Australian academic Kylie-Moore Gilbert is finally free and back home. The Melbourne university academic was unjustly deprived of her liberties for 804 days for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. She was arbitrarily imprisoned on cooked-up espionage charges while visiting Iran for a conference.

While we are celebrating Moore-Gilbert’s freedom here in Australia, let us not forget we are living in a world where a disturbing pattern of rising and often violent attacks on higher education communities, both academics and students, is taking shape. A harsh fact remains: nobody will face justice for unjustly imprisoning and traumatising Moore-Gilbert.

Academic freedom is under attack

The recently released Free to Think 2020 report of a New York University-based advocacy group for defending academic freedom, Scholars at Risk, shines a light on these attacks on higher education institutions. It reports:

State authorities around the world used detentions, prosecutions, and other coercive legal measures to punish and restrict hundreds of scholars’ and students’ research, teaching, and extramural expression and associations. These actions were frequently carried out under laws or on grounds ostensibly related to national security, terrorism, sedition, and defamation.

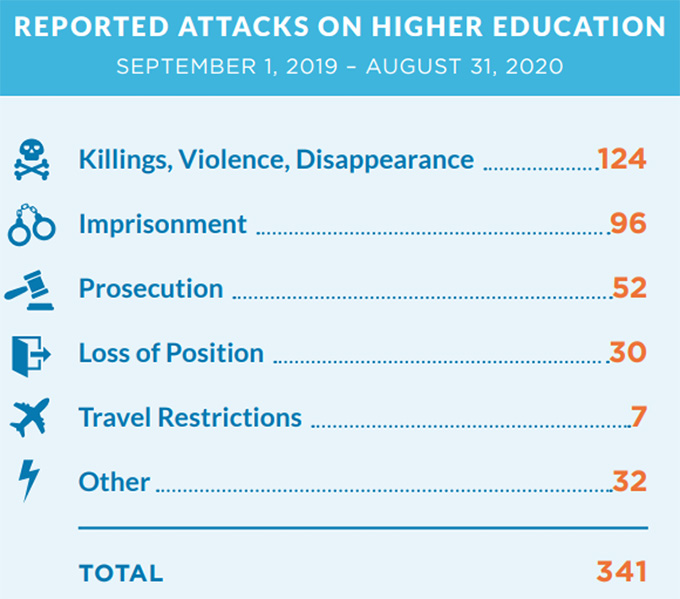

In just one year (September 1 2019 to August 31 2020), Scholars at Risk documented 341 attacks arising from 259 verified incidents in 58 countries. It reports 124 higher education community members (both students and scholars) were killed, faced violent bodily harm or were forcefully disappeared. Another 96 were imprisoned.

Free to Think 2020/Scholars at Risk

Freedom to Think reports covering the past four years (September 1 2016 to August 31 2020) worldwide show 395 higher education community members were killed, faced violent bodily harm or forcefully disappeared. During this period, 393 were sent to jail and 260 were prosecuted for rightfully exercising their academic freedom.

These are just the confirmed figures. Many such cases go unreported or undocumented.

In the past year, the Free to Think report notes that scholars and students in Spain, Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Egypt, Russia and Zimbabwe were arrested and/or imprisoned in connection with explicitly academic work, as well as nonviolent expression and activism.

In Hungary, the Central European University was forced out of the country altogether. In Turkey, Istanbul Sehir University was shut down. And in Romania and Poland calls to cut funding for gender studies and “LGBT ideology” have received strong political backing.

This is the nature of a time when freedom is in retreat. According to a 2019 report by Reporters Without Borders, 76% of the world’s people live in places where the press is not free.

Acknowledging this pattern, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison said after Moore-Gilbert’s release:

[W]e live in an uncertain world and we live in a world where there are regimes that don’t act in relation to people’s liberties and rights and with the freedoms that we enjoy here in Australia and that is just a sad reality of the world which we live in. And Australia has to deal in that world […].

Australia has a role to play

So should Australia be worried about this world where attacks on higher education institutions are on the rise? The simple answer is yes. And Australia should be a strong and active international defender of academic freedom.

The government should spell out its commitment to academic freedom in its foreign policy, research grants, development assistance and travel advice. Australia is a global force; it invests millions of dollars in providing development assistance to many countries where academic freedom is under threat.

Our country has opportunities to directly influence key actors in these countries. Australia offers training, short courses and scholarships to foreign bureaucrats, military professionals, pro-regime academics and security forces of non-democratic countries. Despite their Australian training and experience of our free, law-abiding and democratic society, many of these actors actively suppress academic freedom in their home countries.

Similarly, Australian academics and their research are not isolated from these issues. They study many of these problematic countries, visit them for fieldwork, form cross-country research collaborations and exchange knowledge. Their work contributes to Australian understanding and helps shape foreign policy.

In the wake of the release of Kylie Moore-Gilbert, I hope the Australian higher education community will remain passionate about academic freedom abroad and engage in more research and discussion of the global decline in academic freedom. The pursuit of truth and expansion of knowledge are not confined within geographic boundaries. These issues affect us all.

Author Bio: Mubashar Hasan is an Adjunct Research Fellow, Humanitarian and Development Research Initiative at Western Sydney University