It is time to take human-AI dialogue seriously again. With the release of sophisticated chatbots like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, effective human-AI dialogue has become interesting and accessible to everyone. Even to students writing essays, which has led to some academic concerns.

How will we know if what we read was written by an AI and why is that important? Who are we responding to when we comment on an essay or article? By looking to the philosophical history of dialogue, we can reframe the question to ask how we might use these new chatbots in our learning.

More capable AIs

AI’s connection with dialogue has a history. In 1950 English mathematician Alan Turing proposed an “imitation game” where a judge entered into a typed dialogue with an AI pretending to be human as a way of testing if the AI was intelligent.

So what would today’s AI chatbots have to say about such dialogue? Lex.page is an AI-enabled writing tool that can generate text or answer questions. Here is what the AI built into Lex.page said when I asked it about AI and dialogue:

AI is related to dialogue in a variety of ways. These can be used to create natural, human-like conversations and interactions with users, enabling computers and other devices to understand and respond appropriately to user inputs. It can also be used to analyze and interpret conversation data, helping to improve customer service, detect fraud and more.

The appeal of the Turing Test was that it avoids formally defining intelligence and that it draws on one of the most quintessentially human of interactions, conversation. As the Lex.page AI described it:

In this so-called “Turing Test,” a human would converse with two entities, one of them being a machine, without knowing which one is the machine. If the human cannot tell the difference between the machine and the other entity, then the AI has passed the Turing Test.

For decades human-computer dialogue took the form of a command line where you could boss around an operating system. Examples included Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA which responded like a therapist, asking you what you thought about whatever you mentioned.

What’s changed now is the development of Large Language Models (LLMs) that are trained on billions of pages scraped mostly from the web. These are far more literate and capable of holding a conversation or even generating short essays on topics.

The Turing Test was a great way to see if an AI-driven machine is able to fool humans by impersonating them. In 2018, Google CEO Sundar Pichai unveiled Duplex, a voice assistant, that was able to book a hair appointment without identifying as an AI.

It is not surprising therefore that it was a dialogue with the Language Model for Dialogue Applications (LaMDA) that convinced Google engineer Blake Lemoine that the AI might be sentient and therefore worthy of ethical consideration.

As Lemoine said, “If I didn’t know exactly what it was…I’d think it was a 7-year-old, 8-year-old kid that happens to know physics.” When he took the transcripts to higher-ups they dismissed the evidence and when Lemoine went public with his ethical concerns he was placed on paid leave.

So what next? Perhaps we can look back at how dialogue has been discussed in philosophy.

Dialogue in philosophy

There is a long tradition in philosophy of thinking through difficult topics with dialogue. Dialogue is a paradigm for teaching, inquiry and a genre of writing that can represent enlightened conversation.

In the dialogues of Plato and Xenophon, Socrates is presented as doing philosophy through dialogue. Questioning and reflecting back on questions allowed Plato and Xenophon to both explain the uses of dialogue and present models that we still learn from 2000 years later.

In my book, Defining Dialogue, I document how dialogue is a genre of writing whose popularity waxes and wanes as the culture of inquiry changes. It is also a form of engagement that has been theorized, more recently by scholars like Mikhail Bakhtin.

In Plato and Xenophon’s time, dialogue was a preferred form of philosophical writing. In later periods, works like David Hume’s Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779) were the exception. They written to handle delicate subjects where an author might want to avoid taking a clear position.

In the Phaedrus, Plato contrasts set speeches with passages of dialogue. He shows Socrates as the master of speeches arguing then for the superiority of dialogue. A speech, like written essays, can’t adapt to a listener or reader. Dialogue, on the other hand, engages listeners in a way AI chatbots might also be adapted to do.

And as Lex.page explained:

In Xenophon’s portrayal, Socrates would ask a series of questions to draw out the ideas of his interlocutor, often turning the conversation around to bring out an opposite point of view in order to examine the argument more fully. He would also engage in dialectic, the practice of seeking truth through the exchange of ideas.

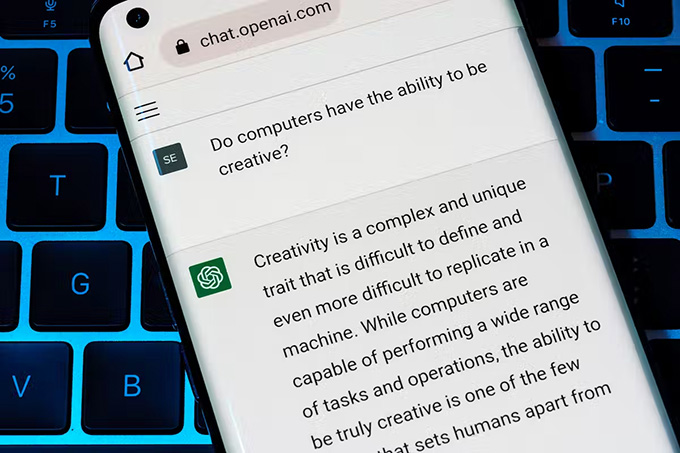

An AI chatbot responds to a question about computers and creativity. (Shutterstock)

Thinking-through dialogue with machines

Now, with the rise of chatbots, dialogue’s time has come around again. I suggest that we can make a virtue of the availability of these chattering machines.

For example, you can engage with the ethics professor I created using Character.AI. Character.AI is a service where you create a fictional character that you and others can then engage in conversation.

Users can question the professor (or other characters) so as to record a dialogue; something they couldn’t do with any old textbook. However, they shouldn’t trust everything the professor says. As the Character.AI site notes, everything the characters say is made up. Perhaps you can get it to admit it isn’t ethical to try to fool us by pretending to be human, something I couldn’t.

In my teaching I ask students to try using these different chatbots to generate dialogues. That raises questions about what a dialogue is supposed to do and how it can be used to convey ideas. It raises questions about how you script an effective dialogue and how to assess it. Students now have reason to reread ancient dialogues to see how they work dramatically.

If we’re worried about plagiarism why not train students to work with AI writing assistants and learn to think through the dialogue? We could teach them to use chatbots to get ideas, to generate alternative approaches to a topic, to research questions and to edit what they get into a coherent whole.

At the same time, we also have to teach our students to be careful and think critically about engaging with AIs and assessing the credibility of what they say.

By thinking through dialogue we could all rediscover the rich history and potential of this form of engagement.

Author Bio: Geoffrey M Rockwell is Professor of Philosophy and Digital Humanities at the University of Alberta