lot of what turns out to be redundant work is not a sign of failure, this is just research business as usual.

Recognise that most research projects cannot be fully planned in advance – but planning is still essential.

Planning is a way of testing out how the project parameters you have set up are tracking. Part of this review process is to realise what is not working. Sometimes researchers can fall prey to the sunk cost fallacy and keep going down paths that will make the project run over time. Reviewing your performance is one way to get better at forward estimating time on task. I use the PERT method, which I don’t have time to explain here – have a look at this slide deck from our bootcamp materials where I have some formulas and other tools to help you complete the writing process.

One of the most important insights in the Meyer, Pich and Loch paper is about the stakeholder management piece. As project methods change, so do deliverables and even research questions. Meyer, Pich and Loch describe your role in the project as a kind of entrepreneur; someone who has to ‘sell’ the new project outcomes and directions to stakeholders. This is why it’s vitally important to try to bring your supervisor along on this uncertainty journey.

Ideally you will regularly be reporting to your supervisor(s) on what has happened, and what you did to try and mitigate the problems you encountered. The authors call this the ‘explain the deviance’ method and point out that this approach to stakeholder management won’t work unless there is a high degree of trust and mutual dependence. All good if you are the kind of student who has a chatty coffee with your supervisor every couple of weeks. In fact, I would recommend those coffees even if there is no substantive progress to report. Regular human interaction naturally builds trust and you will need a reservoir of this trust to navigate the rough patches.

If you have a distant, ‘hands off’ supervisor, the sort who only wants to see you every three to six months – or even longer, you’ve obviously got a big stakeholder management problem. It’s hard to build trust with a person you spend no time with. It’s also hard to complain about how you are being treated if no one knows the details of how you are dealing with research project uncertainty. Students who change their project constantly can – and sadly do – get positioned as ‘flakes’ by some supervisors. Given the nature of research project uncertainty, being called a flake is deeply unfair, but you can see how it’s easy to be painted this way if you turn up with a completely different project every time. One way to handle that absent supervisor problem is to get into the habit of a monthly status report. Write down everything that has happened in the project, at least once a month, and send it via email so you have a time stamped record. If your supervisor(s) don’t read and respond, at least you have a record you can produce later which explains the decisions you made.

I hope this quite long dive into research project uncertainty is helpful. It certainly helped me to write it. I might be screaming inside my heart, but at least I know what I am screaming about! I’ll do one more post before Christmas, in the meantime, solidarity with your own uncertainty.