Waking up in 2025 is weird. Take this morning as just one example.

Waking up in 2025 is weird. Take this morning as just one example.

I open my eyes and immediately fumble for the phone, opening BlueSky and Threads to see what craziness has come out from the USA while I slept here in Australia. Reassuring myself that we are all still alive (well, some of us are) and that the nukes haven’t launched. I figure since I am here now, I might as well continue to doom scroll.

The outrage begins.

This morning it’s news that Meta knowingly used a pirated database of books and academic papers to train its AI. The Atlantic helpfully gives me a search box to see how much of my stuff has been stolen – twice. There’s 15 – shit.

I see my blog post book is there – well ok, not to worry. I wrote that to circulate my ideas and sell it for the cost of a coffee. I’m mildly annoyed that someone was scummy enough to steal it. Then I see my best book is there – Now I’m really annoyed that my publisher somehow didn’t keep it safe.

I see a partial list my academic publications – at least they don’t have the best ones (there’s at least one I wish was never out there in the first place). My outrage settles a bit… this is life now. It’s 2025. The internet. You can’t control it. You can’t control anything.

Then I remember that my own Publisher has sold my stuff to Open AI and didn’t give me a cut. The outrage bubbles up again.

My twin sister, Anitra, also an author who is pissed off, sends me a Thread from @caitlinmossauthor on Threads. who suggests taking credit for Meta’s work by putting “AI creator” in her bio since they used her stuff:

I laugh and make the same change to my Threads profile, adding “Creator of AI (you all stole my stuff).” I change Insta and add pronouns while I am at it. Fuck the facists.

It’s funny, but the joke has teeth. I decide to write a blog post – this idea should travel! Anyone who has had their work stolen should take credit for Meta’s work too!

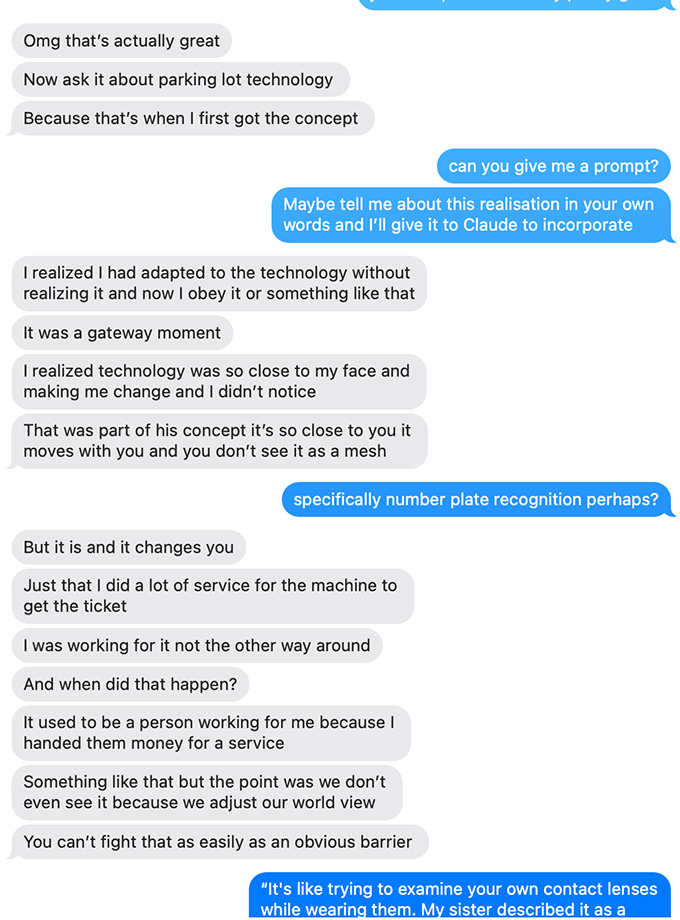

A fun protest – and cheaper than therapy. Anitra agrees and makes a crack on text about the Philosopher Deleuze and his idea of the self conforming mesh:

Now, to be clear, I kind of hate Deleuze. I carry some trauma from my Masters Degree. 1000 Plateaus was the first book of philosophy I had ever been instructed to read and it’s… not a great place to start. (I threw my copy out the door and took a chip of paint off the frame because my aim was so bad. The book still has a dent in it).

But I reluctantly admire the Self Conforming Mesh idea. Deleuze’s concept is hard though. I need help ‘thesis-whisperering’ it. I stare at the blank page for precisely 30 seconds before my fingers, seemingly of their own accord, type “Claude” into my browser.

