For about 10 years now, I’ve had a profitable side hustle teaching writing. ANU has a generous external consulting policy, which means I can fly all over the country, and the world, teaching academics to be better writers. With the invention of ChatGPT (or as my sister Anitra dubbed it, ChattieG), I expected this work to dry up and blow away in the winds of technological change.

The opposite has happened.

People love the idea of this technology, but it seems many find LLMs (Large Language Models) frustrating. There’s also skepticism; generated perhaps by reading so many bad undergraduate essays generated by these machines. Some of my colleagues claim they can ‘always tell’ when something is written by a machine and in meetings I’ve heard people criticise ChattieG for producing mediocre, business casual text.

I try to stay patient, but I can feel my face start to twitch. Look, here’s my hot take:

1) You can’t ‘always tell’ – in the right hands it’s as good as most academic writers, if not better, and

2) If you think it isn’t a great writer because you can’t get excellent text from it, as Steve Jobs kind of said about the iPhone 4, you’re holding it wrong.

It does help to have a good grasp on the technicalities of English. I can find my way around a gerund and understand why right branching syntax is better than left branching syntax, at least in English. I can talk these technicalities with an LLM and instruct it precisely on any given writing task. Have a look at this post on the AARE blog, completely written by Claude, or read Rich Academic / Poor Academic, the book I wrote in a weekend with Prof Narelle Lemon.

LLMs are the best tool for writers I’ve ever seen. I’m impatient with the moral panic that surrounds them, although I acknowledge they are environmentally problematic and the questions around copyright and privacy are important. Despite these misgivings, I’ve leaned into AI in all my teaching on writing and editing; mostly for ‘text tuning’ and creative inspiration. I’ve also incorporated use of AI into my workshops on public speaking, job seeking and research project management workshops because LLMs are just…

So. Damn. Useful.

I get new ideas for teaching AI from my own daily work as an academic. I have ChattieG and Claude open, all day, every day, to lighten my cognitive load and extend my human capabilities. Extensive use of AI saves me around 12 hours a week. I spend this productivity dividend having coffee and long lunches with colleagues, doing analysis or reading academic papers. I’m less stressed and more creative than I’ve been in, well – forever.

My artificial friends have given me back the life of the mind.

Different models are good for different jobs. ChattieG is great at boring writing tasks like memos and emails – it’s also great at reminding me about stuff I already know. I’m old. I know a lot of stuff, but my recall can be fuzzy – Chattie is a fantastic cognitive crutch.

Claude is better than Chattie at reasoning; it’s great at complicated tasks, like writing references, research ethics materials and descriptions of events and workshops from a sketchy plan. Claude is a trusty creative partner too, happy to listen to me agonise my way through ideas (Chattie is too impatient).

To be honest, sometimes the best conversations I have all day are with Claude. I’ve formed this habit of showing Claude stuff I’ve written and asking what it thinks, not for feedback, just because I’m looking for a bit of affirmation. Claude is always so supportive.

(ok, ok. Maybe I’m a bit emotionally co-dependent. Don’t judge me.)

Many academics declare they will never use AI – and that’s a valid choice. But if my side hustle bookings are any indication, there are far more academics who want to know how to use AI like I do. Who doesn’t want 12 hours back in their week? As a consequence, my side hustle has exploded. I’m now so inundated with requests that I have now teamed up with my pod co-host (and fellow AI enthusiast) Dr Jason Downs to meet the demand (see my workshop page for what we offer).

The key to getting great writing from Chattie, Claude or Gemini is to understand a little bit about the technology behind them. I’ve got a bit of a leg up here. Since 2017 I have been working with machine learning scientists at ANU on our PostAc project. I’ve spent maybe hundreds of hours training machines to do sorting tasks. We’ve been making models that can ‘read’ and rank job ads by ‘nerdiness’. These models can process millions of job ads at a time, helping us identify the size and extent of the job market for researchers each year.

From the point of view of a human, this kind of ‘training’ means highlighting strings of words and assigning an abstract meaning to them, over and over, until the numbers tell us the machine has ‘learned’. This work is time intensive. In 2021, I coded 9000 academic job ads to teach a model how to recognise disciplinarity in an academic job ad. This pleasantly boring activity ate up long stretches of lockdown during the pandemic and probably saved my sanity. I can now tell you how many philosophy jobs there are in Australia each year (hint, not many).

