We have to talk about ChatGPT, or as my sister @anitranot styles it, ‘ChattieG.’ (which is both funnier and easier to say).

The reaction to Chattie in academia seems to oscillate between moral panic (“OMG, The Youngs will cheat on their assignments!!”) and world-weary cynicism (“it writes like shit anyway”). Very few people seem to be talking about ChattieG in the context of the Academic Hunger Games, by which I mean the competitive/toxic race to produce more and more publications and ‘get ahead’. Chattie is a new weapon in our backpack, how should we use it?

Honestly, I’m a bit perplexed by academics’ reactions to this technology. Some are vocal abstainers, claiming “It’s not that good anyway” (they’re wrong – it is), or that it takes the ‘joy’ out of writing (personally, I don’t find academic writing that joyful, but your mileage may vary). Other academics have embraced it, but, perhaps due to the ‘death of the blogs’, are not documenting their use publicly.

In my opinion, we’re in desperate need of more public discussion about how this tool fits into an academic writing workflow. The wonderful Mark Carrigan is writing a book, but I’m too impatient, so I thought I’d start the ball rolling. I don’t consider myself an expert user, but I have been sharing my tricks in the classroom this year. People seem to receive my lessons well and have encouraged me to document some of my hacks. So this post showcases my favorite ChatGPT prompts for writing.

I can’t talk about Chattie without talking about ethics. To be crystal clear: SOME OF WHAT I AM GOING TO SAY IS NOT OFFICIALLY APPROVED USE OF CHATTIEG FOR STUDENTS AT ANU. Important People in the university are working on a set of principles that will be released in the new year. It’s my understanding these principles will apply to both staff and students. The official advice from ANU management – at the moment – is that PhD students can use Chattie in the way they could use a human editor.

This guidance may change soon, but it has the advantage of being quite clear in the meantime. There are specific limits on what human editors can and can’t do to dissertation text, which are set out in the Australian Standards for Editorial Practice. I’ll let you know which of my prompts comply with these guidelines. Your university will have some guidance, so check anything you aren’t sure about with the appropriate authorities. And don’t forget that journals are starting to publish their own guidelines, see for example Elsevier (the relevant section is about halfway down the page).

Before I begin, a note on how ChattieG or any large language model functions:

The more information you give ChatGPT about the task, the better the results will be. Ethan Mollick, the best writer I have found on the topic, talks about ChatGPT like this:

“You can (inaccurately but usefully) imagine the AI’s knowledge as a huge cloud. In one corner of that cloud, the AI answers only in Shakespearean sonnets, in another, it answers as a mortgage broker, in a third, it draws mostly on mathematical formulas from high school textbooks. By default, the AI gives you answers from the center of the cloud, the most likely answers to the question for the average person. You can, by providing context, push the AI to a more interesting corner of its knowledge, resulting in you getting more unique answers that might better fit your questions” Ethan Mollick, One Useful Thing blog

When you create a ChatGPT account, you will be asked how you wish the tool to behave and talk to you. Telling ChatGPT to act like your research assistant generates default text from the ‘academic speak’ part of the cloud.

“Summarize these notes.” Producing short summaries is part of the Cornell template method, a useful technique for making neater, more searchable notes, and the so-called Zettelkasten. You can put the text summaries you produce with ChattieG in your bibliographic database (I use Zotero), or in a notes database like Obsidian… or even in an Excel spreadsheet (but please don’t do this).

Producing summaries helps you search your notes to find similarities between ideas and findings. Have a look at this example of me cleaning up some notes from Zotero. So long as you use this text for indexing purposes and do not directly import the words, it falls under acceptable use for PhD students at ANU.

“Clean up this audio transcript, fix mistakes, and make it shorter.” (thanks to John Milne for this idea): There are many tools that will produce an automatic transcription from a recording (I use Descript, but even Microsoft Teams will do this for you now). If you like to talk your notes instead of writing them, or you like to record discussions with collaborators, making sound into text is obviously useful. This prompt does a bang-up job – have a look at what it does to a bit of a transcript from the podcast I do with Jason Downs, ‘On the Reg’.