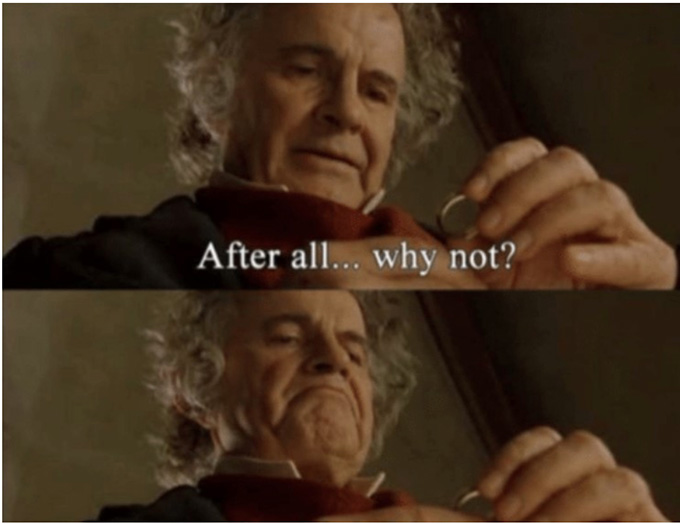

I pause, briefly contemplating the moral whiplash of using AI while simultaneously raging against it. There’s a moment—a very Bilbo Baggins moment—where I hear myself thinking, “After all, why not? Why shouldn’t I use it?”.

I pirated my own book into Claude so I have a useful Thesiswhisperer bot who can write just like me. And now, just like that, I’m annoyed again.

THEY PROBABLY STOLE MY STUFF TO CREATE CLAUDE TOO. THE VERY LEAST THEY COULD DO IS GIVE ME A FREE SUBSCRIPTION. FUCKERS!

I almost expect my face to contort in that unsettling way Ian Holm’s did when he briefly transformed into Gollum.

But unlike the Ring, Claude isn’t slowly corrupting my soul (I hope. I tell myself). It’s just making my work easier, or at least different. Or something. Anyway, just as with doomscrolling, I am here now.

(This casual reaching for AI assistance has become reflexive, unthinking—a habit formed so quickly I barely noticed its installation. This is the mesh at work already. Bloody Deleuze.)

Claude understands the assignment, but it’s first go is a bit academic. I tell it to be more fun, and sarcastic:

You’re right! Your voice typically has more of that fun, sardonic edge to it. Let me try again with that example about your ethical position on AI.

It tries a second time.

Deleuze’s concept of the ‘self-conforming mesh’ is one of those theoretical ideas that sounds impossibly wanky until you realise it perfectly describes your daily academic life. Take my ambivalent relationship with AI.

This morning at 7am, I’m raging about how Meta has scraped my blog to train their models without permission or payment. It’s now 9:30am and I’m asking Claude to help me draft a blog post – but… there’s a lot going on this weekend. I only have an hour to squeeze this out. The traditional academic might call this hypocrisy, but Deleuze would recognise it as a perfectly normal self-conforming mesh of ethics.

Unlike the rigid either/or thinking that dominates academic discourse (you’re either FOR technology or AGAINST it), the mesh allows contradictory positions to co-exist without imploding. My ethical framework isn’t fixed; it bends and reconfigures itself depending on context, need, and frankly, how desperate I am to meet a deadline.

When I rant about AI exploitation while simultaneously exploiting AI, I’m not being inconsistent – I’m embodying the very flexibility that Deleuze celebrated. The mesh doesn’t require logical coherence; it thrives on productive tension. And let’s be honest, isn’t this how most of us actually operate in our scholarly lives, despite our carefully constructed academic personas suggesting otherwise?

I exchange more text messages with Anitra. We laugh at some initial outputs.

I ask her if Claude is right about the self conforming mesh (she knows more about it than me). She says pretty much, and then explains that she only really understood the idea when wrestling with the parking ticket machine:

I fumble in a sort of ok prompt, I guess. After getting it wrong twice (my bad, really) Claude eventually catches the end of the rope:

My sister had one of those rare philosophical “aha” moments in a shopping centre parking lot of all places:

“I realised I had adapted to a technology without realising what was happening,” she told me over text. “There used to be a person, working for me because I handed them money for a service. A machine is there instead and I now work for it. I found myself doing a ridiculous dance for the parking ticket machine—inserting my card, pulling it out too quickly, reinserting it, pressing buttons in a specific sequence, waiting for the beep. This is Deleuze’s self-conforming mesh in action—so close to your face that you can’t see it.”

