When ChatGPT launched a year ago, headlines flooded the internet about fears of student cheating. A pair of essays in The Atlantic decried “the end of high-school English” and the death of the college essay.“ NPR informed readers that ”everybody is cheating.“

Meanwhile, Teen Vogue ventured that the moral panic ”may be overblown.“

The more measured tone in Teen Vogue tracks better with preliminary findings from our 2023 survey that examined attitudes and feelings about artificial intelligence among college faculty who teach writing. Survey responses revealed that AI-related anxieties among educators around the country are more complex and nuanced than claims insisting that AI is outright and always bad.

While some educators do worry about students cheating, they also have another fear in common: AI’s potential to take over human jobs. And as far as teaching, many educators also see the bright side. They say they actually enjoy using the revolutionary technology to enhance what they do.

The survey

Our 64-item survey included a scale of AI anxiety and was conducted March 2-31, 2023. The 99 survey respondents included faculty, writing program administrators and others interested in the teaching of writing. More than 71% worked in the disciplines of English, writing or rhetoric, and the sample represented all types of institutions, from small liberal arts colleges to large research universities and everything in between.

A complex picture of cheating concerns

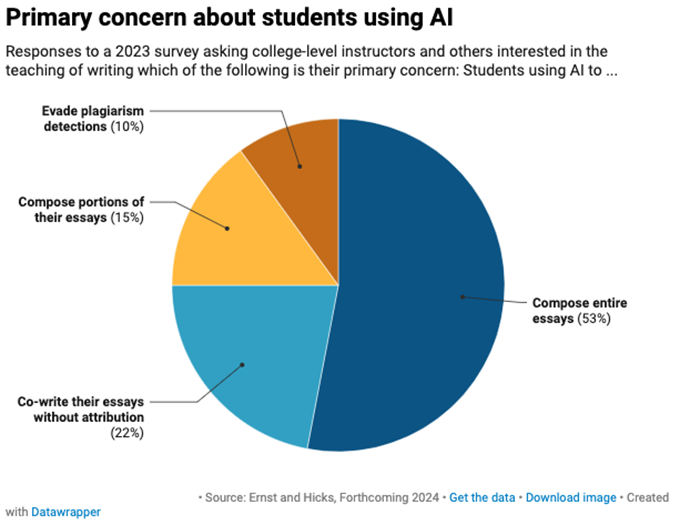

AI anxiety among writing instructors is complicated. While 89% of survey participants feared “misuse” by students, misuse means different things to different people. Specifically, less than half of respondents – 44% – were “concerned” or “very concerned” about students turning to AI to compose entire essays. Only 22% were “very concerned” about students relying on such technologies to “co-write” their essays without providing appropriate attribution.

Additionally, less than half – 42% – reported they were “concerned” or “very concerned” about the need to revise university honor codes and plagiarism policies in light of AI. And only 25% said their institutions should enforce increased plagiarism detection through apps and websites such as Turnitin.

Regardless of whether respondents had deep worries or mild concerns, only 13% favored any ban on AI entirely in college courses and classrooms. Instead, instructors reported varying levels of anxieties about a range of issues, including learning how to use AI tools and job security.

As one participant wrote, “While I want students to compose original works in my writing courses, I see no reason to ban them from using AI tools at their disposal during the writing process.”

Fears beyond cheating

Survey participants had wide-ranging reactions to the prospects of AI replacing their jobs as writing instructors. At times, their feelings seemed conflicted, depending on the circumstances and conditions described in our survey questions.

As some critics have already suggested, there is genuine fear about colleges using AI not as a means to enhance the work of instructors, but instead to replace them.

For instance, more than 54% of respondents “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the prospect of AI technology replacing human jobs scared them. And 43% “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that they were anxious over the possibility of becoming unable to keep up with advances in AI techniques and products.

The anxiety among tenured and tenure-track faculty was significantly lower than that of adjunct instructors, graduate teaching assistants, instructors and administrative faculty and staff. This implies that college writing instructors who are most likely to fear losing their jobs because of AI are those who are most vulnerable anyway.

The potential for using AI in writing instruction

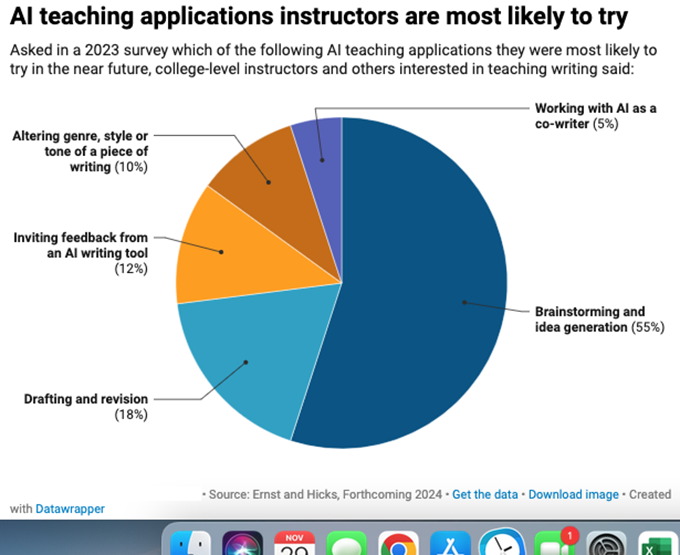

Despite their worries, many respondents reported being eager to use AI writing tools with their students. About 47% said they would “very likely” teach their students how to use AI in brainstorming and idea generation. In fact, some respondents fully embraced the technology as a teaching tool.

“I’m not anxious about AI,” wrote one respondent. “When the computer first entered the writing classroom, there was a fear that it would change writing instruction, which it did. We needed to figure out how to help students use the affordances computers offered. Now, few people would suggest teaching writing without a computer.”

Our survey results suggest that writing instructors see the potential for AI to do much more than write a paper for a student. Sixty-one percent said they were “likely” or “very likely” to use AI in drafting and revision, and 63% were “likely” or “very likely” to use AI to show students how to alter genre, style or tone in their writing.

To be sure, 46% “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that teachers and students could grow dependent on AI. But only 20% “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that their own use of AI as a teaching tool would make students become dependent and cause their reasoning skills to deteriorate.

Now that ChatGPT has been available to students for a year, even the headlines in the news are beginning to reflect the opportunities it can offer in the classroom, in addition to the risks. The Washington Post highlighted “all the unexpected ways ChatGPT is infiltrating students’ lives” – including checking for grammar mistakes. The Wall Street Journal spoke to teachers who said they should encourage students to learn how to use the tool for its potential in their future jobs. And Time magazine reported on the extra hand that ChatGPT gives to busy teachers who are continuously making lesson plans. Clearly, students – and teachers – are using AI. The question now is how, why and for what purposes?

Author Bios: Daniel Ernst is an Assistant Professor of English at Texas Woman’s University and Troy Hicks is a Professor of English and Education at Central Michigan University