Yesterday the shadow education minister, Tanya Plibersek, announcedLabor plans to invest an additional A$174 million in the higher education sector if there’s a change of government at the next election. This extra funding would be to give first in family students, students from outer suburbs and the country, Indigenous students, and students with a disability a better chance to study at university.

This is on top of a promise to uncap student places at university. Labor estimates this will see the number of Australians getting a university education rise by 200,000 over 12 years.

But university may not be the best option for everyone. Concern about a glut of students graduating from degrees such as law or journalism and not getting jobs have ignited discussion about whether we should control the number of students entering university or particular courses.

But if universities are to enrol fewer people, we should offer attractive alternatives to university education. To fix higher education, we also need to fix vocational education to help get students into courses with employment opportunities.

Balancing graduates and the labour market

From 2009 until last December, universities could enrol unlimited numbers of bachelor degree students and be paid for each one. This is a system called demand driven funding. It ended when the Commonwealth government announced it would only pay universities a fixed sum of money from 2018 onwards, capping this sum for two years at the amount paid out in 2017.

A major criticism of the demand driven system was that it flooded the labour market with graduates who couldn’t find jobs in their field. In 2014, short-term graduate employment outcomes were the worst on record. Nearly a third of graduates who were looking for full-time work couldn’t find it.

The recent poor employment results for new graduates were partly due to bad timing. Most graduates aim for the professional jobs most likely to use their skills. But growth in the number of professional jobs nearly stalled in 2013 as the mining boom ended and graduations started increasing due to the introduction of the demand driven system. When the economy is weak, new job seekers suffer the most.

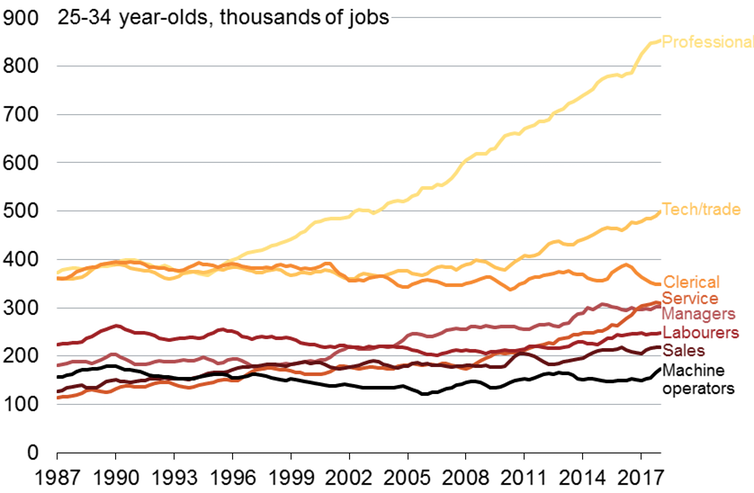

But over the longer run, ABS data shows the number of people in their early career securing professional jobs is increasing significantly. The end of the mining boom paused growth, but it didn’t reverse the long-term upward trend.

Occupational trends, 1987-2017. ABS

No higher education system can produce a perfect balance between graduates and the labour market. Education and the economy will always work on different timelines. But we need a tertiary education funding system that will help get students into courses with employment opportunities.

Fixed funding

Before demand driven funding, with universities getting fixed annual grants as they do again now, the system did not respond well to the labour market. In 2008, 40 professional occupations were in skills shortage, with health-related fields such as aged care particularly badly affected. If Australia hadn’t been able to import large numbers of health professionals from overseas, this would have been a public health disaster.

Capped funding for universities makes it hard for them to respond to workforce issues as they emerge. Universities aren’t funded to accommodate the number of students who want to study or the number of skilled graduates needed in key areas, such as health care.

The demand driven system mostly responded to labour market signals…

Under demand driven funding, the higher education system adjusted to demand for graduates in certain fields and oversupply in others without government intervention. Demand driven funding does not mean endless, rapid growth in the numbers of students studying at university.

We can see how labour market information flowed through to student behaviour. Media reports highlighting poor graduate outcomes likely played a role in communicating market signals to students.

As reports in NSW spread of teaching graduates not finding work, the number of students commencing teaching degrees in NSW fell by nearly 2,000. The number of people accepting an offer for an engineering course also fell as the mining boom ended. A shortage of skilled health workers was the biggest problem under the previous system, and health-related enrolments grew by the most under demand-driven funding.

By 2015 the enrolment boom that began in 2009 was over. Only five professional occupations remain in skills shortage, including surveyors and vets.

But not always

Students don’t always react to bad labour market news. Science added more than 12,000 commencing students between 2008 and 2016, as employment outcomes went from mediocre to terrible.

The Chief Scientist and politicians promoted science, which may have misled students. The science experience is a reminder to policymakers they need to be careful about the signals they send to students.

Offer attractive alternatives to university

Although well-motivated by concerns about who has access to a university education, Labor’s current talking up of higher education may not be good advice to students in every case. The demand driven system has often responded to labour market signals, but some further moderation in the numbers of students attending university would make it easier for graduates to find professional jobs.

But if universities are to enrol fewer people, we should offer attractive alternatives to university education, rather than simply restricting university student numbers. Vocational education is one of those potential alternatives. Technical and trade employment is also growing, as the chart above shows. Thirty technical and trade occupations were in skills shortage in 2017.

Unfortunately, university demand driven funding coincided with chaos in vocational education, thanks to state governments cutting funding for vocational education and the VET FEE-HELP fiasco.

It’s hard for VET to compete with university when it’s underfunded. Julian Smith/AAP

It’s hard for vocational education to compete with universities when students sometimes need to pay thousands of dollars out of pocket for their course, while higher education undergraduates can defer all their tuition costs via HELP. The student income support system is also biased against vocational education, with restricted eligibility and lower payments.

The policy status quo of capped higher education funding and a funding bias against vocational education will not serve us well. With restored demand driven funding and changes to vocational education, the tertiary education system would do a better job of matching students with the courses that maximise their long-term employment outcomes.

Author Bio: Andrew Norton is the Higher Education Program Director at the Grattan Institute