I dont write much about research methods on this blog. That’s not because I’m not interested in research methods – I’ve published three methods texts, after all – but more because I’m pretty sure people who come here mainly want to read about writing. But the two things are not really that easily separated. The way in which you generate, analyse and interpret data, and what and how you write about your results, are linked.

The tangle of writing and analysis are generally an issue if you work with what are usually called qualitative approaches. And that’s often what I do. My preferred mode of research is to generate a hefty amount of wordy material. Even if I have numbers, which these days I often do, I am always more interested in the detail that you get from working with real live people.

Qual researchers get pretty familiar pretty quickly with the difficulties of writing about people who have given up their time to talk with you, who’ve invited you into their space and allowed you to walk away with recordings of their words, feelings, actions and selves. How do you account for this gift fairly and “truthfully”? You see, questions about representation do not stop at anonymity and confidentiality. There are other much more complicated issues related to harm, benefit, and doing justice to and for your participants. And I’m sorry to say that, in my experience, the more research training focuses on analysis as a primarily technical matter, the more many of these tricky ethical-representational-texting issues get left to individual researchers to sort out for themselves.

A step towards dealing ethically with people in text is to use strategies which help you to understand why your participants do what they do, say what they say, behave as they behave. Here is one strategy that might be helpful for you in considering what’s going on for your participants. It’s called empathy mapping.

Empathy mapping can be helpful at any stage of analysis, but it may be particularly useful if you have generated themes and want to put them together in narrative form. The story that you tell, and how you write it, will depend very much on whether you can see your participant as a sense-making person, as well as a set of themes and codes. Using an “empathy-explanatory” approach doesn’t mean you avoid normative judgments, but it does mean that judgment isn’t your first response. Your first move is to comprehend.

Caveat One before I start. This empathy mapping strategy is likely to be most helpful for people using some form of social or cultural analysis, or people who want to bring this disciplinary perspective to their data.

Caveat Two before I go on. It is important to understand that the empathy map is all about interpretation. It is thus always useful to ask yourself, as you do with any interpretation, how your own positioning might stop you seeing and understanding what’s in front of you.

Empathy mapping

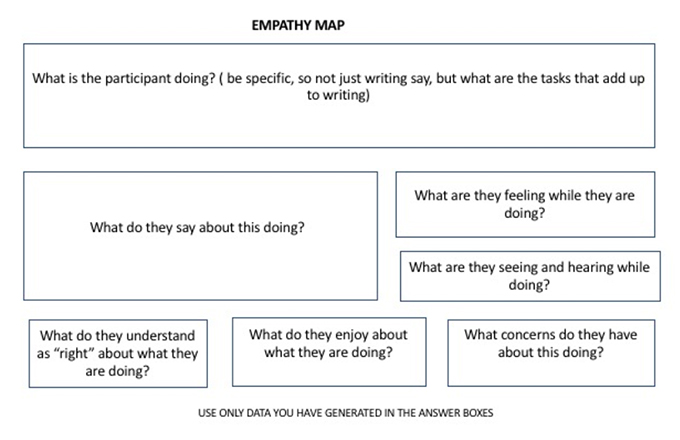

Using the data you have generated – interviews, observations, conversations, artefacts – ask questions that help you focus on the participant’s point of view, experiences and motivations. Use quotations or observation notes as your answers – don’t brainstorm answers to the questions. Your goal is to get down the “stuff”, the data you’ve made during the research. If you can’t answer some of the questions, that’s OK. It’s helpful to know what you don’t know.

Questions:

- What is the participant doing? ( be specific, so dont just for example put “writing”, say what the writing tasks are)

- What do they say about this doing?

- What are they feeling when they are engaged in doing?

- What are they seeing and hearing while doing?

- What do they understand as “right” about what they are doing?

- What do they enjoy about what they are doing?

- What concerns do they have about this doing?

You might like to put these answers into diagrammatic form e.g.

You might see some connections. Mark them in. And please do change these questions and adapt them for your situation and particular research project if these don’t do it for you.

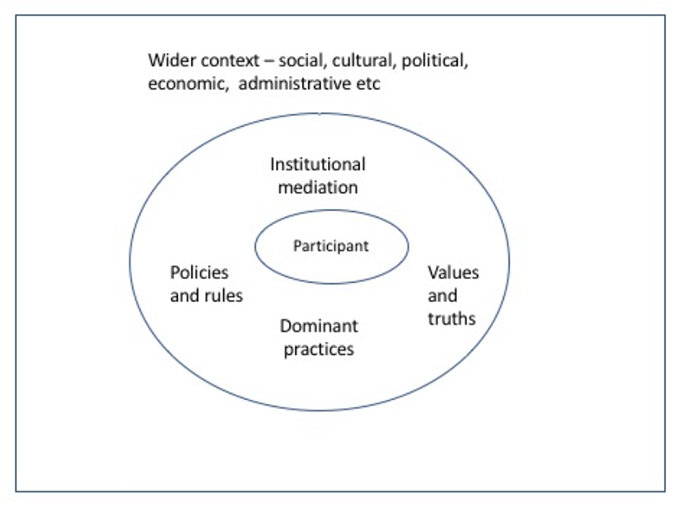

Next ask yourself, what is the context in which this doing occurs? It often helps to think about the doings in two layers – the wider social-cultural context, and then the immediate institutional/organisational context. It’s helpful to specifically ask how wider social and cultural relations are interpreted and made into rules, customs, practices, narratives etc by the institutional/organisational. (Social scientists usually call this mediation).

Once you have elaborated the wider context and the institutional mediating layer you can begin to make more sense of your answers to (1) to (7). You can see how your participant’s actions, feelings, sayings, interactions, relationships etc have been both constrained and enabled by where and how they are positioned. You can also perhaps see how much choice and agency they have, and you can understand the logics of your participant’s actions and words.

At the end of these two moves, you are now much better placed to consider normative questions and any ethical dilemmas that may arise.