Orientation is a source of considerable stress for young people. If it is often at the end of the school year, during the dissemination of post-baccalaureate admission results, that public opinion becomes aware of it, this phenomenon goes well beyond the deadlines of the end of the school year. It would affect two thirds of young people aged 18 to 25, according to a survey conducted by CREDOC (Research Center for the Study and Observation of Living Conditions) for CNSECO (National Council for the Evaluation of the School System).

Although the stress seems to increase as the final year approaches, middle school students are already massively expressing their difficulties in the face of these choices for the future .

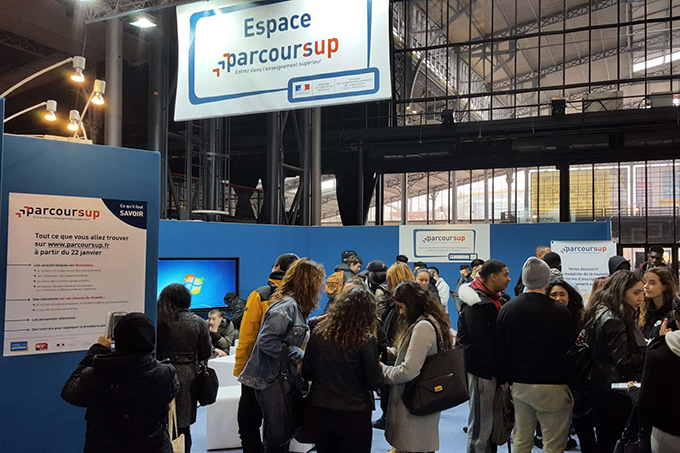

As high school students receive from June 1, 2023 on Parcoursup the first responses to their applications for enrollment in higher education, let us ask ourselves what orientation represents for the new generations.

While many systems are in place to help students build their careers, we generally continue to focus on issues of school, university, or socio-professional integration. We often forget the specificity of the time in which these deadlines fall, adolescence, which affects the way of considering future projects.

Orientation, an important step towards adulthood

The choice of orientation often marks one of the first assumptions of responsibility for adolescents. Associated with the development of their autonomy, it implies a distancing from the parents, and therefore the loss of their protection. Apprehensions about the future are even stronger when students feel helpless in the face of the complexity of courses and procedures or have a level that is too low.

Young people frequently complain about the unfairness of guidance systems , and their distress can therefore be mixed with a feeling of anger. Without prejudging its merits, this complaint challenges the institution and, through it, the adults, both criticized and sought after during this process of empowerment.

Although the choices of orientation are less dependent than before on social and family traditions, through them, adolescents nevertheless situate themselves in a filiation by affirming their proximity to a member of their entourage exercising in the path envisaged or expressing his interest. from his view. This is why the enhancement provided by admission to a course is also a way of hoping to satisfy the people who are important to them.

“To be taken”, “to be refused”, “to know if they want me” are all expressions that young people use to express their concerns. Consequently, the choices of orientation involve the construction of the self-image on several levels. First of all, their program reflects the idea that adolescents have of themselves according to, in particular, their confidence, their social characteristics, their femininity/masculinity , as Françoise Vouillot develops in particular.

The answers they receive in turn shape their representation of themselves. Not only do they strengthen or weaken their self-confidence but they consolidate, or on the contrary, call into question their identity, since through them, the social space makes a judgment on the adequacy of their personality with the place envisaged.

Choose and affirm your identity

The elaboration of an orientation project is indeed similar to that of an “identity project” according to the formula of Piera Aulagnier . With him, the teenager seeks to identify his desires , to affirm them, to have them recognized. The project thus allows him to authenticate himself by evoking his dreams, his ideals, his desires, but also their limitations. However, it remains subject to social recognition, through selection and graduation.

In other words, while the project represents an opportunity for the adolescent to speak out on his behalf by stating how he wishes to position himself in collective life, admission or refusal to the requested sector supports or, at the contrary, dismisses this attempt to affirm oneself as a person.

However, not all forms of stress are created equal. Some relate more to the fear of lacking information on the existing paths, on the openings or on the daily life of a professional activity. According to our observations in the field, resulting from our research on the experience of orientation carried out in schools of different academies, these concerns are more significant among pupils or students from underprivileged social backgrounds. Focused on functioning and social expectations, they refer to a lack of external benchmarks.

Mixed with these preoccupations is a quest for internal landmarks undermined in adolescence with physical and psychological transformations. From this angle, orientation stress could be reclassified as anxiety. With him, it is finally about the anguish linked to the risk of losing the love and esteem of his family by not being up to expectations, of the anguish faced with the responsibility of affirming his desires in the face of social demands, of the anguish of “who am I? »

Some situations amplify this identity anxiety, such as the case where adolescents are more fragile psychically. Similarly, pupils “directed by default” or subject to “an involuntary orientation”, already experiencing difficulties at school, do not manage to feel recognized when they state their projects, to the point for some of them of asserting “not having a future or “to be good for nothing”.

This anxiety can still be oppressive for students from disadvantaged social backgrounds who feel stuck in a hopeless future, but also trying for students from privileged social backgrounds who are subject to demanding pressures. Finally, it can be fueled by the assignment to a social, cultural or medical stigma , which subjects adolescents to the plans of others for them, dispossessing them of their future. Thus, as we were able to show in a previous article, although students with disabilities are regularly encouraged to state their plans for the future, their words are ultimately little taken into account.

Dreams to be reconciled with the challenges of the contemporary world

Inherent in the process of adolescence, the anxiety of the choice of the future is particularly strong when environmental , social or geopolitical concerns rise, making it difficult to project into the future, and therefore, the dreams of youth. But dreams are fundamental in adolescence . By providing a protected space, they allow time to grow and imagine a way to present themselves to others before they can face the encounter with reality.

However, the context does not exempt us from questioning the responsibility of adults. It might seem paradoxical that the stress or anxiety increases at the very moment when the institution aspires to develop benevolent educational practices. In this sense, Pierre Boutinet notices the contradiction of an institutional position which encourages pupils and students to express choices only to finally not really take them into account . The projects envisaged are immediately confronted with the threatening reality of the weight of grades, the number of places in institutions and the lack of outlets.

In short, the requirement of performance encourages the development of academic, professional and social skills in order to master orientation. But the discourse carrying promises of emancipation at work does not take into account the concerns of adolescents by remaining focused on the idea that a “good orientation” would ensure the future.

This discourse could, however, run out of steam with the succession of social crises and employment crises, or even with the development of suffering at work . For the time being, by avoiding the intimate questioning of adolescents, the risk is not to consider them through their personal history, but as pupils or students who can be changed over and are malleable at will.

Author Bio: Dominique Meloni is a Lecturer in Educational Sciences, specializing in educational psychology. Clinical Psychologist at the University of Picardie Jules Verne (UPJV)