Among the civilians of countries attacked militarily or victims of persecution, child figures – child victims, children displaced as today in Ukraine, refugees, or even child soldiers – have fueled for several decades the renewal of scientific research on the warlike violence.

The research first focused on the child as an object of mobilization of war discourse, national and international social policies, and humanitarian aid. Taking part themselves in the mobilization around the victims, the media images of children arouse the emotion, to very variable degrees, according to the degree of proximity of a conflict.

In A Century of Refugees , Bruno Cabanes also underlines the “constant ambiguity between the photography that documents exile, the one that delights in the spectacle of suffering and the one that fuels, sometimes voluntarily, the fear of the migratory invasion” . These representations are profoundly revealing of adult points of view, of collective sensitivities, and sometimes of propaganda.

Alongside studies on the mobilization and care of the child, based on the discourses and practices of the viewer , more recent works focus on children’s experiences of war, studied through the traces they left behind: diaries, letters, drawings… These childish sources reveal the child’s own view of war and exile: they allow us to get closer to the experience, the lived dimension of the event.

Thus, the child whose words or drawings are collected is part of the history of wars, and his graphic testimony is precious, not only for measuring the psychic impact of a conflict on the child – according to the approach of the sciences of the psyche – but also, in other disciplines of the human and social sciences, to assess the specific qualifications of certain conflict situations involving civilians in particular: war of aggression, occupations, bombings, mass destruction, so-called crimes of “profanation” , attacks on filiation, crimes against humanity…

Humanitarian issues are paramount; but these representations also make it possible to write the story of a determined conflict “at the height of a child” , and to place it in a story of childhood in war and in exile.

Pioneering work

The reading of children’s drawings is fueled by pioneering commitments, in particular at the time of the Spanish Civil War, with the activity of Alfred and Françoise Brauner, which has been the subject of the scientific work Childhood, Violence, Exile (EVE). In the perspective of a history of childhood “at the height of a child”, the study of the funds collected and analyzed allows us to deepen our understanding of the experience of children at war, evacuees and/or exiles. They are currently being pursued as part of the Refugee-Childhood Violence Exil (REVE) project.

Throughout their lives, Alfred and Françoise Brauner collected the “drawings-testimonies” of children at war. From 1937, they joined the International Brigades in Spain, she first, as a doctor; he then, with the task of inspecting the centers for children evacuated from the Levantine coast. It was in these homes that the Brauners began to take an interest in drawing as a therapeutic tool, but also a political one, serving to denounce the horrors of war and, even more, to direct international solidarity towards the Spanish Republic.

During the war, it is estimated that around 600,000 total casualties were directly caused by the war, of which more than half were non-combatants. This first humanitarian experience continued on their return to France, with Jewish children evacuated from Germany and Austria, then returning from the camps in 1945. Subsequently, the Brauner’s commitment in favor of “these children who lived the war” is undeniable, whether through the associative action with Enfants Réfugiés du Monde, or through the uninterrupted collection of drawings by children at war, across the century and the continents – from Lebanon to the Iran-Iraq conflict , from Algeria to Vietnam, from Afghanistan to Chechnya…

Of the two thousand drawings kept, the Brauners will retain only a tenth for the book I drew war in 1991, as in the film of the same title produced in 2000 by Alfred Brauner and the documentary filmmaker Guy Baudon.

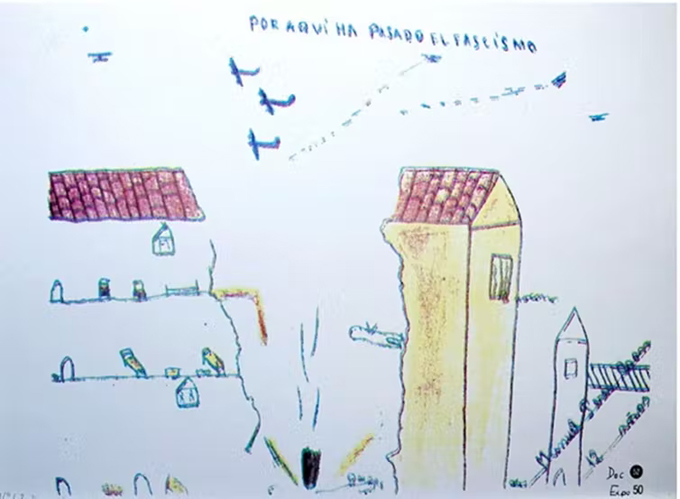

Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Manuel Pérez Osana, 12 years old: “My broken house”. in I drew the war. Le regard de Françoise and Alfred Brauner, Rose Duroux and Catherine Milkovitch-Rioux (eds.), Pubp, 2011, p. 44-45

The Brauners particularly cared for children evacuated to Spain, in Benicàssim in 1938. Alfred Brauner comments: “And you have to look very closely to discover, tiny next to the bomb which has not finished falling, a human figure with the inscription: Padre . It is the reduced dimension of the dead figure of the father which translates the dread. […] At the top of the drawing, the caption-title is political: fascism has been there! »

The originality of the Brauners is to have put children and their discourse on war at the forefront, from their early anti-fascist and anti-Nazi commitments to their later pacifist and anti-nuclear positions, pursuing them in educational contexts. Drawing, as a support for free expression, constitutes a field of experience through which it is a question of asserting the rights of children.

