A single, pregnant rodent floating on driftwood across the treacherous waters between Asia and New Guinea 8.5 million years ago may be behind the eventual colonisation of native rodents in Australia, our new research suggests.

Today, Australia has more than 60 species of native rodents found nowhere else in the world. When you count their close relatives across New Guinea and island neighbours, there are over 150 species. These include the rakali, an otter-like rodent with webbed feet, and desert hopping mice that get around like tiny kangaroos.

Until now, we’ve had an incomplete picture of how there came to be so many species. Our new research unites genomic sequencing and museum collections to reconstruct the evolutionary tale of native rodents, including many extinct and elusive species – and they have a fascinating origin story.

Native rodents have also suffered the highest rate of recent extinction of any mammal group in Australia, with 11 mainland species declared extinct since European colonisation in 1788. Many surviving native rodents remain at serious risk of extinction, with urgent conservation action needed to secure their future.

The semi-aquatic rakali (Hydromys chrysogaster) is a native rodent distributed across New Guinea and Australia. Rakali are part of the Hydromys Division, a group that has colonised Australia from New Guinea at least twice in the last million years. David Paul/Museums Victoria

New methods, old specimens

We extracted and sequenced DNA from museum specimens collected up to 180 years ago to unlock the secrets of the most elusive species.

In one case, we sequenced DNA from a specimen of Guadalcanal rat from the Solomon Islands collected over 130 years ago. The Guadalcanal rat was last seen alive when these specimens were collected in the 1880s, and hasn’t been recorded since.

It’s listed as critically endangered, and is very possibly already extinct.

Like the Guadalcanal rat, every single specimen we studied has its own fascinating history. Together, they tell an 8-million-year long evolutionary story.

This is a specimen of Gould’s mouse from the Natural History Museum in London. Trustees of the Natural History Museum London/C. Ching

The genetic relatedness of distant rodent relatives tells us the ancestor of Australia’s native rodents originated in southeast Asia. There’s never been a land connection between Asia and New Guinea, and so we know this must happened via over-water colonisation – possibly on a piece of driftwood.

Our research dates this event to around 8.5 million years ago. Both New Guinea and Australia looked very different back then.

In contrast to the large and high-elevation island of modern New Guinea, 8.5 million years ago it was likely made up of a series of smaller, disconnected islands.

Our results show the earliest arriving rodent ancestors, probably tropical forest specialists, initially spread across this earlier New Guinea. But they then stayed put for 3.5 million years.

A shared evolutionary story

Around 5 million years ago, New Guinea experienced a big geological change. Tectonic activity triggered the uplift of an impressive mountain range through the centre of New Guinea, and led to the formation of expansive lowlands.

This expansion opened new environments for rodents to adapt to, and increased connectivity between New Guinea, Australia, and neighbouring islands.

From there, things really took off.

Rodent ancestors first arrived from New Guinea into Australia around 5 million years ago, probably via a land bridge exposed during a period of low sea level.

In Australia, they have adapted to many new environments including the harsh arid desert. In the last few million years, rodents have been especially mobile – repeatedly moving between New Guinea, Australia and neighbouring island archipelagos, generating many new species in the process.

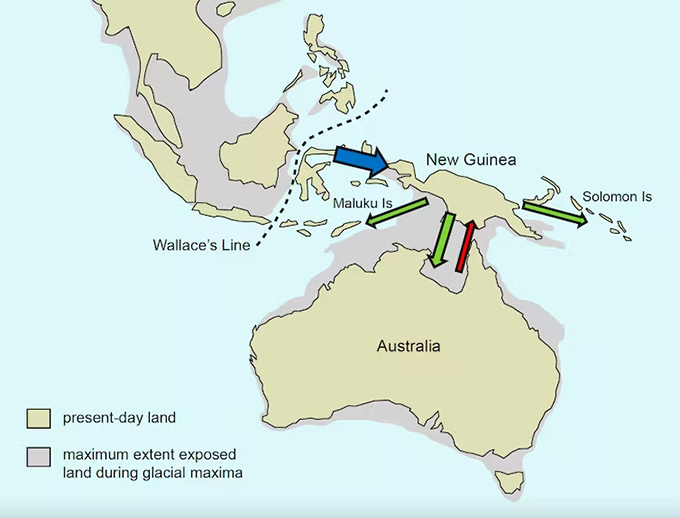

Native rodents first arrived to New Guinea from Asia 8.5 million years ago, and then arrived to Australia 5 million years ago. Over the past few million years, they also have spread across the Solomon and Maluku Island archipelagos.

In our region alone rodents have transitioned between different geographic areas or islands at least 24 independent times in the past 5 million years.

Quite often, this has happened via over-water colonisation. Just like their ancestor, who crossed the waters from southeast Asia 8.5 million years ago, native rodents have continued to leverage their impressive rafting skills.

And yet, despite this remarkable flexibility across evolutionary time, native rodents have not been able to tolerate the dramatic changes to their environment that have occurred in the past 200 years.

Protecting native rodents

Since 1788, we’ve lost 11 native rodent species to extinction. These include the white-footed rabbit-rat and the lesser stick-nest rat, once common on the Australian landscape.

Native rodents are particularly susceptible to predation by feral cats and foxes, land clearing, competition with pest rodents, and introduced disease. These ongoing threats place surviving species at serious risk of extinction.

One of Australia’s most critically endangered mammals, the central rock-rat, is on the brink of extinction after extensive habitat loss and predation by cats and foxes. Captive breeding programs are underway to boost population numbers.

A smoky mouse (Pseudomys fumeus) in the Grampians-Gariwerd National Park, Victoria, Australia. The smoky mouse is part of an evolutionary group that originated after colonisation of Australia from New Guinea around 5 million years ago, and is currently endangered after suffering population declines. David Paul/Museums Victoria

We know even less about the conservation status of many species in New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Maluku Islands.

By combining genetic data from both modern and historical specimens, our new research takes stock of the diversity of native rodents, and will help to define and prioritise species for conservation efforts.

By understanding how our native rodents evolved, we can make more informed decisions about how best to protect them into the future.

Author Bio: Emily Roycroft is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Australian National University