This IS Deleuze’s self-conforming mesh in action – so close to your face that you can’t see it. It’s like trying to examine your own contact lenses while wearing them. Somewhere along the line, our relationship with technology can flip, and we never even notice the transition. The mesh doesn’t announce itself with trumpets; it quietly reshapes your behaviour until one day you’re standing in a parking lot having an existential crisis about why you’re performing a complicated ritual for a metal box.

This invisibility is precisely what makes the self-conforming mesh so powerful—and potentially troubling. You can fight an obvious barrier, but how do you resist something that has already altered your expectations and movements?

In the past I’ve caught myself restructuring my writing process around word processing software quirks, or designing research questions based on what I think will play well in citation metrics and the endless academic hunger games around grants. The mesh has reshaped my thinking, and like my sister, I only occasionally glimpse it in moments of parking lot clarity when I realise I’m serving a machine rather than the other way around.

I wonder how to bring this blog post to a close. It seems like a cop out to make it neat. So I ask Claude for two specific types of endings. It obliges.

Ending 1: Funny and Charming Justification

And here I am, using an AI to write a blog post about how technology reshapes our thinking without us noticing. The irony isn’t lost on me. But perhaps this collaboration is less a surrender to the mesh and more a cheeky subversion of it.

After all, I’m not mindlessly accepting whatever Claude generates—I’m directing, editing, critiquing, and ultimately deciding what stays. This isn’t blind adaptation; it’s a deliberate dance with technology. I’m using the mesh to examine the mesh. It’s a bit like studying the effects of caffeine while drinking a flat white.

Is this hypocritical? Maybe. Or perhaps it’s the ultimate academic move: simultaneously participating in and critiquing a system from within. Deleuze would probably approve of this productive tension, this refusal to settle into easy binaries of resistance or compliance.

So the next time you find yourself in a complicated relationship with the technologies reshaping academic work, remember you’re not failing at ethical purity—you’re embodying the self-conforming mesh in all its contradictory glory.

And really, isn’t acknowledging our entanglement the first step toward a more conscious engagement with it? At least that’s what I tell myself as I hit “send” on another message to my AI writing companion. We’re all just performing for parking machines in one way or another.

Ending 2: The “Oh Shit” Moment

And here’s where we reach the uncomfortable bit: I’m writing this post about the invisible ways technology reshapes our thinking… using an AI system. The self-conforming mesh isn’t just theoretical—it’s happening right now, in this exchange. Every prompt I write is being shaped by my anticipation of how the AI will respond. My writing style is subtly adapting to what generates the best outputs. I’m outsourcing thinking while writing about the dangers of outsourcing thinking.

Oh shit.

This is the truly insidious nature of Deleuze’s concept—even when we think we’re critically examining it, we’re further entangling ourselves.

I started this post feeling clever about using AI to discuss AI ethics, but now I’m wondering: How much of my thinking has already been altered by these interactions? Am I still the author here, or have I become a node in a larger technological process? The research questions I’m formulating for my next project—are they truly mine, or have they been influenced by what I know works well with the digital tools I have to do it with?

The most disturbing aspect of the self-conforming mesh isn’t that it exists, but that the moment you think you’ve stepped outside it to examine it objectively, you’ve actually just entered a different part of the same mesh.

There is no outside perspective.

As you read this blog post—perhaps while notifications ping in the background, as your reading habits are tracked for future recommendations—ask yourself: Where in your academic life have you adapted without realising? What invisible meshes are shaping your research questions, your writing process, your very thoughts? And the most chilling question: Would you even notice if they were?

Coda

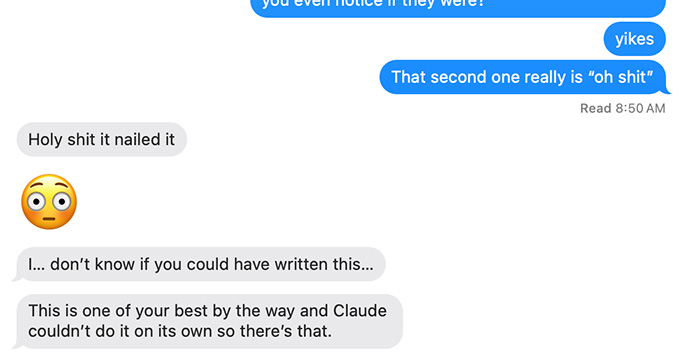

I could end it here, I guess, but I’m a twin and it’s compulsive to share. I give Claude’s responses back to Anitra. We marvel quietly together. She texts:

I know I couldn’t have written it. My sister sums it up: “I love Him. And fear him.” I feel the same way. I pass our final text message exchange back to Claude and ask it to write a coda. It obliges.