Most research development models assume that time, energy, and executive functioning are equally distributed across scholars. They aren’t. Especially not for early career researchers in teaching-heavy roles, and certainly not for neurodivergent academics trying to survive in systems not designed for their minds.

We need a better way to support scholarly growth—one that respects rhythm, autonomy, and constraint without sacrificing rigor. This is the proposition I want to make: that we can design structured, high-quality research programs outside traditional PhD and postdoc models. Programs grounded in trust, cognitive justice, and realistic timelines. Programs that don’t ask scholars to contort themselves into forms of productivity that were never meant for them.

I call this the Self-Directed Research Model—a publication-driven, mentor-supported research pathway that I’ve recently developed. I am now sharing it publicly, with the hope that others will find it useful and perhaps join me in refining and implementing it.

What’s Broken in Traditional Research Pathways?

The problems are widely known, even if unequally experienced:

- Early career scholars often juggle multiple teaching loads, administrative duties, and family responsibilities, leaving little time for sustained writing or publication planning.

- Neurodivergent scholars—those with ADHD, autism, dyslexia, or sensory processing differences—often struggle with institutional expectations around linear productivity, strict timelines, or narrow definitions of organization and rigor.

- Global South academics face funding precarity, uneven mentorship access, and systemic barriers to publishing in international journals.

Put simply: most academic development pipelines assume ideal conditions. But the people most in need of support often inhabit the least ideal ones.

That includes me.

After completing my PhD in Aotearoa New Zealand, I returned to the Philippines deeply motivated to publish and extend my research. But I also faced immediate limitations: a full teaching load, a lack of postdoctoral options, and the ongoing challenges of managing ADHD in a bureaucracy-heavy system. I didn’t lack drive. I lacked structure that matched my way of thinking.

So I designed one.

The Self-Directed Research Model (SDRM): A Trust-Based Alternative

The Self-Directed Research Model is a two-year, publication-driven framework designed for scholars who want to produce sustained, high-quality research without the formal structure of a postdoc or PhD. It provides:

- A trimester-based schedule: six four-month terms, each dedicated to a key research theme or question.

- Article-to-book integration: each term’s output is a journal article that builds toward a cohesive book or report.

- Flexible pacing with soft accountability: you set the goals, rhythms, and outcomes—but do so with structure and support.

- Informal mentorship: ideally through a “body-double” supervisor who provides monthly check-ins, feedback on drafts, and reading curation.

While I have yet to pilot the model formally, I am sharing it now in the hope that others—especially fellow early career and neurodivergent scholars—might see in it a path forward.

What Makes This Model Different?

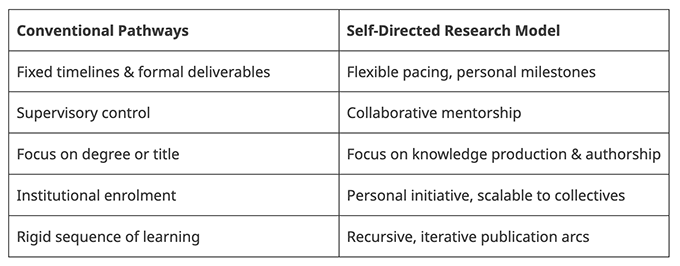

The Self-Directed Research Model is not just about working independently. It’s about rethinking the assumptions that underpin most academic development tracks.

The model assumes that rigor and flexibility can coexist, and that research development is not a one-size-fits-all process. It invites scholars to take ownership of their own arc—not in isolation, but in trusted conversation with mentors and peers.

A Quiet Endorsement: Inger Mewburn’s Response

Before sharing this model publicly, I reached out to two scholars working in researcher development. One of them—Prof. Inger Mewburn, widely known as The Thesis Whisperer—responded with generosity and insight. She described the model as “excellent scaffolding” and praised its clarity, particularly its attention to the needs of neurodivergent researchers and teaching-heavy academics.

She also valued the model’s thoughtful structure—its clear deliverables, publication arc, and transparency around expectations and co-authorship. Though she was unable to take on the role of informal mentor due to her existing responsibilities, she affirmed its promise, writing: “This kind of structured yet flexible approach to researcher development addresses real gaps in our academic systems.”

I share her words not as endorsement, but as encouragement. This model, still in its early form, feels worth trying.

What This Model Makes Possible

This isn’t just a model for individuals. It can be scaled, adapted, and institutionalized:

- Universities could offer Self-Directed Research Model-style fellowships for part-time faculty or staff building their research portfolio.

- Research centers could provide mentorship matching and small publication grants to scholars pursuing this track.

- Academic networks could convene Self-Directed Research Model cohorts—peer-driven research groups operating across countries or disciplines.

For Global South institutions, this model offers a way to build intellectual capital without massive funding investments. For institutions in the UK, Australia, North America and beyond, it provides a framework for supporting underrepresented scholars without defaulting to bureaucratic constraints.

Most of all, it shows that we don’t have to choose between structure and inclusion. With thoughtful design, we can make room for both.

An Open Invitation

This model is still an experiment—but one I hope others will help bring to life. If you are a scholar seeking rhythm, a mentor open to new roles, or part of an institution curious to try alternatives, I’d love to hear from you.

There are many of us cooking outside the PhD—improvising, experimenting, holding things together with borrowed tools and slow hope. Maybe it’s time we made a table for it.

AI Acknowledgment

Portions of this blog post were drafted and refined with the assistance of ChatGPT, used as a thinking and writing partner to structure arguments, test language, and reflect on emerging ideas. All content reflects the author’s lived experience, conceptual contributions, and editorial judgment.

Author Bio: Dr. Karl Patrick R. Mendoza is Associate Professor at the Department of Communication Research, Polytechnic University of the Philippines. He writes on trust cultures, research pedagogy, and neurodivergent inclusion in academia.