The problem with these transcription tools is they are geared for American accents and a bit glitchy. Also, spoken language is more ‘wordy’ than written language, so getting ChatGPT to make the transcription shorter makes the editing process more efficient.

I think this is acceptable use of ChatGPT as it’s primarily processing text, not correcting or editing, but it’s an example of how difficult it is to make blanket prescriptions as you couldn’t ask a human editor to perform this task. You can also use this technique on qualitative interview transcriptions, but check the privacy settings to make sure the transcript is not ‘swallowed’ by the tool – there have been some recent reports of ChattieG hacking that can elicit original training text in the prompt window.

“Re-write this text, but in plain language at a ninth-grade level.” Researchers often have to present their work, but if you read out academic text it sounds awkward, wordy, and long. There are lots of technical reasons for this, including left and right-branching syntax and nominalisation, but this is not a post about language. Suffice to say, this prompt can start you on the process of producing a conference script or presentation from a densely written academic text. Again, I think this is an acceptable use for both working academics and PhD students as you’re using it to translate text for a different purpose, not editing or generating text.

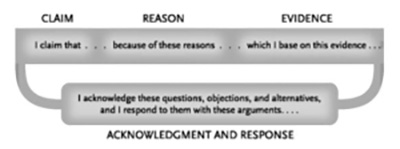

“Criticize this text from the point of view of someone who doesn’t believe (insert your key argument).” One of the keys to good academic writing is anticipating the readers’ objections and questions. If you make an effort to raise and answer these imagined questions and objections in text, it will be more persuasive. Novice writers often forget or don’t do enough of this ‘reader anticipating,’ which is why their text is often unconvincing (for more on this, have a look at these teaching notes on writing better paragraphs). Honestly, I could write a whole post about this, but have a look at the writing advice in ‘The Craft of Research,’ from which I took this handy diagram of how to construct paragraphs:

Essentially, this prompt is asking ChatGPT to act like a supervisor: questioning your propositions so that you can develop more convincing arguments. I’ve never used the text it produces directly; instead, this prompt is a creative tool to test my ideas. You cannot ask a human editor to do this on your thesis, so technically, this use of ChatGPT falls outside of the current ANU guidelines for appropriate use by PhD students.

However, as a working academic who doesn’t always have colleagues willing to read and critique my work, I find this prompt invaluable. The imagination required to anticipate readers’ responses is an academic superpower, requiring cognitive flexibility and knowledge of other literatures. It’s probably not a good idea to get too reliant on this feature: as they say, use it or lose it. On the other hand, imagination can be in short supply when you are overwhelmed, isolated, or just so deep in the weeds that you have lost perspective.

“Can you peer-review this text for me, look for logical argumentation problems?” Similarly to the previous prompt, this one is asking ChatGPT to perform the role of supervisor or mentor and therefore not appropriate for ANU thesis writers. However, for me, it’s pure gold. ChatGPT is surprisingly good at actually naming the logical errors, and I would rather hear it from a machine than get a desk reject for my paper.

“Now pretend you are an academic in (insert discipline) – ask me six difficult questions about this text” / “You a person who doesn’t believe (your key proposition), now ask me five difficult questions”: Some academic disciplines are notorious for asking really hard questions when students present at conferences (looking at you Economics. Yes – you). Worse, curly questions can really derail you during an oral examination or viva. One of the best ways to prepare for questions is to convene a panel of clever friends and colleagues and ask them to grill you. Unfortunately, convening a panel is not always practical. ChatGPT is a good stand-in for a scary audience.

Have a look at this prompt exchange I used to test out my conference script for SRHE in Birmingham. It’s not perfect, but honestly, it’s quite close. Is this fair use for students according to the advice from ANU outlined at the start? It’s hard to say because while this prompt is asking ChatGPT to act like a supervisor, not a thesis editor. However, the text it’s producing is meant to help you prepare for a performance, not write your thesis. I think it’s a good example of the difficulty of making blanket guidelines around this technology.

Finally, don’t forget “proofread this text and correct errors”: I ran this blog post through ChatGPT, and it found a few! Totally ok use for students under the ANU advice and quicker than trying to do it myself.

OK, I’m on the road in the UK at the moment, so this is all I have time for. I have many more prompts, which I am happy to share in another post if people are interested.