It is necessary to distinguish what is called “children’s books” from those which form a “literature for children and young people”. It will take centuries to pass from the first to the second, and this literature will then continue to change. Let us lay down a few milestones in this complex story, which we will be forgiven for simplifying in this way.

The first texts that are placed in the hands of children are school “tools”, primers , extracts from literary works… This has existed since antiquity. Children are also nourished by an oral literature of mythological tales and fables. The Middle Ages will produce the same kind of texts which will become books, first manuscripts, then printed.

The very first book written for a fifteen-year-old and his younger brother was written between 841 and 843 in Uzès by Dhuoda, Duchess of Septimania, entitled Manuel pour mon fils (translation by Pierre Riché, 1975). This mother wrote this book to make her son a perfect Christian aristocrat: it is a civic and religious education manual. From the 13th century, there are also didactic works written by lay people for their children, and religious books are clearly intended for them: “Hours for a girl” or “for a boy”, and also a “child’s psalter” . .

When does children’s literature appear?

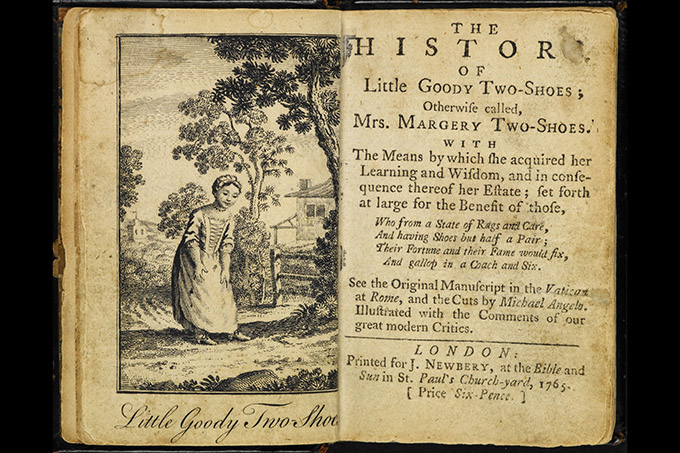

In fiction producing a moral to be inculcated in childhood, the role of Aesop’s fables should be noted. From the 15th century, a text translated into French was printed in small format, with large characters and woodcuts, for a popular readership and a childish public , which was not yet the sole target of these first publishers. Note, however, an incunabula printed in Lyons in 1484 which bears marks of appropriation by a child, who drew and commented on the book.

The Wolf and the Fox, Fables of Aesop, preceded by his life, translated from Latin into French by Brother Julien, from Les Augustins de Lyon, 1484. BNF, Gallica , Supplied by the author

In the 16th and 17th centuries the repertoire of children’s books , school books, religious, moral, fictional books continued to expand until literature for young people appeared.

The birth of this literature took place in France in two stages, at the end of the 17th and mid-18th centuries . We will only mention the first stage, which foreshadows children’s literature about a princely education and literary games in salons, while the second will widely distribute children’s books by increasingly specialized authors. in writing for young audiences.

Two names symbolize the first stage: Fénelon and Perrault. François de Salignac de la Motte Fénelon (1651-1715) published his Treatise on the Education of Girls in 1687 , in which he advised, so that children want to learn to read, to

“tell them entertaining things from a book in their presence […]. Give them a well-bound book, golden even on the edge, with beautiful pictures and well-formed characters. Everything that delights the imagination facilitates study: you must try to choose a book full of short and wonderful stories […]”.

In 1689 he became tutor to the seven-year-old Duke of Burgundy and to his brothers, the six-year-old Duke of Anjou and the three-year-old Duke of Berry, grandsons of Louis XIV. He then wrote for them a literature graduated according to age. For the little ones he produces tales and fables including Voyage dans l’Ile des Plaisirs ( Fables, VIII ), one of the archetypes of tales about gluttony, with an island made of sugar, mountains of compote and rivers of syrup and the sleeper is awakened at night by the earth vomiting “boiling streams of frothy chocolate.”

Then he recounts the lives of philosophers ( Abrégé de la vie des Anciens philosophes ) and he writes imaginary interviews between great men ( Dialogues des Morts ) thus teaching history and morals, and he ends with the first novel for teenagers of our literature, the Adventures of Telemachus (1699). He chose fiction to seduce his pupil with gentleness, thus circumventing the proud and irascible character of the Duke of Burgundy. If the Télémaque had a considerable bookstore success, it remains that this construction of a literature for children and adolescents is at the beginning located in a princely, private education.

