When summer approaches, many college students (and their parents) wonder how they can land the perfect internship. But what kind of résumé really impresses firms looking for interns? And how are the internships connected to the broader job market?

We are researchers who specialize in issues of labor economics and employment, particularly for interns and recent college graduates.

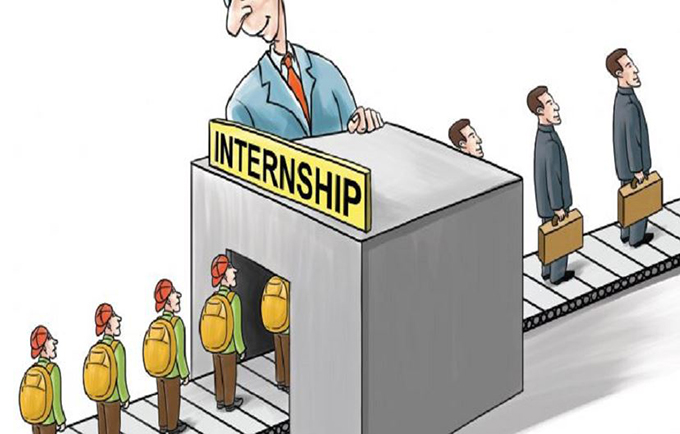

In a recent study we did on the demand for interns, we found that employers were more likely to contact applicants who had a prior internship. In other words, it often takes an internship to get an internship.

We also found that there is a close relationship between the market for interns and the local unemployment rate. Labor markets with higher unemployment rates are less likely to have paid internships. And applicants are less likely to be contacted when the unemployment rate is higher. As other research has shown, we found that applicants with white-sounding names got a higher response than those with black-sounding names.

Apply often

To shine light on what employers look for in a prospective internship, we sent about 11,000 fictitious résumés to firms to see how they would respond. The résumés contained information about the candidates’ GPA, major and previous work experience. These fictitious applicants presented themselves as students at one of 24 large public universities. They were also assigned distinctively black- and white-sounding names.

We applied for internships in all regions of the U.S. in the fields of marketing, research and business, which represent the majority of internships that were advertised. We applied both to paid and unpaid internships and recorded a “positive response” when firms requested further information or actually offered an interview.

Overall, we received a positive response from firms about 6% of the time. That’s about one response for every 17 applications. So one lesson is that students need to send out many applications for internships to land one eventually.

Perhaps not surprisingly, we found that firms offering unpaid internships were about twice as likely to contact our applicants. The rate for paid internships was about 3% versus a little over 8% for unpaid internships was. It appears that firms need to work twice as hard to find unpaid interns as they do paid interns.

Grades, schools and names matter

We found that applicants with better grades were more likely to hear back. The positive response rate was statistically significant – about 1 percentage point higher for applicants with a GPA of 3.8 or 4.0, versus 3.0 or 3.2.

We also found that students from more selective universities were more likely to receive a positive response.

As with prior studies, we found that applications with black-sounding names were less likely than those with white-sounding names to elicit interest, all other things being equal. In our study, black-sounding names got a 30% lower response rate, even after taking things such as GPA into account.

Proximity and prior experience

We found that the probability of a positive response fell by eight-tenths of 1 percentage point for every time you double the distance of the internship from where the applicant lives. Students’ chances of landing an internship are greater closer to their university or home.

One of the results we found to be the most striking is that applicants with previous internships were about 25% more likely to be contacted about their application than applicants with other types of previous work experience – including jobs in restaurants, retail, campus sports, or volunteer work.

We found that this effect was particularly notable for part-time internships.

Internships play a big role in how well people do later on in their careers. If firms are more likely to respond to applicants for unpaid internships – and having prior internship experience substantially increases a student’s chances for getting subsequent internships – then the inability to take an unpaid internship because of financial reasons could hurt your chances of finding a job in the future.

Labor market impact

We also found a strong link between the regular labor market and whether employers respond to applications for internships. Every time unemployment goes up by 1 percentage point, the response rate for internship applications went down by nearly 5 percentage points. This effect is about 10 percentage points for unpaid internships but close to zero for paid internships.

In our data, just over 60 percent of internships are unpaid, but this percentage varies geographically. One of the most important things that determine whether an internship is paid is the unemployment rate in the local labor market. We found that places with lower unemployment rates are more likely to have a greater share of paid internships, possibly because firms are trying to entice applicants with an eye towards hiring them more permanently.

Labor markets with higher minimum wages are less likely to have paid internships, we found in our study. For every US$1 increase in the minimum wage in a local labor market, the share of paid internships decreases by 4.6 percentage points. With higher minimum wages, paid internships cost firms more, so firms may prefer to switch to unpaid interns.

Taken together, our results suggest that students who live in areas with higher unemployment rates, or in areas with higher minimum wages, may face more difficulty in landing paid internships. The same is true for students who have no prior internship experience. Since internships are important to finding a job in the future, such students may be at a long-term disadvantage.

Leveling the playing field

How can these disparities be addressed? Paying interns, as some politicians have suggested, could help. So could making internships part of the high school and college experience.

If unpaid internships are eliminated, it could deprive students who take unpaid internships of valuable learning experiences. Need-based scholarships – funded by government, colleges or philanthropy – could enable students to take internships that would otherwise be unpaid.

Author Bios: David A. Jaeger is Professor of Economics at the University of St Andrews, Alan Seals is Associate Professor of Economics at Auburn University and John M. Nunley is Professor of Economics st the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse