Since the Trump administration began slashing the budgets of its main scientific agencies, some university administrators in Quebec—and also in Canada—have found themselves daydreaming aloud: why not take advantage of this “crisis” to attract the “best minds” from the United States, now established as a “bulwark against authoritarian excesses” ?

These sweeping statements, however, make it appear as if researchers and university professors operate in a homogeneous job market. In doing so, they attribute to Quebec universities the magical power to attract scientists who, however, work within institutions with material and human resources that are incomparable to their own.

A deeply hierarchical market

Both professors of the history of science, respectively at the University of Quebec in Trois-Rivières and the University of Quebec in Montreal, our work has focused for several years on the transformations of scientific research.

It therefore seems appropriate to recall that all sociological studies which examine the dynamics of university employment, whether in the United States , Canada or China , arrive at the same conclusion: these markets are very highly hierarchical and unequal.

Their structures are in reality largely determined by the symbolic capital (perceived prestige) of the universities which produce future professors, but also by that of the universities which hire them.

This is without taking into account the linguistic abilities of researchers who – let us remember – must also teach, even if this seems to count for little in the discourse obsessed with “world-class research”.

The case of social sciences

In a recent study , we were able to verify for ourselves the extent of the stratification of the university job market in Quebec, by analyzing the case of social science disciplines (mainly economics, geography, psychology, political science, sociology, communications and social work).

The originality of the Quebec case compared to other linguistically homogeneous markets lies in the fact that two other factors are added to the prestige variable: the language of instruction used by the hiring university and its geographical location.

In this context, the two largest English-speaking universities in Quebec, McGill and Concordia, have a much better chance of recruiting from major American and British universities than their French-speaking counterparts, which are obviously limited in their hiring choices by the language barrier.

To give an overview of the stratification at work, between 1990 and 2020 , the percentages of international hires (i.e. professors who obtained their doctorate outside Canada) are as follows: 53.2% in English-speaking universities, 34% in metropolitan French-speaking universities (Université de Montréal, UQAM and Université Laval) and 12.5% in regional French-speaking universities (UQ network in the regions and Université de Sherbrooke).

Hiring hierarchies in the social sciences

These international hires are themselves very highly hierarchical.

Take the example of top-ranked international universities (regularly ranked among the top 100 universities in the Times Higher Education ranking ), including Harvard, Stanford, Princeton, Cornell, and Berkeley. Graduates from these institutions who come to Quebec mostly find employment at McGill, an institution they consider prestigious and strongly integrated into the American academic field. It is also the only Canadian institution, along with the University of Toronto, to be a member of the American Association of Universities, perhaps contributing to the idea that Canada is… the 51st state of the United States!

Overall, international recruitment by Quebec universities follows a similar logic: whether they are French-speaking or English-speaking, located in large cities or in the regions, they hire professors internationally who are generally trained in universities of a similar or slightly higher rank than their own.

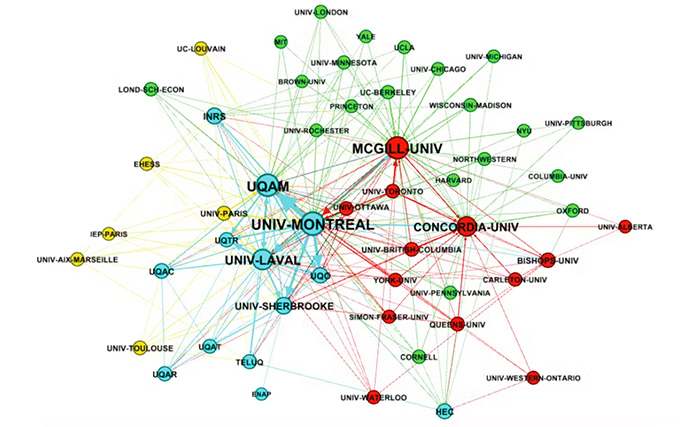

For example, the University of Montreal, Laval University and UQAM mainly recruit internationally doctors trained in the various Parisian universities (Paris 1, Paris 8, EHESS, etc.), or in other major French university cities, as shown in the following figure.