Read battlegrounds

The drawings from the Brauner collection often seem remarkably topical to us. However, we must be wary of a presentist interpretation that reads, for example, the current war of aggression initiated by Russia against Ukraine in the light of the wars of the past, between the 20th and 21st centuries . Each drawing must be placed in its historical context insofar as it bears the imprint of a social world subjected in times of war to singular upheavals, which determine the proper nature and the representation of the experience.

Each drawing must therefore be the subject of a specific reading , which takes into account this production context. The Brauner collection is therefore the subject of a precise description, reproducing both the commentary delivered by Alfred Brauner, himself historically situated, and the descriptive data, sometimes incomplete, available to the research: name of the child, age, place of production, date, format…

The collection of drawings is based both on this description of contextual, factual elements, and on the correlations established between different_ graphic views_ of children; and their reading is also situated in this conjunction ( The R-EVE collections , including the Brauner collection, are deposited and described in the Nakala data warehouse and available from the research blog: “Réfugier Enfance Violence Exil ( R-EVE)”, “Collections”).

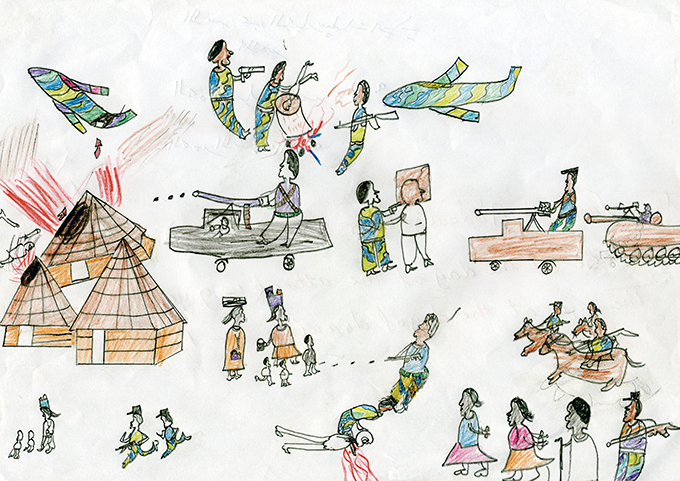

The course of the collection reveals the presence of analogies of themes and composition. Everywhere, we find violence in motion, the emotions it arouses: intrusion of the military, bombardments, bodies, wounds, death, exodus. From European populations to Sahrawis and Asian boat-people, children’s drawings reveal a particular attention for the warlike arsenal, from the machete to the scud, through bayonets, tanks, rocket launchers, and depict the squadrons, shells…

In “Everything is on fire” (Figure 1), two Soviet tanks are burning: a choice that also reveals the patriotic culture in which the Chechen child grows up. In “My Broken House” (Figure 2), Manuel Pérez Osana depicts both fighter and bomber planes, and the trajectory of the bomb exploding on the ground.

Reappropriation through drawing

The imagination of the child designer often applies itself to introducing people likely to bring help to the wounded, stretchers, ambulances, the hospital. These sure supports are first of all those he sees with his own eyes, firefighters, doctors, stretcher-bearers. Manuel Pérez Osana’s drawing explicitly includes a cry for help ( Socorro ), no doubt issued from the point of view of the child, trapped in the bombed and gutted house.

In a more astonishing way, the child stages his own capacity for action – as if, with the drawing, the chaos of war was under control, even if only in an imaginary way. This ability to act can manifest itself in many symbolic forms: in the drawing (Figure 3) “Tulips on the graves”, a Croatian pupil from a kindergarten in the city of Zagreb confronted in 1991 with the bombardments of the army Yugoslav folk depicts graves where civilians and combatants are buried.

With the large tulips, the candles illuminating the tombs – also placed on the rivers in several Slavic traditions – the child seizes the mourning rituals which maintain links between the survivors and the world of the deceased. This reappropriation through drawing is a form of action.

Children’s drawings often invent imaginary representations which constitute so many refuges in a chaotic reality: in 1944, in Terezin, a little Czech Jewish girl, Érika Taussigova, aged 9, drew the dormitory of her stalag with, on the first plan, a fruit basket, a butterfly, and a large vase filled with flowers. On the threshold of death, it opened up an imaginary, intimate and familiar space-refuge, that of the world before.

The collections of children’s drawings, of terrible relevance in the world, bring to our eyes childhood and adolescent experiences of extreme violence. Their collection, preservation, description and analysis make it possible to retrace the history of the scientific, political, humanitarian and artistic uses of graphic testimonies. But also, as Hélène Gaudy writes in the story she devotes to the Terezin camp, An Island, a Fortress , based on drawings by Arthur Goldschmidt (who is an adult), they commit to escaping the surface of things , to “save a part of beauty”: “everything is bare, the faces, the water, the trees, everything exists more.

Author Bio: Catherine Milkovitch-Rioux is Professor of Contemporary Literature at Clermont Auvergne University (UCA)