Charles Perrault inscribes his Contes de ma Mère l’Oye (1697) in a literary salon game, for adults, as Madame d’Aulnoy does in her collections of 1697 and 1698. However, these two authors officially display the desire to touch a childish audience . Perrault, in his 1695 preface, advises parents to wrap solid truths “in agreeable narratives proportionate to the weakness of their age”. He shows that he has carefully observed the reactions of child audiences.

As for Madame d’Aulnoy, to put herself within the reach of children, she uses a style that has often been described as silly and childish. But the tales of Perrault and those of Madame d’Aulnoy have effectively become part of the literary heritage for children.

Who are the first publishers for children?

From the middle of the 18th century, books were truly written for children by authors and bookseller-publishers in the process of specializing . It is a question of offering children fictions which are their literature and, for this, children’s characters are staged by new authors: Madame Leprince de Beaumont, Madame d’Épinay, Madame de Genlis , Arnauld Berquin .

In fifty years, great progress has been made in the quality of observation of children, in reflections on their psychology and on education. This leads to an editorial fever to publish an abundance of children’s books, as noted in 1787, at the Leipzig fair, a German teacher, LF Gedike.

But this is not enough to create large specialized publishers. For this, we have to wait for the first third of the 19th century, with two publishers specializing in children’s books, and who are also authors, Pierre Blanchard (1772-1856) and Alexis Blaise Eymery (1774-1854) . However, their economic and industrial base is still quite weak and it is only a little later that major publishers are making their mark on the children’s book market.

While a new literature for young people was being invented in the 1830s, the Guizot law of June 28, 1833 increased schooling and therefore child readership. To this increased demand for children’s books, there is first of all an “industrial” response, which is primarily due to Catholic provincial publishers, some of whom already existed in the Ancien Régime (Barbou in Limoges, Mame in Tours, Lefort in Lille, Mégard in Rouen, Périsse in Lyon, Aubanel in Avignon, Douladoure in Toulouse) or appeared in the first third of the 19th century ( Ardant in Limoges, in 1804, Lehuby in Paris succeeding Blanchard in 1833)

These houses create Libraries for young people, they occupy thousands of workers, equip themselves with modern machines and concentrate all the tasks – printing, binding, illustration. Mame had, in 1855, 1,500 workers and he bound 10 to 15,000 volumes a day. Megard produced six million volumes during the Second Empire, while Mame produced as many per year. In 1862 six provincial publishers, Megard, Barbou, Ardant, Périsse, Mame and Lefort, published nearly ten million volumes. The Parisian houses do not have such productions, but they are more innovative in the field of literary quality and the collections created.

Louis Hachette created the periodical La Semaine des Enfants in 1857 and the Bibliothèque rose illustrée in 1858. Hetzel published the first issue of the Magasin d’éducation et de récréation in 1864. The big names in children’s literature published in Paris, the Comtesse de Ségur at Hachette, Jules Verne at Hetzel, and many more. This distortion between the provincial publishing world and that of Paris is accompanied by debates on what a children’s book should be.

Were these early children’s books intended to entertain or educate children?

Debates about children’s books depend on ideological positions and different visions of childhood. For Catholic publishers, it is a question of forming young people in Christian values according to a vision of a passive childhood and youth that must be saved by forming them through teaching and through readings approved by the episcopate. .

Pierre Jules Hetzel proclaims his contempt for this kind of industrial literature, with authors paid by the quantity of books, and works that he considers to be “without taste or perfume, these flat and flat books, these stupid books, I want say the word, to whom the undeserved privilege seems reserved of being the first to speak to what is finest, most subtle and most delicate in the world, to the imagination and to the hearts of children” (Preface to Louis Ratisbonne , The Children’s Comedy , Hetzel, 1860).

In his Stahl Albums , Hetzel depicts small children illustrated by Frölich’s drawings full of tenderness, and, moreover, by publishing Jules Verne, he offers teenagers the scent of adventure and exotic territories. For its part, Hachette, by publishing the Countess of Ségur does not give a representation of always good and pious children, and it even goes so far as to offer its young readers terrible children, those whose exploits Trim tells us about with the illustrations by Bertall, in albums for three to six year olds. Thus we begin to be interested in the youngest .

And we go so far as to design books for “babies” for which a dedicated offer widens in the 1860s, knowing that the term borrowed from the English “Baby” concerns small children, not infants. We observe attempts at periodicals for Babies between 1862 and 1878, and the publisher Théodore Lefevre, who writes under the pseudonym of Madame Doudet, publishes a “Bibliothèque de Bébé”, with twenty titles between 1871 and 1900, which is addressed to children aged four to eight. We also begin to use the expression of books “for toddlers”, which will become the majority after the First World War. But it was only in the second half of the 20th century that “real” babies were entitled to their books.

Author Bio: Michael Manson is an Historian, Emeritus Professor of Education at Sorbonne Paris Nord University