For the last 20 years I’ve been on a quest to find the perfect academic note taking system.

I abandoned paper in 2005 when I realised my notebooks were the place my ideas went to die. Although writing into a notebook felt useful at the time it was hard to find stuff later. Flipping fruitlessly through hundreds of pages of bad hand writing was frustrating. When I did find the notes, they didn’t make much sense without the source material. Scribbling notes on printouts solved this problem and created another: filing. I’d either remember the author or the title – maybe sometimes just the topic or idea. You can’t file a piece of paper under four categories at once.

I’ll admit, over the last fifteen years, I’ve wondered at people who cling stubbornly to their paper ways. Digital notes have all sorts of obvious advantages. The search function replaces filing and you virtually eliminate the ‘transaction cost’ of transcribing notes from paper to screen. It all sounds great – but there’s a reason there’s heaps of database products on the market and none have dominated. They don’t really solve the note taking problem.

I’ve been a relentless digital note taking booster, but I have a confession to make. All the time I was telling people that digital notes were better, I had the nagging suspicion something was not working. I frequently found myself overwhelmed when I sat down to write. I had everything I needed, but the annotations and slabs of text I’d accumulated just didn’t seem that useful.

This is not a tool problem. I say this after trying and discarding almost every digital tool on the market.

In an attempt to replicate the success I had with writing on printouts, I’ve taken notes in a bunch of conventional citation managers: Endnote, Zotero, Mendeley and Papers2. I felt even more scattered taking notes this way than I did writing in a notebook. By splintering my notes, I splintered my thinking.

The next step was to try digital databases. Theoretically, a database can help you find relationships and connections. By running a search, you can see related things together and spark ideas. I’ve used many databases – Evernote, DevonThink, OneNote, Readwise, Pocket and Notion just to name a few. To be honest with you, even though I have briefly evangelised some of these products, I’m unconvinced any are worth the effort.

Some databases have great features – like the machine learning assisted searching in Devon Think – but maintaining a notes database properly is a lot of work. The best thing about digital databases is also the biggest problem: they are frictionless. By enabling you to store, and move data around, effortlessly, it’s oh so easy to put a lot of stuff in there without an organising principle.

The end result? Information Indigestion.

Unless you are very careful about naming conventions, tagging and pruning, your notes quickly become a hot mess of digital clutter. I’ve come to the conclusion that a notes database you spend a lot of time managing is worse than a notebook you never read.

Note taking is basically a way of squeezing insights out of information: the process is often more important than the product itself. This doesn’t mean notes are pointless, but it’s important to remember they are a means, not an end. The ‘meat computer’ on top of our necks is pretty good at making connections and ideas. Notes are there to help.

My best advice is to let go of the need to have a perfect ‘system’ and develop a ‘good enough’ set of solutions that work for you. Below is a set of notes on how I take notes. It’s not pretty, but it works.

I don’t suggest you adopt ‘my system’ – because it’s not a system. It’s a bunch of hacks and work arounds. Maybe some of them will be useful to you. Or maybe, by sharing how messy I am behind the scenes, you will feel better about your own ad hoc solutions!

Notes for writing

One of the key things we teach at our world famous thesis bootcamp program is how to write without constantly rummaging around for notes. People reach for their notes in an attempt to make sentences perfectly correct the first time. But all this rummaging derails the creative process. People can write four or five times faster by free writing first, and using their notes to check information later.

The notes you need for writing are more than just what you’ve read: you need to process ideas, facts, findings and insights from data. I find the best way to take notes for writing is to write them straight into a file: one that has a name and a specific purpose. The file acts as a grounding tool to focus the note taking. I write the actual notes either as a comment, or in a different font. These notes are really premade ‘chunks’ of text for the final paper. Think whole sentences with subjects, objects and verbs. I weave these notes into the writing as I generate text and edit.

If you want to try this ‘just in time’ approach, it’s best to use a fit for purpose tool like Scrivener. Scrivener has a built in notes pane next to your main text. It also has the capacity to store PDF files with the text so a curated list of relevant source material is always available as you write. In this way, Scrivener helps you digitally replicate the ‘scribble on the side of a print out’ type of note taking.

Scrivener helps a lot, but you will still end up with a splintered note problem. Every piece of writing becomes a digital version of a bulging manila folder, full of newspaper clippings. Some of those clippings are potentially useful in other projects, but they are now locked in a file. You can’t search the notes in multiple Scrivener files at once… but hey, good enough, right?

Notes for your literature review

Literature reviews require a special kind of note taking. These days, the literature on anything, even a tiny field like mine, is vast and anxiety provoking. You must read and synthesise vast amounts of information. You won’t use everything you read, at least directly, and part of the job is to decide what is relevant to include in the text and what will remain in the background. Sometimes people produce an extended bibliography that includes things they read, but didn’t cite, so keeping track of what you decided not to use can be important.

You’ll need a couple of specialised literature wrangling tools in your belt.

