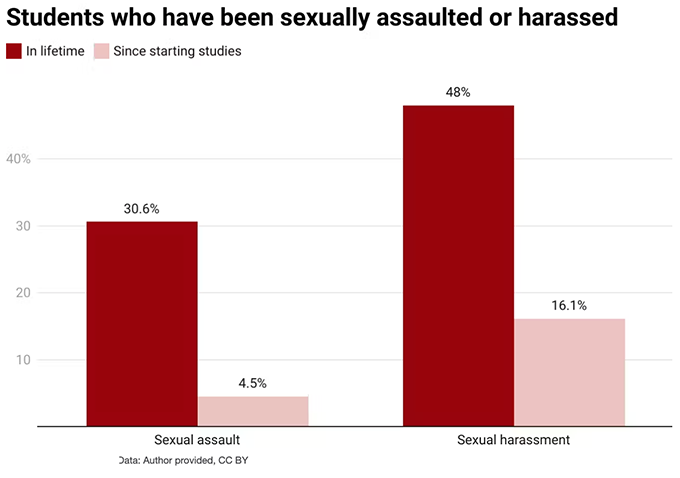

One in three university students (30.6%) have experienced sexual assault at least once in their lifetime. This is one finding from the 2021 National Student Safety Survey (NSSS) report, released today.

The survey responses from 43,819 students enrolled in 38 Australian universities, as well as written responses from 1,835 current and former students, demonstrate the extent and impacts of sexual violence in and beyond the higher education sector.

The survey also found one in 20 (4.5%) had been sexually assaulted in a university context since starting their studies. In the 12 months preceding the survey, 1.4% of women and 0.6% of men reported experiencing sexual assault in a university context.

Rates of sexual harassment were much higher. One in two students (48.0%) had experienced it at least once. One in six (16.1%) had been sexually harassed in a university context since starting their studies, and one in 12 (8.1%) in the preceding 12 months.

Sexual violence reflects patterns of inequality

Universities Australia funded the survey under the Respect Now Always initiative. It builds on a legacy of previous work, including the Australian Human Rights Commission’s 2016 national survey of university students on sexual assault and sexual harassment. That led to its 2017 report, Change the Course.

Five years on from the Change the Course report, students are still demanding more effective action. David Moir/AAP

The 2021 survey also explored student attitudes and knowledge about sexual violence and reporting processes, establishing a benchmark against which universities can measure their progress into the future.

The past two years however have been a time of COVID lockdowns – and it’s likely this impacted on the 12 month results of sexual harassment and assault in university contexts. Only a third of students (33.6%) in the 2021 survey said they had been able to take part in some or all of their classes on campus. It is also worth noting improvements to the survey methodology mean the 2021 prevalence results are not directly comparable with the 2016 results.

Nonetheless the 2021 data still suggest about two students in a tutorial class of 25 would have been sexually harassed or assaulted in a university context at least once in the preceding 12 months.

That is no small problem.

And it is not an evenly spread problem either. Much like the 2016 survey, rates were highest for students who were women, non-binary gender or transgender, sexuality diverse, disclosed a disability or were younger (18 to 21 years).

It happens on and off campus, and is rarely reported

For sexual violence on campus, we can expect universities to be responsible for ensuring a just and timely response, and to take action to prevent these harms. Many of the instances of sexual harassment and sexual assault that impacted people most, as reported in the 2021 survey, did happen in settings such as lectures and classes, libraries, clubs and events, and student accommodation.

But, of course, not all such experiences were on campus. As is the case in society more generally, sexual assault in particular often happened in private homes or residences.

Whether on or off campus, though, a majority of perpetrators were known to the victim through their university. This has significant implications for victim-survivors’ safety and well-being in their ongoing studies.

It is also telling that one in two students who responded to the survey said they knew little or nothing about their university’s reporting or complaint processes.

Overall, few students, about one in 20, formally reported the experience that impacted them most to their university. Many thought it would be too hard to prove, or that they wouldn’t be taken seriously.

Universities have a particular duty to act

Sexual violence is a human rights issue, and one Australia has committed to addressing through our national policy plans and prevention frameworks.

Our universities have a crucial role to play in responding to sexual violence. Whether it happens on campus or elsewhere, universities can help ensure victim-survivors are supported to feel safe in continuing their studies – rather than bearing the impacts of sexual violence alone.

Yet universities also have a role in preventing sexual violence through addressing the inequality and discrimination that fosters these harms.

Some efforts, such as the Educating for Equality initiative, have begun to be implemented. But clearly, more needs to be done.

Students have a vision for change

University students themselves have a clear vision of the role of universities to address and prevent sexual violence.

Through the 2021 research they called for more transparent reporting processes, as well as awareness campaigns so students know what sexual violence is and how to report it or seek help. They wanted visible and proportionate disciplinary action for perpetrators to show universities take such reports seriously. And they wanted properly resourced supports for victim-survivors.

Beyond this, students called for universities to work collaboratively with victim-survivor advocates, and take a more active role in promoting equality and respect on their campuses and beyond.

The 2021 NSSS research tells us sexual violence remains a problem and students are demanding action.

What remains is for universities to demonstrate they are fully implementing and funding the necessary actions – and in doing so, to ensure no institution is left behind.

Author Bio: Anastasia Powell is Associate Professor, Criminology and Justice Studies at RMIT University

The author acknowledges the contributions of the Social Research Centre as the lead organisation on the 2021 NSSS reports. In particular, acknowledgement is made to Dr Paul Myers and Dr Wendy Heywood.