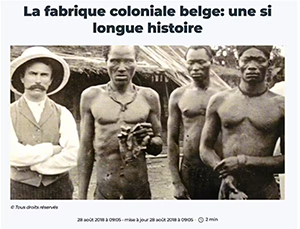

Every day, images related to historical events are put online without being referenced – with their author, date, location, place of conservation – and even less contextualized by a historical commentary. This is the case, for example, of this photograph , most often published to represent the exactions of the “cut off hands” in the Congo of Leopold II, at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century. In 2024, we find it on thousands of web pages without the author of this photograph always being mentioned and without being the subject of an appropriate historical commentary.

Photo illustrating an RTBF article in 2018.

This photograph seems to illustrate in a striking way the atrocities committed by the rubber companies in the Congo. But what can we see in this photograph without knowing its history? The viewer is here forced to interpret the photographic message through the filter of his own representations, seized by the contrast between the victims and the Europeans dressed in white down to their colonial helmets, who seem to justify corporal punishment by their hieratic pose.

In reality, this photograph was taken in 1904 by a Protestant missionary, Alice Seeley Harris , to denounce this violence and the two men in the photograph participate in this act of photographic resistance that will contribute to mobilizing European public opinion against the crimes committed in the Congo Free State. The identity and intentions of the photographer are not a detail here: they reflect a more complex historical reality, that of a “moral polyphony” of European societies at the end of the 19th century , divided on the merits and excesses of colonization.

A digital fog of decontextualized images

There are thousands of examples like this on the web, with publications and image sharing generating a fog of decontextualized photographs, made viral by the algorithms of search engines and digital social networks.

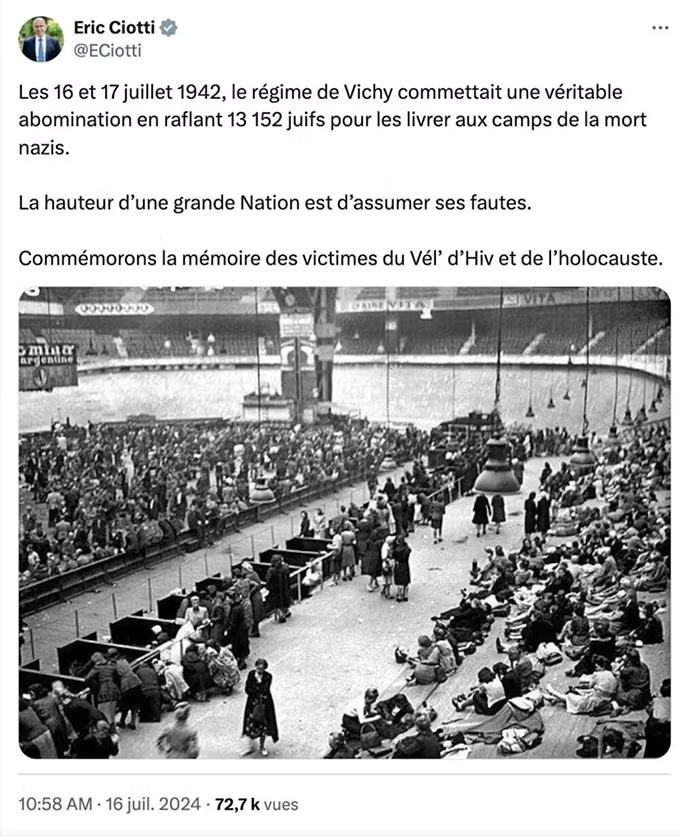

Let’s take the example of this tweet from Eric Ciotti posted on July 16, 2024 in commemoration of the Vel d’Hiv roundup:

Screenshot.

The photograph posted has little to do with the roundups of July 16 and 17, 1942: it is in fact a snapshot showing French people suspected of collaboration locked up in the Vel d’Hiv after the Liberation. This Twitter account is not the only one to reproduce this error; it should be noted that Google images algorithms have long placed this photograph in the first search results following the keywords “Vel d’Hiv roundup”.

Is the correction of this error only the business of historians concerned with identifying sources? In reality, this error contributes to the historical ignorance of the Vel d’Hiv roundup. As historian Laurent Joly shows, there is only one photograph of the roundup , taken on July 16, 1942 for propaganda purposes and yet never published in the press. This detail is not insignificant, it reveals that the German authorities banned the publication of photographs of the roundup, alerted by the disapproval of the Parisian population.

A challenge for teachers

These few examples should alert us to the illustrative use of photography, which is still too present in school publishing. Due to lack of space, textbooks are most often content with a simple caption without commentary to clarify or confirm the teacher’s lesson.

The use of photographs by historians has nevertheless evolved in recent years, now considering them as real archives to which the elementary rules of source criticism must apply. Such use would certainly benefit from being generalized in the teaching of history to raise students’ awareness of documentary criticism – most often summarized by the SANDI method (Source, Author, Nature, Date, Intention). Because, if this method is sometimes considered artificial by students , it finds a justification, so to speak immediate, in the criticism of the photographic archive.

Indeed, the way students view the photographic image changes radically once they know its history .

This documentary approach is all the more necessary as pupils and students today increasingly obtain their information from social networks , networks where photographs are relayed by armies of accounts without methodological scruples and sometimes oriented by conspiratorial readings of the past.

Another piece of data must be added to understand the educational challenge that awaits history teachers in the years to come: by 2026, according to a Europol report , the majority of content available on the web will be generated by AI. This will probably involve the publication of increasingly credible and sophisticated fake photographs, which will serve as proof for fiction disguised as history.

The proliferation of generative AIs and the acceleration of the exchange of invented, diverted or decontextualized photographs constitute a real educational challenge. How can we teach history to students without giving them the tools to confront historical disinformation online? How can we explain to students the digital environment in which they are immersed (AI, algorithms, vitality of images) without offering a history course that is also a digital history course ?

A project to combat the virality of historical disinformation

To meet these challenges, the Encyclopedia of Digital History of Europe ( EHNE-Sorbonne University ) and the IT teams at CERES-Sorbonne University are developing a new tool aimed at teachers, publishers and journalists: the VIRAPIC project , a digital platform whose objective is to identify viral photographs (reproduced online on a very large scale and/or over a short period of time) when they are invented, diverted or decontextualized from the historical events they claim to illustrate.

The objective is twofold. It involves injecting historical content around viral photographs (source, caption, historical commentary) and analyzing the digital virality of photographs (Who publishes them? On which media? With what temporality?). The VIRAPIC project mainly addresses the problem of historical disinformation through a pragmatic approach: fighting against the virality of disinformation by referencing historical work on search engines.

The originality of this tool lies in the possibility of acting directly on the practices of Internet users thanks to the referencing of the EHNE Encyclopedia, whose web pages appear in the first results of search engines. Thus, Internet users looking for photographs to illustrate historical events will see the EHNE/VIRAPIC web pages appear in the first search results such as Google Images.

By creating a reference base for viral, diverted, decontextualized or invented photographs around historical events, the VIRAPIC project will provide rapid access to solid and critical historical content on the images that students, teachers or publishers wish to publish online or use in class.

Author Bios: Mathieu Marly is Editorial manager of the Digital History Encyclopedia of Europe (Sorbonne University – National Education), associate professor, doctor of contemporary history and associate researcher at the SIRICE laboratory and Gael Lejeune is a Lecturer-Researcher both at Sorbonne University