I’m working on the second edition of ‘How to fix your academic writing trouble’ with Katherine Firth at the moment. We’re doing a new chapter on writing process, specifically how to think with generative AI tools. For inspiration, I am thinking about Artist Studios and how they support making work.

Artist studios are filled with tools and materials for creating, as well as storage for supplies and finished works. At the center of any decent artist’s studio is a workbench, where projects come to life. An artist’s studio is also a place of self expression: filled with inspiring objects to prompt the Artist’s creativity. Here’s what ChattieG’s DALLE3 thinks that looks like:

Not bad.

As a writer with a background in architecture, I no longer have a physical studio, but I still consider myself an artist of sorts, just with words. Over the past 20 years, I’ve generated a staggering amount of text files in my laptop hard drive. I have polished pieces – dissertations, books and articles – as well as half-finished drafts and abandoned ideas.

With each new computer, I’ve simply cloned the files from the previous one, avoiding the tedious task of cleaning up. As a result, my file mess has multiplied. Some of my best writing is all but lost, buried deep inside my digital freezer in a folder labelled ‘drafts May 2022’, or something similarly unhelpful. If I think about the inside of my laptop, it’s like a disorganised post office, with piles of unopened mail. I asked Chattie to make me a picture of this thought too:

Yeah, not bad Chattie. That’s how the interior of my computer feels. Maybe you can relate? Even if you are only at the start of your PhD, you are probably generating un-opened letters at a furious rate.

To be truly creative amidst this writerly mess, we need something to gently hold all that text, much like an artist’s studio supports the creation of art. Enter Obsidian. Obsidian is a database program, but that’s a bit like saying a library is merely a book storage facility. Obsidian is an elaborate knowledge management system for writers. It can hold thousands of bits and pieces of writing, both finished and unfinished, in a loosely organized way, allowing you to create with confidence, knowing that nothing is ever lost.

Obsidian works with markdown files (.md), which are essentially text files with some extra formatting. The Obsidian interface supports linking between these files, so individual pieces of writing become pages of your own personal Wikipedia. You can also access PDFs and images with Obsidian, enabling you to build a rich set of resources for your writing. A collection of these markdown notes, PDFs, and images is called an Obsidian Vault. A Vault stored locally on your hard drive can accessed by Obsidian and any other programs that can read markdown, like MS Word, making your notes more portable.

Obsidian is a different kind of writing environment built for the digital world, not to mimic analogue processes. If you think about it, MS Word is a digital form of a typewriter: producing digital letters, which sit in digital envelopes, stuffed inside digital pigeonholes. Because you can’t easily see inside all those files, you get the messy post office problem. By contrast, Obsidian is more like a terrarium – or one of those self contained eco-domes they lock people inside for five years to see if we could live on Mars. All your writing is viewable and searchable within a single interface.

I’ve written about Obsidian before as a way to keep notes for your PhD but I think I under sold the potential. It’s an incredibly powerful program, but so exquisitely customisable that teaching people how to use it is really hard. There is no single “right way” to set it up because every writer is different. Like an artist’s studio, the perfect Obsidian setup is a work of creation in its own right.

After talking about the teaching problem with my pod co-host Dr Jason Downs on the last episode of On The Reg, I decided to set up a sample Obsidian Vault. I created Coffee Vault by imagining myself as a researcher working on, well – the topic of coffee. It’s got a simple file structure and only two plug ins. Think of my Coffee Vault as a seed for your own Obsidian terrarium. Feel free to adapt it to your needs or start from scratch—we’re all different kinds of artists, and what works for me might not work for you.

You can download the Coffee Vault from my GitHub page, install it on your computer, and start exploring. It’s a good idea to look at the ReadMe file first, which has a set of instructions for the plug ins and some teaching notes. If you don’t want to download, you can simply go to this GitHub link, to see the file structure and look inside the individual notes to see how it works. My sample Vault holds a bunch of writing (composed with ChattieG and Claude Opus).

My Vault has a (kind of) logic developed after a lot of trial and error. I also watched countless videos of dudes talking about their Vaults on YouTube so you don’t have to (you’re welcome). The Coffee Vault has a logical structure inspired by Tiago Forte’s PARA system. It includes an Inbox for temporary storage, a Projects folder with subfolders for work in progresss, in this case a dissertation and book proposal. I have a Freezer for deep storage of valuable past writing, a Carpark for notes and thoughts, an Images folder for visual resources, and a Zotero folder for academic references.

