Teaching connected-style handwriting, otherwise known as cursive handwriting, has fallen out of fashion on many school curricula. Older generations have sometimes been shocked that some younger people today can’t sign their names on official documents or even read a handwritten note.

Canadian provinces have seen a decline in teaching and learning cursive. In Ontario schools, for example, teachers might introduce cursive, but it’s not mandatory.

Such a development is reflective of larger trends of focusing less on teaching and assessing handwriting for itself — and more on what it’s communicating.

Alberta’s kindergarten to Grade 9 curriculum, for example, stipulates that students learn to “listen, speak, read and write” and also envisions outcomes that require printing, such as connecting prior ideas. But the curriculum doesn’t mandate assessing printing skills themselves. In Alberta’s 2018 new draft curriculum yet to be implemented, cursive is mentioned, but it’s not identified as a competency.

Beyond a nostalgia for the pre-digital age, there are good reasons why cursive handwriting needs to make a comeback. As a researcher who has studied the relationship of handwriting to literacy, along with other scholars, I’ve found that developing fluency in printing and handwriting so that it comes automatically matters for literacy outcomes. Handwriting is also an elegant testimony to the human capacity for written literacy and an inspiring symbol of the unique power of the human voice.

Too difficult?

In today’s age of digital literacy, many think handwriting is irrelevant altogether and a waste of precious instructional time. But touching a “d” on the keyboard, for example, does not create the internal model of a “d” that printing does. Keyboarding can wait.

Some may associate cursive with any number of outdated formats of handwriting that may have indeed seemed like a curse to master — loopy, twisty and hard on little hands in terms of muscle movement and also for visual memory.

But handwriting is only difficult if it is not automatic and, in turn, offloaded into long-term memory. Evolving research in the neurosciences underscores the importance of developing automatic skills in relation to what educational psychologists call the cognitive load.

Lessons learned from sports or the performing arts highlight the importance of establishing neuronal connections that promote fluid movement. With reading and writing, too, the keys to unlocking creativity or interpretation of story elements are also related to being able to write automatically.

Lack of fluency

By Grade 4, the cognitive demands of curriculum quickly accelerate: students must produce more, faster and better. Students who have fluent handwriting consequently have more working memory capacity available to plan, organize, revise and retrieve sophisticated vocabulary.

In a study I conducted with my colleagues of about 250 Grade 4 students in an Alberta school, we found that only about half of the students in our study achieved the necessary threshold in handwriting.

These children’s handwriting was insufficient to communicate the complexity of vocabulary and ideas expected in Grade 4. Most students had vocabulary they were not able to mobilize onto the page. Students’ failure to reach the required threshold of expression at this level is associated with a phenomenon recognized by researchers as the Grade 4 slump, a drop in outcomes from which students may not necessarily recover.

Improving literacy outcomes

Schools must and can do better, starting early. The key is not only teaching cursive, but a greater focus on all printing to cursive handwriting, spelling instruction and fine motor skills. These developments are essential for literacy foundations in the kindergarten to Grade 3 years.

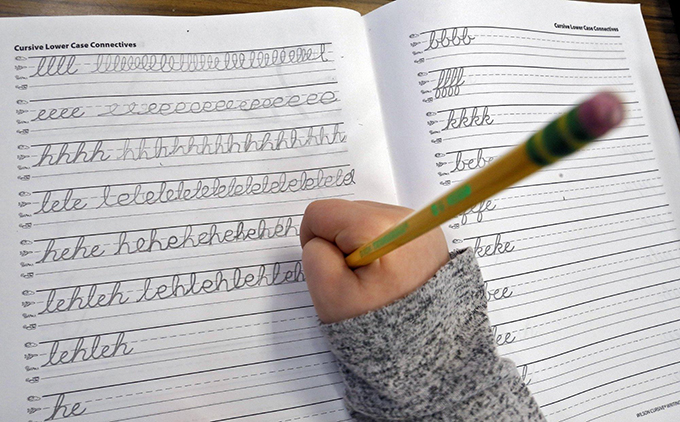

Building on these earlier skills, the key to improving academic outcomes in Grade 4 is teaching young students to connect their letters, resulting in a style of handwriting that is legible and fluent.

Steven Graham, an expert in special education, writing and literacy at Arizona State University, advocates for beginning with printing or “traditional manuscript”and transitioning to what he calls mixed mostly manuscript, whereby the child is learning a continuous stroke.

Similarly, an example from early literacy scholar Sibylle Hurschler Lichtsteiner of Germany shows a transition from manuscript letters to joined letters. It evolves naturally, with support, from children’s initial style of print in grades 2 to 3. Once young students have internalized stable, mental models of letter shapes, they can generalize and recognize various types of cursive script with a bit of practice.

Power of the pen

Testimonies draw attention to the power of cursive handwriting. The film Saving Private Ryan made famous the historical Bixby Letter written to the mother of sons killed in the American Civil War. While historians debate whether Abraham Lincoln or a member of his staff actually wrote the letter, ongoing interest in the letter through history suggests how human handwriting conveys personhood, care and captures imagination.

In our own era, Malala Yousafzai, the youngest Nobel Peace Prize laureate ever, reminds us:

“One child, one teacher, one book and one pen can change the world.”

Although Yousafzai first came to global attention via blogging, through her book Malala’s Magic Pencil she suggests a connection between the elegance and craft of a child’s handwriting and their personal agency.

Did you read #Malala's handwritten message about #Education First on #HandwritingDay? "I always dream…" #mHDay pic.twitter.com/u14W66CVBJ

— Malala Fund (@MalalaFund) January 23, 2014

Our society impoverishes children if we don’t learn from those who have gone before us. People who learn how to spell and to develop legible, fluent handwriting will have tools at their avail to confidently express themselves and circumvent inconveniences like losing power on one’s digital device.

It’s high time to put cursive skills back on the curriculum across Canada.

Author Bio: Hetty Roessingh is a Professor, Werklund School of Education at the University of Calgary