Let’s pause for a moment and observe the gentle flow of these words before our eyes, that silent back and forth, and the voice reading them in our heads. How many of them will stay with you five minutes from now? And how many will effortlessly lodge themselves in our memory tomorrow? The question isn’t trivial. We live in an age where speed dominates our way of learning and, paradoxically, also of forgetting.

Not all words are processed at the same rate. You may have heard that a person can read between 200 and 300 words per minute, listen to around 150, or touch-read Braille at even lower rates. But that speed doesn’t equate to comprehension: in fact, beyond 500 words per minute, assimilation plummets dramatically. And what is absorbed, is it really retained? Not necessarily. Devouring words greedily is not the same as nourishing oneself with their essence.

Different memories in one

For words to make sense and transform into lasting ideas or concepts, they must first pass through the fragile and ephemeral space of working memory—also known as short-term memory— which is responsible for keeping information active while the brain processes it. But that’s not enough.

For what is retained to be stabilized, information needs to be stored in a type of semantic, affective, spatial, or temporal memory . Remembering a vacation involves episodic memory, tinged with emotion and place; in contrast, knowing that Rome is the capital of Italy refers to semantic memory , devoid of personal context.

By hand or by keystroke?

It’s hard to find a space these days where the keyboard hasn’t almost completely displaced ink or graphite. However, it’s worth remembering that handwriting remains a powerful tool for cognitive development : writing manually activates a broader network of brain regions—motor, sensory, affective, and cognitive—than typing. The latter, being more efficient in speed, requires fewer neural resources and favors passive engagement of working memory.

In contrast, the active use of working memory (using analog tools) is more beneficial both in the classroom and in clinical contexts related to cognitive

Pauses are sacred

Rhythm and pause are also crucial in this transition from working memory to long-term memory. Active breaks—brief moments in which we interrupt our study to stretch, walk, or contemplate something with no immediate purpose— allow the brain to reorganize what we’ve learned and consolidate it more firmly.

However, today, these breaks are often combined with activities that involve the use of screens: cell phones, television, tablets. If we could draw a comparison with physical exercise, we could imagine ourselves in a gym where we run at 12 km/h during breaks between sets. Something very similar happens when we use breaks to watch quick videos, read headlines, or scroll aimlessly on social media: the mind doesn’t rest, it doesn’t consolidate, and attention becomes fragmented.

Work during sleep

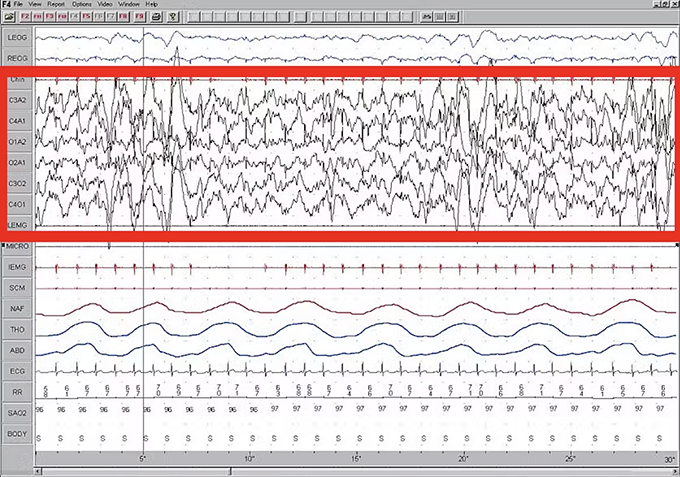

Neuroscience also emphasizes the crucial role of sleep in memory consolidation. During slow-wave sleep , the brain enters a state of neuronal synchronization characterized by the predominance of delta waves (0.5–4 Hz), which favor the reactivation of memory traces —imprints left in the mind after an experience, which serve as the basis for memory and the possibility of recall.

These slow oscillations create a low-interference sensory environment that facilitates communication between the hippocampus and the neocortex . In particular, theta waves (4–8 Hz), which are more frequent during REM ( Rapid Eye Movement ) and also present in light NREM ( Non-Rapid Eye Movement ) sleep, have been observed to mediate this transfer. Specifically, they allow memories to pass from temporary storage in the hippocampus to long-term storage regions of the cortical brain .

Slow-wave sleep in an electroencephalogram. Wikimedia Commons. , CC BY

Similarly, sleep spindles —brief patterns of brain activity that occur during light sleep, generated primarily by the thalamus— are associated with the strengthening of relevant neural connections.

Various studies using polysomnography and neuroimaging have shown correlations between the density of these spindles and performance on episodic memory tasks. It has been proposed that these oscillations act as a kind of “salience marker” that selects which information deserves consolidation.

Thus, while we sleep, the brain automatically carries out a process of reorganizing and reinforcing memory. It prioritizes what is meaningful and eliminates what is irrelevant. It is no coincidence that, upon waking, a seemingly trivial melody or phrase effortlessly returns to consciousness: they are the echo of that meticulous night’s work in which memory is written.

Regain good habits

Understanding how we learn also reveals how we should live. It’s not just about reducing screen time, but also about recovering a more human rhythm. Writing by hand helps activate deep neural networks; think, for example, of class notes and how, when rereading them, ideas resurface more clearly.

On the other hand, it’s advisable to get back into the habit of taking real breaks, away from devices: watching a bird fly by, feeling your breath, stretching your body.

It is also useful to reinforce what you have learned through short active recall exercises —for example, explaining aloud a passage you read an hour ago.

Furthermore, we shouldn’t underestimate the role of deep sleep: it’s where memory matures and consolidates what we’ve learned. Only when we give it the time it needs to rest and process does knowledge truly take root. Thus, the words you read today can become living memories, capable of staying with you beyond the next five minutes, perhaps for a lifetime.

Author Bio: Maria del Valle Varo Garcia is Research assistant professor at the University of Deusto