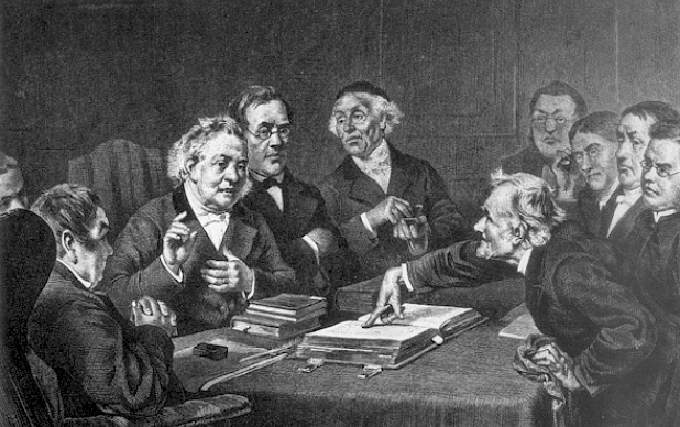

“Disputierende Theologen”

Holzstich von Bothe nach einem Gemälde von O. Günther, 1876

Religion and technology, at first glance, don’t go together. When I tell people that I research religion and robots, I’m often met with confusion. Interestingly, though, the religious figure of the golem, a mound of earth or clay that has been brought to “life”, is widely recognised as a precursor to the robot. And some of the earliest examples of moving mechanical figures (automata) were designed for religious purposes, as a form of worship and reverence for God’s creative work. So are religion and robots really that far removed?

One way of thinking about this is in terms of how secularisation – the idea that religion loses influence in society – has generally (although debatably) come to characterise Western culture. This has broadly polarised religion and technology. Religion is often seen to concern irrational, spiritual ideas and technology rational, scientific principles.

But there is growing concern that pioneers of new technologies – the likes of Apple, Google, and Facebook, who all reside in Silicon Valley – have paid too much attention to the technical.

The loss of the spiritual has been critiqued by, among others, French sociologist, philosopher of technology, and lay theologian Jacques Ellul, for whom “mystery is a necessity of human life”. As Ellul goes on to say:

Technique worships nothing, respects nothing. It has a single role: to strip off externals, to bring everything to light, and by rational use to transform everything into means.

For Ellul, as for philosopher Martin Heidegger, technologies are too shallow to facilitate mystery. He argues that they rob us of this essential part of humanness.

Technological humans

These fears are widespread, and include visions of human obsolescence, as well as of a loss of humaneness. Tech entrepreneur Elon Musk even thinks that designing technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) is like “summoning the demon”. Religious language is often used to express our relationship to technology, and it is usually employed as a form of critique.

Musk also talks positively about technologies, unsurprisingly, which we see in his enthusiastic proposals to build a human colony on Mars. Technologies that are within our control and that enrich our human depth, it seems, are to be encouraged. This is in line with religious ideas about the sanctity and value of the human made in God’s image. In that Musk talks about a way to use technologies to ensure the ongoing survival of our species, it is possible to find religious support for his ideas.

Explicitly religious attitudes and responses to technologies are also important to consider. For example, Skip Vaccarello, a technologist, has explored how some of his fellow technologists have found God in Silicon Valley. This is in response to the perception that, in Silicon Valley (and elsewhere), “business, technology, and money are worshipped as idols”: inadequate stand-ins for God.

At the heart of these religious ideas are reflections on depth and mystery. Significantly, these concerns don’t just extend to religious folk. When we ask about the possibility of loving machines, for example, we are touching on ideas about the depth of human love that may or may not exceed what can be programmed into machines. These sorts of concerns raise the question of how technologies suggest or compromise a sense of mystery and how we perceive it, which in turn affects how we interact with technologies.

Theologian Rudolf Otto refers to mystery when he describes how we as humans experience “the holy” as both “fascinans et tremendum” (awesomeness and awfulness). We seem to experience technologies in a similar way, with both promise and peril. Theological language, then, is an important resource for expressing – and understanding – how we think about technologies in terms of hope and doom.

Silicon Valley

Why, then, are we reluctant to connect theological reflection with technological development?

This ties in with a reluctance in Silicon Valley to address big themes and questions like what it is to be human and how a technological future might look beyond the realms of religion or sci-fi. Instead, there are calls for practical insights into how users will respond to and appropriate new technologies, so that we can determine their benefits and shortcomings, as part of their potential to change lifestyles and social patterns. Grandiose hopes and fears, it is claimed, obscure our awareness of and attendance to the more urgent everyday ethical challenges prompted by technologies.

Facebook, for example, has recently come under fire over its data privacy policy and its impact on the public sphere, global politics, and democracy. Likewise, other questions have now been raised more generally about how technologies are perpetuating or even exacerbating inequalities via algorithmic bias, as well as about the effects of automation on labour forces and lifestyle patterns.

These are, of course, crucial questions. But as philosopher of technology Evgeny Morozovnotes, the typical response is to develop new technological solutions. And as anyone who’s ever studied or even owned a piece of technology is well aware, no fixes are by any means permanent or perfect.

It’s not just the ethical problems that are important to think about, then, but also the dominance of a techno-centred “solutionist” attitude, according to which we develop technologies with a view to fixing our problems. What this attitude suggests is a faith in both human and technological abilities to determine and fix problems. In Silicon Valley, this is expressed most explicitly by how the main question is “can we do this?” rather than “should we do this?”.

Theology can respond to the second question. It can aid deeper reflection on what it is that we seek and value, and why. Theological discussions can help make sense of ideas about the mystery and sanctity of the human. Together with other philosophical explorations of technology, theology can contribute to the development of a reflective, rather than merely reactionary, ethics. In particular, it can help us to contemplate the myths we tell about ourselves and technologies as a way of evaluating the relationships between the two.

It’s not that Silicon Valley necessarily needs religious people. Rather, it’s that theologians are needed (as part of a wider crowd) to reflect on the tensions and relationship between the religious and the secular; to understand how this is important for how we think about rationality and spirituality; and thereby to cast additional light on what we value in a complex technological world.

=Author Bio:Scott Midson is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Lincoln Theological Institute, at the University of Manchester