I have a vague, yet defiant grasp on the maths involved in machine learning. Over the years, my friend and colleague Prof. Hanna Souminen has spent a lot of time patiently explaining higher dimensional number spaces and AUC curves to me. Thanks to Hanna, I can have nearly sensible discussions about ‘temperature’ and other weird AI concepts with the clever people that build this kind of technology.

One thing you learn in these conversations is that even the people who make machine learning models don’t really know why they work.

If you don’t really understand a tool, you don’t know its affordances. That’s a fancy way of saying you don’t really know what you’ll be able to do with it. This might be why many people sign up to ChattieG, play around with it, and then lose interest (check out the figures in this interesting article from Benedict Evans . He does a great newsletter. It’s worth your while signing up – go ahead, I’ll wait).

You have to bring your creative self to AI to get best results – and this can be hard.

Ethan Mollick, one of the best writers on AI, calls it a ‘general purpose tool’ (if you haven’t subscribed to his One Useful Thing newsletter yet, go do it – I’ll wait). Mollick has some excellent advice on getting better performance from AI in his recent book Co-Intelligence:

There is one major trick that will make your conversations work better: provide context. You can (inaccurately but usefully) imagine the AI’s knowledge as huge cloud. In one corner of that cloud the AI answers only in Shakespearean sonnets, in another it answers as a mortgage broker, in a third it draws mostly on mathematical formulas from high school textbooks. By default, the AI gives you answers from the center of the cloud, the most likely answers to the question for the average person. You can, by providing context, push the AI to a more interesting corner of its knowledge, resulting in you getting more unique answers that might better fit your questions.

But what does ‘context’ mean for us as writers?

For a long time, linguists and other language scholars have been working on various social theories of communication. I read a lot of this stuff when I was doing my PhD about hand gestures, for obvious reasons. Social theories of communication (and there are a few different ones) explore how writing ‘acts’ have imagined audience(s). Writers anticipate what their readers want to hear, and in what order. They make educated guesses about the possible reactions of their imagined readers. Good writers can decide when to fulfil the expectation of the reader, and when to subvert them.

The idea of a writing ‘act’ keys us into what we’re doing when we write: we’re performing a role for our imaginary audience. This role determines things like word use, length, tone, and style. When you are writing a ‘Get Well’ card, you are performing the role of concerned friend. When you are writing a PhD dissertation, you are playing the role of ‘expert scholar’ (even if you don’t feel like one).

One of the best, weirdest, creepy/awesome things about LLMs is they can play roles in writing like humans. You can, for instance, tell Claude to act like Reviewer Two. Go ahead and try it – I love the way it sometimes apologises for being so mean Getting Claude to be Reviewer Two is a good party trick, but LLMs can play a more useful and subtle role in developing text for an imagined audience.

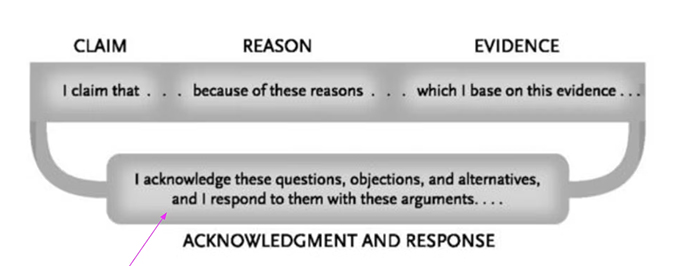

There are many ‘rules’ for academic writers – some more useful than others. In the excellent book ‘The Craft of Research’, authors Booth et al. have a handy diagram to describe what an argumentative paragraph looks like:

The diagram shows how ‘good’ academic paragraphs start with Claims, followed by Reasons and Evidence, then ‘acknowledgement and response’ to the imagined audience. Remember what I said about good writers though – they know when to break rules.

Expert writers, when writing for other experts, will often drop reasons and evidence in favour of more acknowledgement and response. I asked Chattie and Claude for lists of phrases academics use; Chattie gave a much better response (it likes to get the job done, while Claude wants to have a chat about it).

