In the past five years, higher education has been in a seemingly endless state of disruption.

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a mass rapid pivot to emergency remote teaching. In shifting to unfamiliar digital learning environments, instructors scrambled to replicate classroom learning online. When restrictions lifted, many institutions pushed for a “return to normal,” as though the pre-pandemic educational standard was ideal.

Now, with generative AI disruptions, we are seeing a similar desire to cling to an idealized vision of the modern university. AI has unsettled long-established forms of assessment, simultaneously instigating a return to older assessment models in the interest of “academic integrity.”

If students navigating higher education believe the goal is to pass rather than to learn, then student misuse of generative AI technologies is nothing more than a rational action by a rational agent.

For meaningful university education, we need to shift to a process of building relations and knowledge with others through dialogue and critical inquiry. Part of this means taking lessons from pre-industrial forms of learning and contemporary educational movements.

We also need to shift from compliance-based assessments and grading to meaningful and supportive feedback and opportunities for growth, rooted in teaching and learning with care.

‘Knowledge factory’ invites generative AI misuse

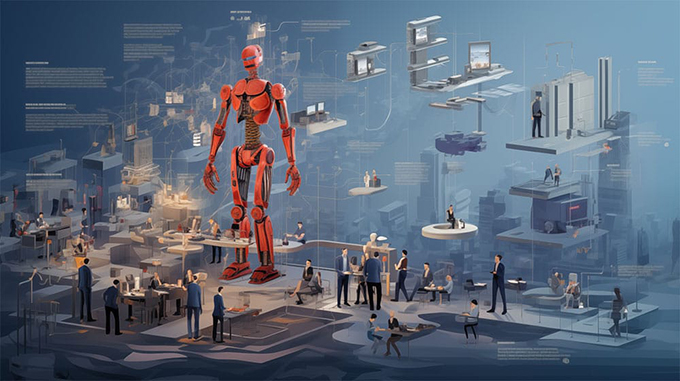

Modern higher education systems in North America often function as a “production enterprise” or a “knowledge factory” focused on research outputs and producing skilled graduates.

Philosopher Jean-François Lyotard described how contemporary education is designed to manufacture educated individuals whose primary role is to contribute to the optimal functioning of society — a class of people he refers to as “intelligentsia.”

He argued that education produces two categories of intelligentsia: “professional intelligentsia” capable of fulfilling pre-existing social roles, and “technical intelligentsia” capable of learning new techniques and technologies to contribute to social progress and advancement.

These roles align with some actions being taken in higher education institutions to respond to generative AI interruptions. For example, institutions are:

- Taking steps to ensure that graduates are authentically skilled and credible in order to fulfil existing professional roles despite generative AI influence or;

- Enabling students to develop “AI literacy” in order to remain competitive in the workforce and contribute to social progress.

If we concede that the primary purpose of higher education is to feed the workforce and enable social and economic progress — a “knowledge factory” or “production enterprise” — then ensuring graduates are authentically skilled at AI or enabling them to develop AI literacy can be seen as rational responses to generative AI disruption.

Misalignment with meaningful learning

Mirroring the observations of Lyotard, cultural critic Henry Giroux argues that when shaped by market-driven forces, the purpose of higher education shifts from democratic learning and critical citizenship to producing “robots, technocrats and compliant workers.”

This infusion of corporate culture in higher education has created the conditions that make it particularly vulnerable to generative AI.

Some key characteristics of the knowledge factory model of education include standardized tests and assignments, large class sizes, an emphasis on productivity over process and the use of grades to indicate performance. Many of these existing practices are outdated and often misaligned with meaningful learning.

For example, traditional exams shift learners’ focus from learning to performing, often amplifying existing inequities. Debates around the efficacy of lectures have been raging for years.

Grading practices are inconsistent and have a detrimental effect on learners’ desire to learn and willingness to take risks. When students feel a lack of autonomy, they tend towards avoiding failing rather than learning. This is another compelling reason for students to adopt technologies that remove any friction or discomfort caused by learning.

Importantly, these conditions pre-date the arrival of generative AI. Generative AI simply highlights how instrumental logic — the factory model of university — can hinder learning.

Alternative ways to imagine education

In a time of information abundance and overlapping crises of deepening social divides, climate breakdown and rising authoritarianism, those with the agency to shape higher education (including educators, policymakers, staff and students) can draw on alternative visions of higher education to create meaningful places of learning.

Pre-industrial education served markedly different purposes than the current model of education, creating environments that would likely have been much more resistant to generative AI disruption.

In the ancient world, Plato’s Academy was a place of educational inquiry fostered through discussion, a multiplicity of perspectives and a focus on student well-being.

Access to the academy was exclusive, with the majority of students being wealthy enough to cover their own expenses — and only two documented female students. However, in spite of this elitism, the absence of standardized curricula, exams and formal grading allowed learning to be built on relationships and dialogue.

Contemporary educational movements

Higher education can, and historically has, offered more than a pathway to economic advancement. Multiple emerging ways of teaching and engaging learners also offer alternative visions of higher education that recentre learning and the learner.

The ungrading movement refocuses education on learning by emphasizing meaningful feedback and curiosity and moving away from compliance-motivated grading practices.

The open education movement resists the transactional nature of industrial education. It empowers learners to become producers of knowledge and reimagines the boundaries of education to expand beyond the classroom walls.

Other modern educational movements, commonly associated with the work of philosopher Nel Noddings in the 1980s, place an ethic of care at the centre of teaching and learning. Teaching with care focuses on creating learning climates that holistically support learners and educators. It also recognizes and embraces diversity, and acknowledges the need to repair educational systems.

Each of these approaches offer alternative visions of higher education, which may be less susceptible to AI automation — and more aligned with higher education as places of democratic learning and connection.

The university of the future

The knowledge factory model is outdated and ill-suited to meaningful learning. In this form of education, generative AI technologies will increasingly outperform students.

Reimagining higher education today is neither nostalgic nor Utopian. The students of today come to post-secondary institutions needing, above all, hope; we owe it to them to help them find meaningful purpose while learning to navigate an increasingly complex world.

Author Bios: Dani Dilkes is a PhD student, Digital Learning, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto and Mark Daley is Professor of Cpmputer Science & Chief AI Officer at Western University