Over time all researchers build a knowledge base about their key interests. A large part of this knowledge is a core set of literatures. They/we do need to keep up to date, but they/we can rely on – and use – our incrementally expanding personal library of literatures. However, every so often, researchers have to deal with a completely new topic and brand new literatures.

My colleague Lexi Earl and I are currently writing a book about school gardens. Learning gardens are pretty popular at the moment. They are promoted by celebrity chefs and by environmental scientists alike – and many schools believe gardens are a great place to learn about the processes and practices of cultivation and/or to appreciate the natural world.

Lexi and I have done some research, school garden case studies, and we now have plenty to say. But we thought that we needed to start our book, contracted to Routledge, with some historical discussion about school gardens, because now is not the only time when they have been popular. We had a hunch that there might well be something to learn from what had happened before.

So this meant that we had to find a load of new books and new articles – well, I mean new to us. And that meant …. reading. And lots of it.

We were pretty keen to find primary source material as well as literatures from contemporary educational historians. And so there’s been a fair bit of archival searching as well as the journal and book based searches we are used to doing.

We are immensely grateful to the generations of librarians who have catalogued, conserved, digitised and weblogged the books and reports that we are using. The British historian Raphael Samuel often argued that doing history was a collective endeavour – the introductory thanks to the army of librarians that make writing histories possible are just too little recognition. That’s certainly our experience too.

We have had to come to terms with this historical material fairly quickly. But this history chapter is mine to draft first of all so I have done most of the primary source reading. Lexi is focussed on other reading about current school garden issues and so she is adding additional points into my draft.

But i haven’t just done any old kind of reading. I have been reading with a purpose – we already knew the key areas we were interested in from our case studies. Because we are taking a genealogical approach (Foucault), we are interested primarily in how gardening in schools is and has been understood and categorised. as well as practiced.

I approached the historical texts with five key questions:

- What’s the purpose of a school garden? What’s the problem for which school gardening is the answer?

- What is the garden – what is important about it (size, plants location etc)

- What school subjects is the garden connected with? What is the disciplinary basis of teaching?

- How is the garden organised?

- What successes and problems are encountered in establishing and sustaining the garden?

I then recorded details of each text in bibliographic software.

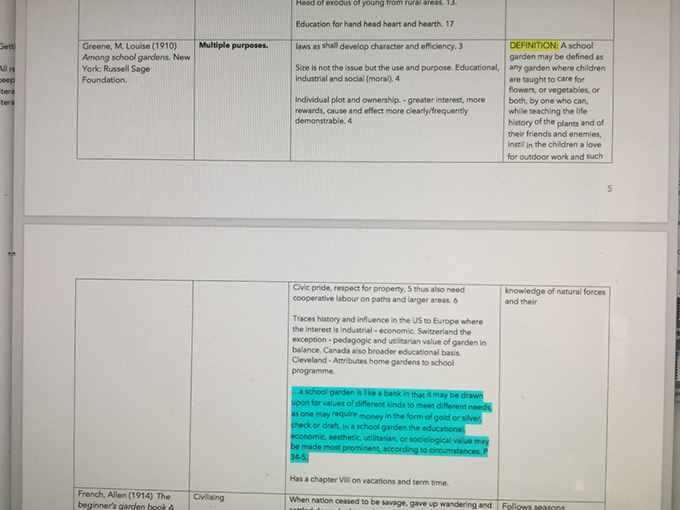

Then I wrote the answers to our questions into a landscape table. Below, an example of the record of one key book – designated key because we saw that other historical texts referred to it, and it was also referred to a lot in contemporary accounts. You can see here that I’ve bolded the major point that this book talks to, and I’ve highlighted bits I think I might use in the draft chapter

After I’d read all of the texts and recorded details on the table, I then wrote some very short notes on the answers to our questions. These were more in the form of a synthesising memo than an outline.

I then

- decided on the argument for the chapter, (a Tiny Text), you might use mind mapping to get to the argument

- decided on a structure – I divided the material into three big sections (in this case, philosophy, historical accounts, contemporary accounts) and then I

- wrote an outline.

Finally I started to generate text. A first draft. This drafting process did involve shifting some things around in my initial outline. But mainly I had to keep going back to the table to ensure that I brought all of the material about any single point together. I also frequently went back to the digital books.

So the drafting was actually working with at least three and sometimes four documents on the desktop – table, memo and original text as well as the developing first draft. If you are a Scrivener user then this all happens within the software. I’m not, largely because I like to insert the references as I go, so my Endnote is always open too.