Figure 1: Hiring network of Quebec universities in the social sciences, 1990-2020. erudit.org/fr/revues/rs/2024-v65-n1-rs09576/1113757ar

Similar hierarchies are observed for internal recruitment in Quebec. To give just one example, the chances of a Quebec university located in a large city hiring a professor who obtained their doctorate from a university located in a rural area are almost zero. Between 1990 and 2020 , such profiles represented only 0.4% of hirings in the social sciences at Université Laval, Université de Montréal and UQAM.

The case of natural sciences

One might think that some leaders, transformed into “headhunters”, are only targeting, without saying so, “star researchers” active in the “real” sciences, biomedical and natural.

For another study in preparation, we have therefore compiled data relating to the hiring of professors in these disciplines (anatomy, biology, biochemistry, chemistry, physics, computer science, earth and atmospheric sciences, forest sciences, agricultural and food sciences) since the beginning of the 21st century .

Between 2000 and 2024, of the 1,545 professors hired by the natural sciences departments of Quebec universities, 702 (or 45.4% of the total) obtained their doctoral degree outside Canada, including 261 (or 16.9% of the total) in the United States.

However, of these 261 professors, 167 (64%) were hired by McGill and Concordia, while these two universities accounted for only 34% of the province’s total hires. The other 94 (37%) professors who graduated in the United States were found in the dozen French-language universities in the province, which in turn represented 67% of total professor hires between 2000 and 2024. It should be noted that of the 94 “American” hires made in French-language universities, 42 were at the Université de Montréal and only 15 were at universities located in the regions.

As with the social sciences, the international hiring pool for French-speaking Quebec universities in the natural sciences is, unsurprisingly, in France. Professors who obtained their doctoral degrees in this country represent a quarter of international hires at French-speaking universities (this proportion increases to a third if those from Belgium and Switzerland are added).

McGill and Concordia universities, on the other hand, are much more closely integrated into the hiring networks of American and English-speaking Canadian universities. Nearly 58% of their professors hired between 2000 and 2024 obtained their doctoral degrees in the United States or English-speaking Canada.

Hiring hierarchies in natural sciences

As in the case of the social sciences, the dynamics of “local” hiring in the disciplines of the natural sciences reveal a linguistically partitioned and highly hierarchical market according to the prestige of the universities and their geographical position.

Thus, between 2000 and 2024, professors with degrees from a French-speaking Quebec university represented only 3.8% of the total hires made by McGill and Concordia universities. Conversely, professors with a doctorate from McGill University alone represented 11% of hires made by French-speaking universities.

During the same period, metropolitan French-speaking universities hired only 2.3% of professors who had obtained their doctoral degree from a regional university. This latter figure raises a real question about the purpose of doctoral training in regional universities.

Indeed, according to the Official Statistical Data Bank on Quebec , their doctoral graduates represented, between 2010 and 2024, nearly 21% of the total number of doctors trained by French-speaking Quebec universities in pure sciences.

An exodus of “brains” to Quebec unlikely

These figures, for both the social sciences and the natural sciences, show that it is illusory to think that the drastic cuts made by the Trump administration in federal research funding will lead to a significant influx of the best American “talent” to Quebec.

Academic job markets are subject to significant inequalities. Their structures have been forged over decades, even centuries, of unequal accumulation of symbolic and material capital in the academic field.

To think that the agents operating in these markets do not take into account their implicit hierarchies, their geographical, linguistic and cultural specificities, is to believe that universities have no national roots and only obey the liberal myth of homogeneous markets where competition is free and perfect.

This passing excitement highlights the fact that some leaders have a limited vision of the mission of their universities, which is far from being limited to puffing out their chests and thinking they are “leaders” in this or that “cutting-edge” field, while current university budgets barely cover current expenses and additional cuts are announced.

It is also disturbing to observe this sudden desire to hastily hire scientists already established abroad, while Quebec graduates struggle to find positions. Perhaps the latter do not live up to the rhetoric of “excellence”?

Author Bios: Mahdi Khelfaoui is Professor at the University of Quebec in Trois-Rivières (UQTR) and Yves Gingras is Professor of History and Sociology of Science at the University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM)