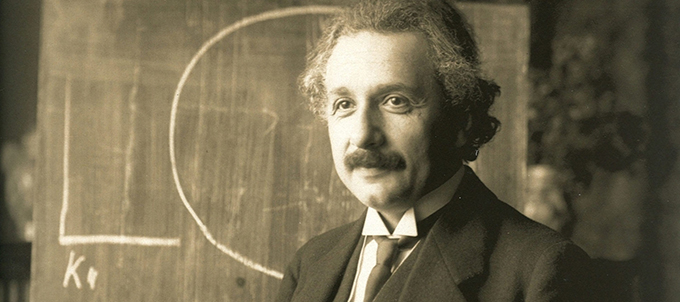

If we were to ask people on the street for the name of a scientist, the answers would mostly be divided between Albert Einstein , Marie Curie , Isaac Newton , Stephen Hawking and local scientists, such as Santiago Ramón y Cajal , or those who appeared in films, such as Robert Oppenheimer .

According to some polls , the first four would get approximately between 60% and 90% of the responses, and Albert Einstein would be the clear winner.

Now, if we were to ask why they know Einstein, the vast majority of those surveyed would answer “the theory of relativity !”, even if they didn’t know what that theory was about… We would agree that Einstein contributed to the progress of science with this achievement, although he also did so in other, less well-known areas that are of great importance in our daily lives.

Four pioneering articles

In 1905, before publishing his most renowned theory, Albert Einstein published four articles , each of which was worthy of the Nobel Prize:

- On a heuristic point of view on the production and transformation of light , in which he proposed quanta of energy and explained the photoelectric effect .

- On the movement of small particles suspended in a stationary liquid, as required by the molecular kinetic theory of heat , in which he provided empirical evidence of the reality of the atom and gave credence to statistical mechanics , a branch of physics relegated at that time.

- On the electrodynamics of moving bodies , a precursor to his great theory, in which Einstein reconciled Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism and the laws of classical mechanics : he proposed the speed of light as the maximum achievable speed, accessible only to photons.

- Does the inertia of a body depend on its energy content? This is the question from Einstein’s work, in which he deduced the most famous equation of all time, or at least the one most reproduced on t-shirts and mugs. The equivalence between the mass of a body at rest and the energy it can be converted into: E=mc² .

Clock synchronization

Every time someone opens Google Maps or their car’s navigation system, the proper functioning of the GPS depends directly on Einstein’s theory of relativity.

The satellites that make up the GPS system move very fast and are located far from the Earth’s surface, where the Earth’s gravitational influence is weaker. Einstein discovered that time does not advance at the same rate under all circumstances: gravity and the speed of the object modify it. Therefore, the clocks on the satellites tend to run faster or slower than those on the Earth’s surface.

The GPS system corrects for this effect by applying the equations of special and general relativity . Without it, positioning errors of several kilometers would occur within a single day. Similarly, modern internet and telecommunications infrastructure depends on extremely precise synchronization between clocks distributed across the globe, many of them also on satellites.

If these clocks were not corrected in accordance with general relativity, electrical grids, electronic payments, air navigation, and the internet itself would suffer major failures.

Every connection, every video call, and every bank transaction benefits, without us even noticing, from the way Einstein changed our understanding of time and gravity.

Solar panels: a matter of photons

Modern solar panels work thanks to the photoelectric effect, which was explained by Einstein in 1905 – this merit was rewarded with the Nobel Prize in 1921 –.

He proposed that light is made up of packets of energy called photons and that, when a photon with enough energy strikes certain materials, it can knock an electron from their surface. This ejection of electrons is what generates an electric current in a solar cell.

Every domestic photovoltaic panel, every solar street light, and every small portable solar charger is based on exactly the process that this scientist described: light that releases electrons and electrons that generate electricity.

Video calls and digital screens

Digital photography, mobile phone cameras, webcams, and virtually every modern image capture system also work thanks to the same effect. In CCD and CMOS sensors , which have replaced traditional photographic film, each point in the image is a tiny cell that releases electrons when it receives light.

That release is measured electronically and converted into a digital image. The physical principle behind every everyday photo, video, or video call is exactly the one Einstein described in 1905.

Large and small lasers

Lasers, which are now used in a wide variety of applications, work according to a mechanism predicted by Einstein: stimulated emission . In a 1917 article, he theorized that an atom could be “forced” to emit light identical to that which it received, creating an extremely pure, concentrated, and optically coherent beam of light.

Decades later, this prediction became the operating principle of the laser. Today, we find lasers in barcode scanners at the supermarket, optical mice, laser printers, CD players, fiber optic internet connections, and some medical procedures.

Nuclear medicine

Nuclear energy and several modern medical techniques rely on the equation E=mc². This relationship states that a small amount of mass contains an enormous amount of energy.

Understanding this link made it possible to explain the functioning of atomic nuclei and paved the way for nuclear reactors, but also for essential medical uses, such as radiotherapy or PET (positron emission tomography) scans, which allow the diagnosis of diseases by detecting small amounts of radiation from atomic disintegrations.

Although it may not be something that a person uses directly every day, it does profoundly affect public health and the treatment of millions of patients around the globe.

In short, every time someone receives a radiodiagnosis or a treatment based on nuclear physics, checks a route on their GPS or charges their mobile phone with a solar panel, they are somehow taking advantage of one of Albert Einstein’s ideas.

Author Bio: Francisco José Torcal Milla is Full Professor. Department of Applied Physics. Center: EINA at the Institute: I3A, University of Zaragoza