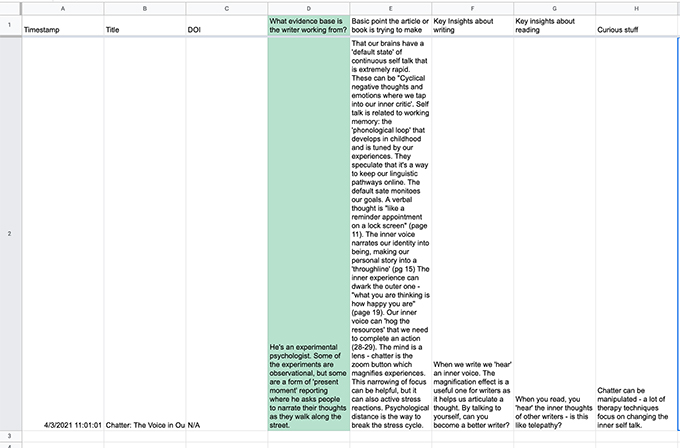

While some people like the Cornell template to turn notes into writing, I prefer the literature review matrix method: an idea I picked up originally from the ‘My Studious life’ blog. A literature review matrix is simply a table with the individual paper names as the columns and questions you are trying to answer as rows (if you are having trouble imagining what I’m talking about, there’s a live example here). The advantage of a matrix is it’s cumulative – you can add columns as you read and synthesize the insights by simply reading along the rows to compare what different authors said about the same thing. This method is excellent for spotting areas where the literature is sparse, because some rows simply get more fleshed out than others.

Katherine Firth, Shaun Lehmann and I subsequently documented this idea and some variations more fully in two books: How to fix your academic writing trouble and Level up your essays. I have a free cheat sheet for the method here. I use google sheets to make them as I find Excel and MS Word have too many formatting issues. But lately I’ve been experimenting with using Google forms for long term projects. The form helps me capture the ideas sequentially:

And then auto-generates a matrix you can review to see where ideas intersect:

This is kind of a nifty cross between the cornell note taking method, which helps you structure your thinking, and the matrix method, which highlights relationships between things.

I’m excited by new tools that work on a social graph principle, like the amazing Connected Papers. I think this is the future of literature reviewing in an age of endless information and I am here for it!

Notes for teaching and presentations

Presentation notes are extremely valuable. This kind of hybrid writing/note taking practice is very audience focussed. Teaching forces you to think about sequencing and comprehension. Presentations force you to think about how to make your ideas into stories. If you are really stuck on a piece of writing, a good trick can be to make a powerpoint presentation and write notes under it.

My principle here is to take the path of least resistence. I simply write everything on the slide, then transfer most of it to the notes pane so I don’t end up with a wall of text. Invariably, I end up recycling those notes back into papers and articles. For high stakes talks, or when I am not as across the material as I would like to be, I make a written script in plain language – these are even more useful. Here’s the script I used for my PhD confirmation, which I immediately turned into my introduction chapter.

Notes not bound to a task or project

Like all academics, I’m a curious person and like to read stuff in my areas of interest for no particular purpose – other than idle nerdery. I want to record some of this reading, but I don’t want to invest too much effort in the note taking process. Notes with no obvious purpose are the most difficult to manage. They are why a database still has a place in your arsenal of organising tools. In fact, you’ll probably need more than one database tool to manage academic work.

I use Pocket to clip things from the web and I don’t even bother tagging or filing this information. I indiscriminately grab everything interesting, then run a search in there if I have a specific problem to solve. I am still using OmniFocus to organise my email and projects, and I use the notes pane there to take notes of meetings.

I use Notion to keep my professional contact list organised. I think this is the best of the structured databases I’ve tried because it’s essentially a personal wikipedia. I don’t use Notion for my own notes as I have gone back to hand writing (see below), but if you hate hand writing, like my son, it’s worth a try. I introduced Thesiswhisperer Jnr to Notion when he started Uni and he happily uses it for all his lecture notes. I have observed him turning these notes into writing and it seems to work well for that purpose.

For a long time I used Endnote for random thoughts and ideas, but lately retired it because paper works just as well – maybe even better (gasp!). My friend and ‘On the Reg’ Podcast colleague, Dr Jason Downs started using the Bullet Journal method or #bujo. I always copy Jason, so I bought myself a notebook, sharpened a pencil and got to work.

I’ve found the #bujo extremely useful for jotting notes, drawing diagrams and maintaining daily to do lists. I often write notes in there that I end up transfering into presentations and papers. It’s not the purpose of this post to tell you exactly how to implement the #bujo method for yourself. There are vast amounts written about it and some helpful videos on the Bullet Journal Youtube channel, like this one:

My only #bujo suggestion is to start simply.

The key difference between the #bujo and a normal notebookis that a #bujo has numbered pages and an index at the front. Even if you only implement this page numbering principle, it will make your notebooks 1000 times more useful and no longer the place where ideas go to die! If you want to hear more about the #bujo method, tune in to the On The Reg podcast that was released in early April – Jason and I discuss it at length.

I hope this extended meditation on the note taking process was useful for you. I’m interested in your hacks and solutions so I’ve turned the comments on for this one. If you are interested in sharing your own hacks, or chat to me on Twitter.

In note taking solidarity!