At the recent Times Higher Education Teaching Excellence Summit at the University of Glasgow, James Conroy, vice-principal (internationalisation) at Glasgow, found himself in a “robust” exchange with Carl Wieman, Nobel prize-winning physicist and unwavering advocate for the swift dispatch of the lecture as an educational practice.

A couple of hours later, gazing at the magnificent Galloway Memorial Window that adorns the Bute Hall, Professor Conroy picked out some words, or rather invitations, etched into the building’s stained glass. These included the virtues of perseverance and fidelity. In the contemporary argument about effective learning, it would appear that much has been forgotten about the purposes of education – purposes that were present to our forebears.

Wieman’s claim that we should abandon the lecture in favour of “experiential” or “active” learning – a claim based on a plethora of studies and research reviews conducted over recent years – requires a more serious riposte than is available in the rhetorically charged setting of the lecture space.

We are more than content to agree to the desirability, indeed necessity, of a wide range of experiential, innovative and interactive learning opportunities in the modern classroom.

Indeed, it was surprising that Wieman’s examples, used to illustrate the enhanced learning outcomes of “active learning”, included one on series and parallel lighting circuits. Frankly, this was the kind of experiment that we were asked to conduct in a school’s physics lab as 12- to 13-year-olds in the 1960s!

So we are, of course, not suggesting that such “experimental” learning isn’t important or appropriate. However, Wieman’s proposition is a different one: that for every educational objective, the lecture is a demonstrably inadequate method.

A particular conception of “educational research” has emerged in recent times that is obeisant to a particular subset of scientific (often biomedical) models of inquiry, in which empirical studies (often randomised controlled trials) into learning interventions are most prominent and which are, in the UK and US at least, the most regularly funded.

These approaches have been embraced by many governments, intent on securing industrial and commercial advantage in a highly competitive globalised workspace.

They draw heavily, not only on a supposed clinical scientific method, but also on a “religious” dogma going back to John Dewey, Lev Vygotsky and others that “relevance” and “proximity” to what one already knows represent the philosopher’s stone of educational practice. Such adherence to a certain way of thinking about social practice is itself, necessarily, socially constructed and carries a raft of assumptions as to what is of value and what isn’t.

Moreover, even in clinical trials, where RCTs “rule the roost” (effectively critiqued by, among others, Paul Smeyers and David Bridges), there are frequent problems of causality and inference. The very act of isolating a particular intervention or feature of a social practice often misses and/or misunderstands the connected and cumulative nature of such practices – such that a well-trialled medication for condition x may generate adverse side effect y; the patient then has to take an equally well-trialled medication for y, which in turn throws up side effect z. And so the story goes, until one day a GP is prescribing in excess of 20 drugs to a morbidly ill patient.

The corresponding isolation of components of educational practice reflects a misunderstanding of the distinction between two things: performance and learning. As Elizabeth Bjork and Robert Bjork point out, “it is possible to have performance without learning and learning without performance and…conditions of retrieval practice that often facilitate long-term retention frequently may appear unhelpful in the short term compared with their counterpart conditions”.

There is a problem with these methods: that of confirmation bias coming from the extended dominance of a certain view of the superiority of the “experiential” over the ruminative and reflective.

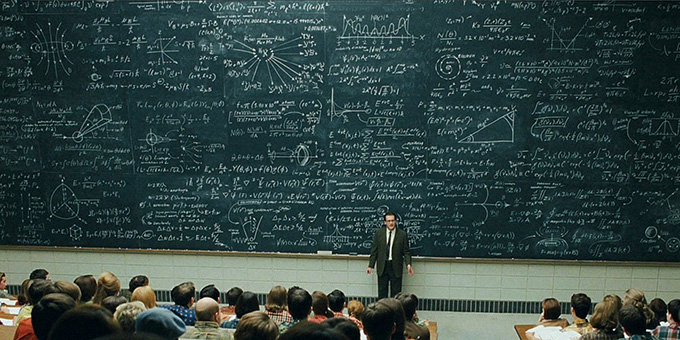

Let us, then, turn to the ruminative and, more broadly, to those purposes of the lecture constitutively resistant to Wieman’s instruments for measuring them. Lectures are unlikely to be the best instruments for work better conducted in a laboratory or workshop. However, such work is by no means the only – or indeed the most important – feature of a university education.

Without succumbing to nostalgia, it is perfectly possible to embrace education as an invitation: an invitation to consider matters entirely outside one’s own existing experience – and the lecture is a critical mode of such invitation. It invites us to slow down. Professor Conroy’s first encounter with the lecture was as a 14-year-old listening to another Nobel laureate, Seamus Heaney, talk about language, culture and identity. Of course, the content may have long dimmed, but the shaping echo of the invitation, the timbre, “the heft and thump of the thing”, remains vitally alive. It is in this regard that the lecture invites us to “slow down”.

The lecture can also be a provocation, a call to think differently; a signposting in lands that, for the student, could be terra incognita. Lectures, then, may also be a call to attention. In a world of hyper-complexity that we now inhabit, fresh attention to a complex argument is part of that same educational invitation.

Wieman’s claim that lectures are in every case a lesser form of instruction misunderstands the nature and purposes of the lecture; confuses and conflates “learning” and “performance”; is empirically unsustainable and unjustifiably imposes the particular experiences of one, albeit manifestly important, domain on to all education.

Author Bios: James C. Conroy is vice-principal (internationalisation) and professor of religious and moral education and Robert A. Davis is professor of religious and cultural education both at the University of Glasgow.