While my sample vault is currently lightly populated in terms of content and links between documents, you can see the emerging structure using the “graph view” function:

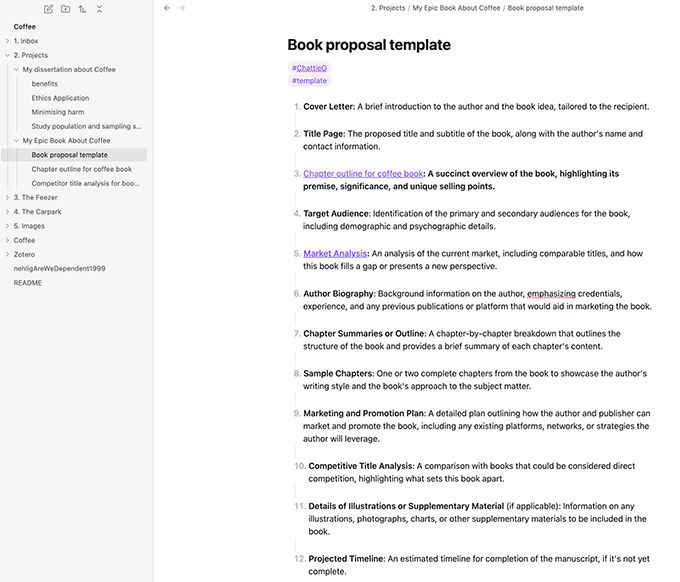

The Projects folder has two subfolders: one for a dissertation about Coffee and the other for a book proposal. If you go to the Book proposal note, you will see how I am working on pieces of the proposal as separate notes, with the book proposal outline as a kind of ‘contents’ page:

By distilling the task of the book proposal into separate notes linked to a ‘home page’, I can focus on one section at a time and avoid the temptation to ‘polish’ already finished text. In this way Obsidian allows you to write in ‘chunks, not chapters’, following advice offered by Pat Thomson and Barbara Kamler in their excellent book ‘Helping Doctoral students write’ (Pat continues to blog on Patter).

The Freezer folder is my imaginary ‘deep storage’ for text. Like most working researchers, I have a stock of past grant applications, briefing notes, reports, magazine articles and blog posts inside my messy digital post office laptop. I also have a bunch of references for people and old peer review reports. All these are relatively polished ‘genre pieces’ that hold extrodinary value as a personal store of training data for generative AI tools.

Recently, I wrote an article about Claude Opus for the AARE blog with only two prompts and a few edits. People were genuinely shocked by my mad skills of Claude, but it was possible to write this article in around 10 minutes because I already had plenty of finished examples of similar writing in my Vault. I simply showed Claude some of these samples, then wrote a list of the points I wanted to make in the article. Claude does me better than me – sometimes*. Many of us will write this way in the future, so you should think of all your finished writing as your own store of training data. Obsidian can help you keep this valuable past IP tidy and accessible.

The Carpark is the place I put what I typically think of as ‘notes’ – tentative thoughts finding their way into writing but not yet fit for public consumption. The Carpark is really my attempt to build a Zettelkasten: a note taking method documented in Sonke Ahren’s How to Take Smart Notes. There’s a lot of buzz about the Zettelkasten idea, with a lot of dudes on YouTube making big claims that working this way will change your life… In my experience the Zettelkasten doesn’t work quite as advertised, but every writer needs a place to store thoughts and Obsidian’s ability to make links between these thoughts is useful.

I have a separate folder for Images, mostly so I can easily locate them when it comes time to publish something. Finally I have a Zotero folder. The Zotero Integration plug in enables me to highlight text and make notes on PDFs inside Zotero and sync them into Obsidian. The plug in relies on a template file to format the notes and highlights into markdown. It took me a long time to get this bit of my Vault functional, so I’ve supplied my Zotero integration template based on an example supplied by Peter Hayes (thanks Peter!). I’ve included some notes on how to set it up in the ReadMe file.

Setting up an Obsidian Vault may seem complicated – that’s because it is. If you’re new to the program, you might want to start by simply installing Obsidian (it’s free) and experimenting with its features before diving into my Coffee Vault. At the very least I hope I have inspired you to explore Obsidian’s potential. Stay tuned for the second edition of ‘How to fix your academic Writing Trouble’ – we hope to have it out in the new year.

*I wrote the first version of this post and put it into Claude Opus to see it if could be improved. Claude did an ok job, but seemed to struggle with the step by step detail and the quirks of my writer’s voice, which is weird because other times it’s done a bang up job. Maybe it thinks it’s the spring break? Anyway, I used some of what it gave me, but this one is mostly what Mr Thesiswhisperer calls IngerGPT