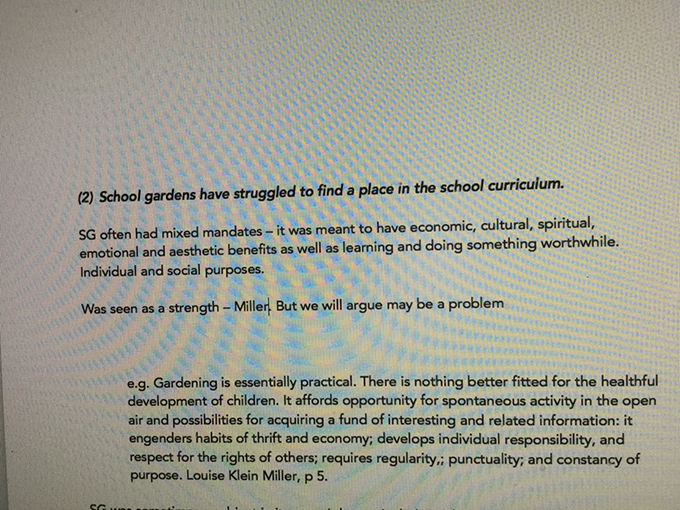

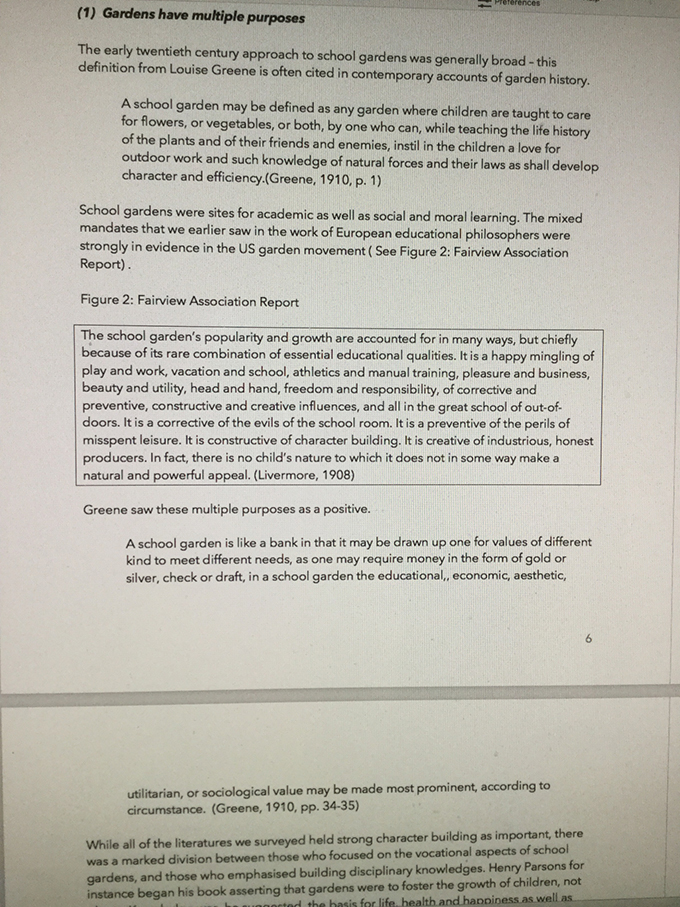

You can see what a small section of this first draft looks like.

You will see that I have presented some historical “evidence” which I will then read critically to see: what is presented and how, what is put together, what assumptions are made, where there are tensions or differences, what is missing, what the consequences of thinking in this way might be and why this might matter.

And of course this first draft might be completely changed as I start to revise. Who knows how much the final version will look like this? ????

But please don’t think this is how you must work.

A concluding caveat. I am often asked how I work with literatures and will I show and tell. So I’ve done some. But I do try not to do a lot of display of my own processes, as my methods are bespoke to me.

And a confession. I’ve been doing this a long time. In this kind of overview work, I tend towards pretty minimalist noting – I actually spend much more time thinking about the questions I want to ask of a text than writing notes. When I am teaching people how to work with literatures I generally use more notes and write more memos. When I do my own work, I’m a bit lazy, I rely on my short term memory probably too much, and I tend to shortcut some written processing.

And most important – this is not the only way to do literatures work. I am pretty sure that Lexi does this differently – I have seen her taking a print-it-out-and-highlight, notes-on-the-printout-and-then-themes- in-a-memo approach. That works just as well.

No matter the techniques used, both our approaches will mean that our final text is firmly connected with the literatures through our critical reading – and our work will read seamlessly as if we are one person writing!!!

But that’s another post.