When was the last time you read a good book? If it was quite a while ago you might want to head to the library or the nearest bookstore, because research shows that reading makes you happier. In fact, adults who read books regularly are on average more satisfied with life, and more likely to feel that the things they do are worthwhile.

Research has also revealed that reading for pleasure can be a key factor in children’s levels of happiness. It has been shown that reading is more important for children’s cognitive development than their parents’ level of education. And is also a more powerful factor in terms of life achievements than socioeconomic background.

Yet despite all the benefits reading can bring, statistics from 2014 show that one in five children in England cannot read well by the age of 11. And with this in mind, anything that helps to encourage children to read is often seen as a good thing.

Personalised reading

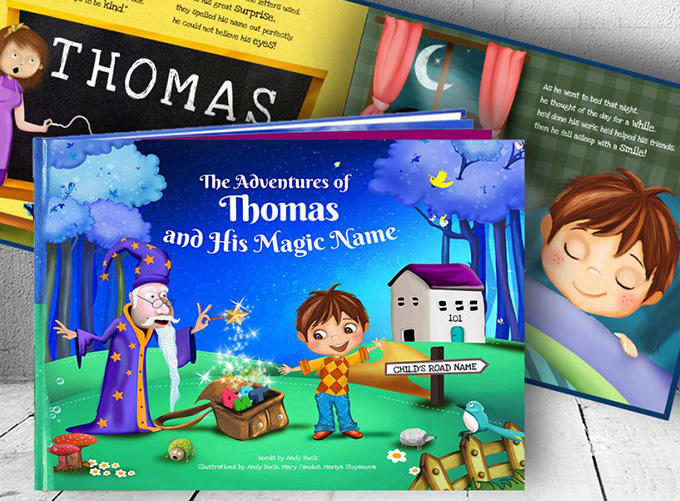

Over the years, personalised children’s books have become increasingly popular. This is when children’s names, addresses, their likes and dislikes are inserted into a story book – the characters can even look like the children. These books are sold online and have become big business with many new children’s publishers popping up creating these one of a kind story books.

‘It’s all about me’. Shutterstock

Wonderbly, one of the biggest publishers of personalised books, has sold over 2.7 million copies of their leading title “The Little Boy/Girl Who Lost His/Her Name”. Children tend to like personalised books because they are specially made for them and often feature themselves or their friends and family members as story heroes. And reading a personalised book together can be a really lovely experience for parents and children.

But personalising books in this way means that how children’s publishers work is now changing. Because as well as producing books, they are now also data managers – responsible for the privacy and confidentiality of children’s data.

Privacy fears

There are no official national guidelines regarding the amount, storage or sharing of data collected by publishers and producers of personalised books, so parents must trust the integrity of individual companies and that their family data won’t be misused or misplaced. This data often includes information such as a child’s date of birth, gender, address and photographs.

The way children are reading books is changing. Pexels.

Though some progress is being made – from May 2018 the General Data Protection Regulation will apply throughout the EU (including the UK) – it is still the case that children’s personal data can become ensnared in a web of complex legal and technical challenges if it is ever reused, consolidated, or organised by publishing companies.

Interviews with UK children’s publishers and app designers also show that many handle large amounts of children’s personal data, but don’t necessarily know how to use it effectively.

Making data safe again

This is why the UCL Institute of Education is developing new personalised reading technologies and also working to address the challenges of personalised books.

As part of the project we are working with the HAT Community Foundation and the The Hub of All Things – a technology designed to help the internet exchange and trade personal data. HATs are “private data accounts” that let anyone store their personal data for themselves, so that they don’t have to rely on governments or corporations.

As we explain in our white paper, if publishers use HAT technology, a child’s private data account could hold their personal data in a contained, self-owned database. This means that children and their guardians would be able to own their personal database in the same way they own physical assets, and share the data within it on terms they control.

Changing the way this data is stored and used is important because there is a big future for these types of books. And it is clear that children’s publishers need a straightforward means of effectively leveraging personalisation – both economically and educationally – to improve both the reading experiences of children, and the peace of mind of their parents.

Author Bio: Natalia Kucirkova is a Senior research associate at UCL