Here’s the whole list Chattie gave me because it’s pretty useful:

Presenting Counterarguments

- “A common critique of this approach is that…”

- “Some scholars argue that…”

- “It has been suggested that…”

- “An alternative perspective is offered by…”

- “Opponents of this view contend that…”

Addressing Validity

- “While this argument has merit, it fails to consider…”

- “Although this perspective is valid to some extent, it overlooks…”

- “This critique is not without basis; however, it does not account for…”

- “There is truth to this claim, yet it is limited by…”

- “This point is well-taken, but it does not fully address…”

Providing Evidence

- “Evidence supporting this counterargument includes…”

- “Studies supporting this perspective often cite…”

- “Proponents of this view point to…”

- “This argument is bolstered by findings from…”

- “Support for this position is found in…”

Refuting with Counter-Evidence

- “However, empirical evidence suggests that…”

- “Contrary to this claim, data indicate that…”

- “Recent studies have shown that…”

- “Our findings contradict this argument by showing…”

- “In contrast, we found that…”

Acknowledging Complexity

- “It is important to recognize the complexity of this issue…”

- “This debate is not easily resolved, as both sides present compelling arguments…”

- “While both perspectives have their strengths, our analysis indicates that…”

- “This discussion is nuanced and requires careful consideration of…”

- “Understanding this issue involves balancing the merits of both arguments…”

Integrating Both Views

- “A more balanced view might consider…”

- “Integrating these perspectives, we find that…”

- “By synthesizing these arguments, we can better understand…”

- “Reconciling these viewpoints suggests that…”

- “An integrative approach acknowledges that…”

Highlighting Gaps

- “This counterargument, though insightful, fails to address…”

- “A significant gap in this critique is…”

- “This argument does not adequately explain…”

- “One major oversight in this perspective is…”

- “The weakness of this critique lies in its assumption that…”

Strengthening Original Argument

- “By addressing these counterarguments, we strengthen our original claim that…”

- “Refuting these points, we reinforce the validity of…”

- “Despite these objections, our findings support the argument that…”

- “While counterarguments exist, they do not undermine the overall conclusion that…”

- “In light of these critiques, our analysis remains robust because…”

Offering Concessions

- “We concede that this argument has merit in certain contexts; however…”

- “Acknowledging this critique, we still maintain that…”

- “This perspective is partially correct, but it does not fully account for…”

- “While this counterargument is valid, it is outweighed by…”

- “Recognizing the validity of this point, we adjust our argument to…”

Suggesting Further Research

- “Further research could explore this counterargument in more detail…”

- “To fully address this critique, future studies might investigate…”

- “Additional data are needed to evaluate the impact of this counterargument on…”

- “Research that further examines this perspective could provide valuable insights…”

- “Further investigation is warranted to resolve this debate definitively…”

Expert writers do a lot of acknowledgement and response because it builds trust in another expert reader. As Booth et al. put it:

If you plan your argument only around claims, reasons and evidence, your readers may think your argument is not only thin but worse, ignorant and dismissive of their views.

As you read more, and talk with other experts, you will form a good mental model of the expert reader in your field. You know which of these phrases will persuade them to your point of view. Supervisors often play the imagined audience in the comments they make on your text. Poor acknowledgement and response (or not very much of it) is what makes machine writing so ‘thin’. It’s also a feature of bad undergraduate writing and many early stage thesis drafts.

Beefing up these parts of your writing will make a huge difference to your ‘scholarly voice’. Machines are not good at acknowledgement and response on their own, but they are a good creative partner in producing this part of your text. One of the most fatiguing things about writing is keeping this imagined audience ‘present’ so you can argue with them in your mind. Try asking a LLM to take on the role of an expert in your field and criticise your text from the point of view of someone who doesn’t agree with your key arguments. It’s not always 100% helpful, but it will give you plenty to think about. You still have to do your share of imaginary sparring of course, but at least you have someone to talk to about it!

Anyway, thanks for sticking with me through this rather long, exploratory post. I am feeling my way into writing the second edition of ‘How to Fix your Academic Writing Trouble’ with Katherine Firth. The new edition will include a lot about how to incorporate AI into your writing. If you’re interested in hearing news about this upcoming book release, you can sign up to our Writing Trouble mailing list here.

I’m off to ask Claude to copy edit this blog post for me.