The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, awarded notably to Philippe Aghion, has brought renewed emphasis to the benefits of technological innovation and its crucial role in economic growth. But are there not also forced innovations? The philosophy of Ivan Illich can shed light on this question.

In theory, we are all free to buy or not buy new smartphone models, or to adopt new technological generations. In practice, however, it is very difficult to resist. Research on customer resistance to innovation is increasing. Some studies address the issue of forced innovation, primarily within companies and government agencies . The very structure of markets can lead to these situations of forced innovation .

A number of dominant market players can impose products that are more profitable or advantageous to them. A prime example is Enedis’s Linky “smart” meter. Despite resistance from individuals and even sometimes local authorities, very well analyzed in the work of Cécile Chamaret, Véronique Steyer, and Julie Mayer , the installation of this meter has become mandatory.

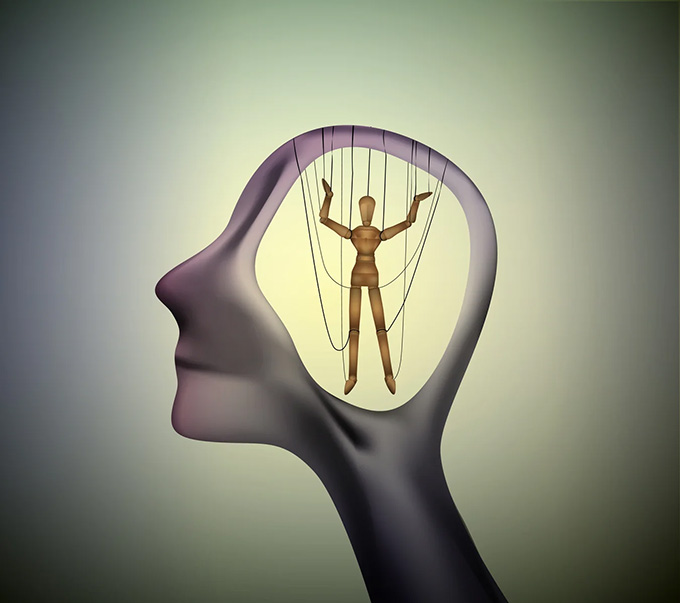

So, do we have free will to decide whether or not to adopt a new technology?

Control of free will

In his book *Conviviality* (1973) , the philosopher Ivan Illich explored the concept of the creation of needs through what he termed “radical monopolies.” According to this critical thinker of industrial society, institutions exert control over individual free will by creating needs and solutions out of thin air, thereby fostering dependencies. These radical monopolies can be found in medicine, transportation systems, and education.

This situation is particularly problematic because it fosters widespread dependence among individuals on these “radical monopolies” that control the satisfaction of needs. The pursuit of profit in industrial production takes precedence over genuinely meeting the needs of the population. Ultimately, this leads to an alienating consumer society where individuals lack both autonomy and the capacity to make informed choices.

The individual caught in the shackles of innovation

For Ivan Illich, innovation plays a key role because it is the response to these created needs; the individual finds themselves trapped in its chains. This counterproductivity of innovation manifests itself in the deterioration it causes to human beings themselves, to their autonomy and their capacity for consciousness. It also affects their environment, because institutions “create needs faster than they can satisfy them, and while they strive in vain to do so, it is the earth they consume.”

The lack of reflection on the true necessity of innovation, and the absence of any prior evaluation of its value, ultimately have consequences for our resources. Each new smartphone, computer, social network, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence brings no less counterproductivity than what these innovations are supposed to deliver: freedom, openness and connection to others, independence, etc.

Doesn’t the race in which innovation is engaged, at an ever-increasing speed, gradually lead humanity not to progress, but to its downfall?

Having or using the latest trend

In recent months, two high-profile innovations have launched: OpenAI’s ChatGPT 5 and Apple’s iPhone 17. The former, a new version of OpenAI’s generative AI, promises improved logic, expanded multimodality (text, image, video), and increased speed compared to its predecessor. The new version of Apple’s most famous smartphone, meanwhile, features a slightly brighter screen, a dual rear camera optimized for low-light conditions, and the ability to record simultaneously with the front and rear cameras.

For the vast majority of uses, in either case, no real difference is perceptible to users. The proposals are more about symbolic benefits (having or using the latest technology) than benefits related to actual use. The European Responsible Innovation Barometer shows that only 59% of the population in France believes that science and technology “make [their] lives easier, more comfortable, and healthier.”

In contrast, manufacturing a smartphone requires the extraction of around fifty different metals, and the production of new devices accounts for 60% of the environmental impact of digital technology in France, a sector that is itself experiencing strong growth . As for Chat GPT5 , according to a recent study by the University of Rhode Island, it uses an average of 18 watt-hours per response provided, equivalent to an incandescent light bulb operating for eighteen minutes.

Little added functional value

These two recent examples are in no way inferior to other equivalent developments.

Netflix’s 4K image quality requires upgraded capture (cameras) and display (computer or television) equipment, as well as a more expensive Premium subscription, despite the minimal difference visible to the naked eye. The Wi-Fi 7 protocol offers higher speeds, reducing download times from around thirty seconds to ten seconds for a high-definition film, but necessitates replacing all equipment (router, terminals) .

It may seem surprising that these innovations are successful despite the limited functional added value they provide. But can we, as consumers, resist this technological onslaught?

Constant update

In the digital realm, the operation of networked products necessitates a system of continuous updates. This effectively renders older hardware models or older software versions unusable . To run the latest email versions, for example, it’s necessary to download a sufficiently recent operating system, which itself requires memory available only in newer smartphone models.

The option to keep an older version is not available, even if one is not interested in its new, often highly specialized, features. Individuals are forced to keep up with technological advancements, even remotely. Without having wanted or intended to do so, they find themselves drawn into new practices, which can then be perceived as genuine needs.

Pro-innovation bias

Developing a global economy of innovation has become key. If individuals cannot resist innovation, can societies do so at a global level? As management professor Franck Aggeri points out , Schumpeterian theory suffers from a pro-innovation bias, often downplaying or ignoring the negative impacts of innovations.

The concept of extended value , which adds value – positive or negative – for the planet or for society to the value for the consumer, allows us to extend the reflection, but is not operated at the macroeconomic level.

The overall economics of technological innovations are never considered, no innovation is presented from a global, complex perspective, with losses, profits, and collateral damage.

Author Bios: Xavier Pavie is a Philosopher, Professor at ESSEC, Program Director at the International College of Philosophy and Emmanuelle Le Nagard is Professor of Marketing both at ESSEC