If the history of slavery has given rise to several recent works – whether we think of Beloved by Toni Morrison or Twelve Years a Slave by Steve McQueen, adapted from the testimony of Solomon Northup – it remains a complex subject to approach in the literature for young people.

How, indeed, to introduce children and adolescents to the knowledge, highly necessary, of a period of history known for its atrocities? How can we draw fictions from it, when we also have so few direct testimonies from slaves?

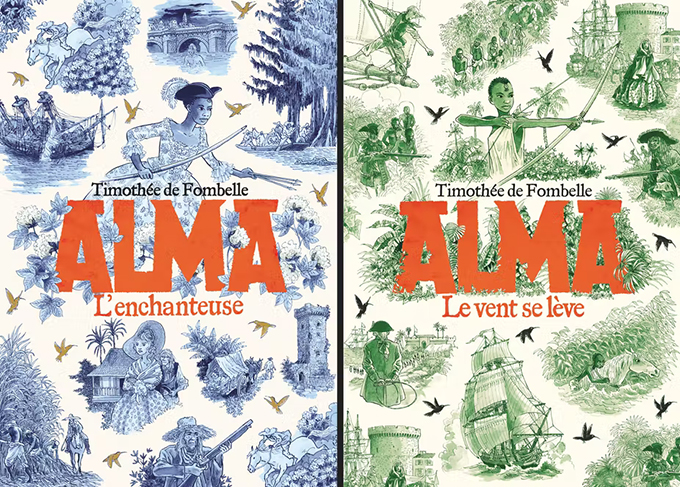

This is the project that Timothée de Fombelle took on with his Alma trilogy , the first two volumes of which, Le Vent se lève and L’Enchanteuse , were published by Gallimard Jeunesse in 2020 and 2021. Born in 1973, Timothée de Fombelle is the author of several success stories for young people, in particular the adventure novels Tobie Lolness (2006-2007) and Vango (2010-2022). Alma draws from the history of the 18th century a plot that addresses the trade of black Africans, deported as slaves by Europeans to American territories.

Invited to the University of Nanterre in the spring of 2022, as part of a series of meetings devoted to the 18th century in contemporary novels, Timothée de Fombelle came to present Alma , to explain his working method (its sources, the place he grants to the documentation…) and talk about the writing work of the novelist confronted with such a subject.

His story intersects the destinies of many characters: captives and sailors, hunters and landowners, against a backdrop of debates for abolition. It all started in 1786, in the Isaya Valley, somewhere in Africa. Alma spends happy days there with her family. When her brother is taken prisoner by slave hunters, the young girl is ready to do anything to find him, even if it means following him to the end of the world.

She will discover the terrible conditions of the Atlantic crossing, the effervescence of Saint-Domingue – a colony which will soon be stirred up by a powerful revolt –, the injustices in the plantations in Louisiana and the suspended splendor of the Versailles court.

In the documentation yard

Writing about the Atlantic slave trade, even to compose a novel, presupposes doing some documentation work beforehand. Not only out of historical fidelity, but because the extent of the suffering experienced commits the writer, to a certain extent, to a requirement for accuracy, where reality sometimes exceeds imagination.

How to represent, in fact, the derisory place granted to captives in ships? Alma , around the rich illustrations of François Place, takes care to evoke with meticulousness the slave ships like the functioning of the plantations. It is important for young readers to understand this triangular trade , the way in which shipowners convert “invisible gold” into human beings, then into goods, and then back into gold.

However, this knowledge, nourished by the reading of numerous documents, should not become encyclopaedic. It is by strictly romantic means that Timothée de Fombelle recounts these lives tossed about on three continents. Alma surprises by the number of its characters, rare in a work for young people.

In addition to the eponymous heroine, we find Joseph Mars, a French ship’s boy, Amélie Bassac, daughter of the shipowner and owner of the plantation – she who “struggles to open her eyes to the immensity of the dramas that live these men and these women” –, Gardel, the infamous captain, or even Oumna, this famous captive Eve, whose memory we try to erase with the name…

This multitude of characters, which appears on the cover of the book, makes it possible to evoke all those who, directly or indirectly, took part in the slave trade and thus to represent it in all its complexity.

An initiatory journey

Alma chooses an omniscient narrator, capable of commenting on the overhanging facts as well as interfering in the thoughts of each other. The exercise is not easy. How can we talk about slavery without speaking on behalf of those who lived through it? A sign of the stakes attached to such an undertaking, the publisher Walter Brooks, who translates most of Timothée de Fombelle’s works, has decided not to publish Alma in English.

Dominated by a deliberately critical narrator, the novel gives access to the successive points of view of captives, more or less involved outside spectators, sometimes slavers. Joseph Mars, the cabin boy to whom the prisoners crammed into the ship are described, repeats: “I know”, but “he knows very well that he doesn’t really know”. He had to watch the long march of the Africans taken in the boat to become aware of this reality.

Young readers are invited to complete the same initiatory journey, in front of the procession of these exiles, as in their eyes “the white edge of their continent” fades away. Means, no doubt, of making these readers feel through fiction, from the end of their imagination, what slavery meant.

It is sometimes necessary to use devious means to represent the worst in a novel for young people. An old pirate tells how a ship full of captives was sunk for a purely administrative reason. The reported speech shows here without showing directly. In the same way, when the young slave Lam runs away, the possibility of failure – of the punishment that awaits him – is formulated in denarred form, in the form of a simple hypothesis: Lam will manage to escape and to join the maroon rebels .). The novel navigates in this way, aware of the two pitfalls of overbidding and watering down.

The wake of the Lights

It is a whole section of the history of the 18th century that Alma shows , but also of its literature. Behind the voice which declares, in Le Vent se lève : “All this misfortune for a little coffee, jam and chocolate at snack time… For this madness of sugar which has invaded the living rooms of Europe”, we hears the great abolitionist texts that continue to nourish the collective memory. “It is at this price that you eat sugar in Europe,” said the mutilated slave in Candide by Voltaire.

Scene from Paul and Virginia”, by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre. Charles-Melchior Descourtis, via Wikimedia

“It will be agreed that no cask of sugar arrives in Europe that is not stained with human blood”, wrote Helvétius in De l’esprit . We also find in Alma , as in Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, the opposition between the utopian micro-space of the happy valley and the big bad world, in which the slave trade has free rein. We believe we are seeing Domingue again, this character from Paul and Virginia represented in famous prints and paintings of the time.

Yes, there are echoes of the Enlightenment in Timothée de Fombelle’s novel, but also a questioning of the latter, in the wake of a historiographical current which insists on their ideological ambiguities. The owner of the slave ship has an impressive library, which does not prevent him from enriching himself with the slave trade. In the property of Santo Domingo that the heroine crosses, we find the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, nibbled by rats – these same rats with which the slaves reduced to eating them poison themselves. Here again, Alma traces her path between celebration and unequivocal criticism.

“It is forbidden to know what has not yet taken place”, declares the narrator mischievously, before embarking on a well-known historical episode – the sinking of the La Pérouse expedition. The second volume of Alma leaves us in 1788, in Versailles. The curious have an idea of what awaits them, in volume 3, from 1789…

In the meantime, young (and less young) readers will have, for two volumes, discovered in all their complexity these “tangled lives” by the slave trade, in a powerful adventure novel which focuses on a few decisive years of our history and which aims to embody its memory.

Author Bio: Audrey Faulot is a Lecturer in 18th century French literature at the University of Paris Nanterre – University of Paris Lumières